One of the byproducts of China’s rigid online censorship is the rich vocabulary collectively invented and adopted by Chinese Internet users: symbols, homonymous, argot, acronyms, and English words and letters have been used in increasingly creative ways to evade Communist Party censors. Now, online software has been developed to do it all automatically.

A program called the “Anti-Harmonizer” (fang hexie qi) has gained attention and popularity among the Chinese Internet citizenry (netizens). “Harmonization” is a common sarcastic reference by Internet users to the Communist Party’s euphemism for suppressing dissent and censoring voices unfavorable to the regime, ostensibly to foster a “harmonious society.”

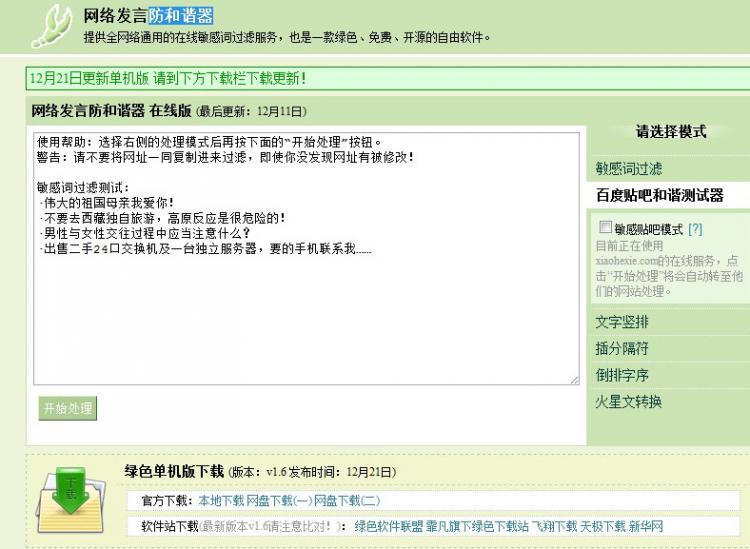

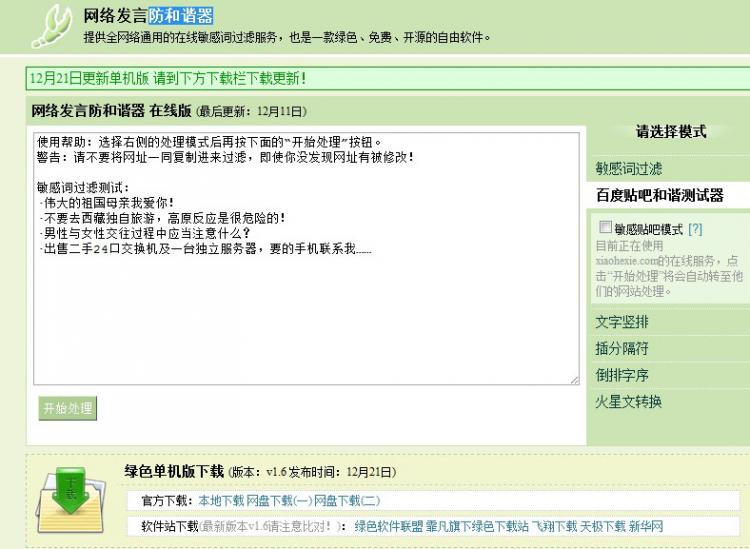

The Anti-Harmonization software, hosted at fanghexie.tk and available for download, is a conversion tool with a battery of options to twist, invert, substitute, and recompose a block of text in ways that the Party’s most zealous censors could never guess. The conversion methods include inserting symbols between censored words or after every word, rearranging the article vertically or backward, or replacing censored words with similar-looking characters and symbols, including English ones.

Some of the English terms blocked on the Chinese Internet include “peace,” which has been censored since the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to jailed dissident Liu Xiaobo, and the innocuous phrase “empty chair,” which fell victim to censorship after the Peace Prize was placed on one because its intended recipient was behind bars.

The vast range of censored language has brought with it the collateral damage of hampering regular, non-subversive communications. One example listed on the fanghexie website shows how the sentence “do not travel alone in Tibet” will be censored because it contains the phrase “Tibet independence” in Chinese.

An explanation of the software says its check list includes more than 9,600 words that are “harmonized” on major blog sites, chat tools, and in the mandatory censorware Green Dam. The list mainly includes pornographic and politically sensitive words.,

The meaning of “politically sensitive” is highly extensible, however. Three phrases recently added to the censorship repertoire are good examples of the kind of things the regime is likely to block. The first is the name of a popular CCTV hostess Wang Xiaoya, who is rumored to be cavorting with a senior Party official; the second is “three Fuzhou netizens,” which refers to three bloggers arrested for posting information about a 25-year-old girl who was allegedly killed after being gang raped in a police-backed Karaoke club; the third is Yuan Tengfei, a Beijing high school history teacher who is widely known for his engrossing lectures on Chinese history and sharp criticism of Mao.

The regime’s own news items can sometimes fall victim to censorship. A Radio Free Asia reporter used the program to check an article about Premier Wen Jiabao meeting the Pakistan president, news that was published in Party media. The program spotted 28 sensitive phrases in the 460-word piece. Previous research has shown that even the names of top leaders and their political slogans can be censored.

“If you feed the Chinese Constitution into the system, more than 50 percent of it will be censored,” said Zhang Tianliang, a political commentator. “It’s pathetic. With an anti-harmonizer, the Chinese people can express themselves more freely.”

In a disclaimer posted on the website the developer, who calls himself “Zilaishui,” meaning “tap water,” said the program was meant only to prevent such friendly fire. “This software…has never encouraged users to use it for illegal purposes,” the statement says. “…We will cooperate with the police to identify illegal users.”

Whether by design or no, the program will probably be most useful to activists and dissidents, who are most vigorously censored.

At a 2005 hearing, Harvard Law School professor John Palfrey told the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission that China has “the most extensive and effective legal and technological system filtering Internet content, censorship and surveillance available in the world today.” Information about Falun Gong, the Tiananmen massacre, and Tibet and Taiwan independence are the most filtered topics, said Palfrey, faculty co-director of Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society.

Palfrey’s research also indicated that though the regime uses anti-pornography as a colorable explanation for online censorship, less than 10 percent of the sites relating to pornography were blocked—compared to the 90 percent filter rate against The Nine Commentaries of the Communist Party, an in-depth critique of the Chinese Communist Party published by this newspaper.

A program called the “Anti-Harmonizer” (fang hexie qi) has gained attention and popularity among the Chinese Internet citizenry (netizens). “Harmonization” is a common sarcastic reference by Internet users to the Communist Party’s euphemism for suppressing dissent and censoring voices unfavorable to the regime, ostensibly to foster a “harmonious society.”

The Anti-Harmonization software, hosted at fanghexie.tk and available for download, is a conversion tool with a battery of options to twist, invert, substitute, and recompose a block of text in ways that the Party’s most zealous censors could never guess. The conversion methods include inserting symbols between censored words or after every word, rearranging the article vertically or backward, or replacing censored words with similar-looking characters and symbols, including English ones.

Some of the English terms blocked on the Chinese Internet include “peace,” which has been censored since the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to jailed dissident Liu Xiaobo, and the innocuous phrase “empty chair,” which fell victim to censorship after the Peace Prize was placed on one because its intended recipient was behind bars.

The vast range of censored language has brought with it the collateral damage of hampering regular, non-subversive communications. One example listed on the fanghexie website shows how the sentence “do not travel alone in Tibet” will be censored because it contains the phrase “Tibet independence” in Chinese.

An explanation of the software says its check list includes more than 9,600 words that are “harmonized” on major blog sites, chat tools, and in the mandatory censorware Green Dam. The list mainly includes pornographic and politically sensitive words.,

The meaning of “politically sensitive” is highly extensible, however. Three phrases recently added to the censorship repertoire are good examples of the kind of things the regime is likely to block. The first is the name of a popular CCTV hostess Wang Xiaoya, who is rumored to be cavorting with a senior Party official; the second is “three Fuzhou netizens,” which refers to three bloggers arrested for posting information about a 25-year-old girl who was allegedly killed after being gang raped in a police-backed Karaoke club; the third is Yuan Tengfei, a Beijing high school history teacher who is widely known for his engrossing lectures on Chinese history and sharp criticism of Mao.

The regime’s own news items can sometimes fall victim to censorship. A Radio Free Asia reporter used the program to check an article about Premier Wen Jiabao meeting the Pakistan president, news that was published in Party media. The program spotted 28 sensitive phrases in the 460-word piece. Previous research has shown that even the names of top leaders and their political slogans can be censored.

“If you feed the Chinese Constitution into the system, more than 50 percent of it will be censored,” said Zhang Tianliang, a political commentator. “It’s pathetic. With an anti-harmonizer, the Chinese people can express themselves more freely.”

In a disclaimer posted on the website the developer, who calls himself “Zilaishui,” meaning “tap water,” said the program was meant only to prevent such friendly fire. “This software…has never encouraged users to use it for illegal purposes,” the statement says. “…We will cooperate with the police to identify illegal users.”

Whether by design or no, the program will probably be most useful to activists and dissidents, who are most vigorously censored.

At a 2005 hearing, Harvard Law School professor John Palfrey told the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission that China has “the most extensive and effective legal and technological system filtering Internet content, censorship and surveillance available in the world today.” Information about Falun Gong, the Tiananmen massacre, and Tibet and Taiwan independence are the most filtered topics, said Palfrey, faculty co-director of Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society.

Palfrey’s research also indicated that though the regime uses anti-pornography as a colorable explanation for online censorship, less than 10 percent of the sites relating to pornography were blocked—compared to the 90 percent filter rate against The Nine Commentaries of the Communist Party, an in-depth critique of the Chinese Communist Party published by this newspaper.