On Dec. 31, 2011, Zhong Jinhua, a former Chinese judge and successful attorney, suddenly became an enemy of the state.

“If the ban on political parties and limits on the press are not removed within five years … the people and intellectuals won’t stand for it,” he wrote on his Sina Weibo microblog. “I'll be the first to announce my resignation from the Chinese Communist Party, and organize democratic political parties to overthrow the dictatorship!”

Zhong’s sizable Weibo fanbase shared the comment thousands of times within hours, and he received a flood of praise before the post was purged.

The Party’s mechanisms of control and suppression kicked in immediately: Security agents began calling his cellphone, he was ordered back to Shanghai, and the head of his law firm began thinking up ways to fire him. In the end he managed to keep his job, but the damage had been done: Zhong was now an “anti-Party element.”

Zhong Jinhua, a judge who became a lawyer and then an activist, was a relative latecomer to the “weiquan,” or rights defense movement in China, when he began his activism in earnest. But the story of his legal work on both sides on the bench, and then how the Party came down hard and forced him into exile, affords a glimpse of the frontlines of the struggle for Chinese to realize the rule of law and the regime’s all-out efforts to shut them down.

‘Justice Is in My Genes’

If China was to do business with the world, the former Party patriarch Deng Xiaoping reasoned in the early 1980s, the regime needed a legal system that would instill confidence in foreign investors. Law schools began taking in eager young Chinese and minting thousands of new lawyers and judges each year.

In 1990, a 20-year-old Zhong began his legal training at Minzu University of China in Beijing. He graduated in 1994 and found a job as a clerk in the criminal trial division of the Wenzhou Intermediate People’s Court, in the coastal province of Zhejiang. He was soon made chief judge, a position he retained until July 2008.

“Justice is in my genes,” Zhong said in a recent interview with Epoch Times in New York City. But he began finding it increasingly difficult to balance being a clean judge—he was often beset with gifts of cigarettes or expensive wines, all of which he curtly returned—and bringing home adequate income for the family.

“Practically all government officials will be bribed at some point in their careers,” Zhong said. “The irresponsible and corrupt abuse their position.” Zhong said he never did so, instead explaining to the parties that his decisions were based solely on merit.

After he joined the Shanghai branch of the Yingke Law Firm, the second-largest in China, he felt he would finally be able to start speaking his mind, especially on questions of justice.

The first spark came with the Beihai case in Guangxi in southern China, late 2011, when lawyers defending five people accused of murder—on what the lawyers said was woefully insufficient evidence—were themselves prosecuted and detained by the authorities. The case summed up the essence of politics and law in China, Zhong says: “Criminal cases become political cases when they get a lot of attention.”

Zhong had been keenly following human rights issues since 2009 and was increasingly disillusioned with the injustices perpetuated under communist rule, and frustrated with the Party’s inability to reform itself. Turning over the Beihai case and other instances of unfairness in his head, Zhong felt a surge of unhappiness and anger. In a moment of rashness, he broadcast his desire to quit the Party on the eve of 2012.

Controlling an ‘Anti-Party Element’

When Zhong wrote the fateful Weibo post, his education in the political sensitivities of the Communist Party really began.

He was in Inner Mongolia on a case at the time, and within hours began receiving frantic calls from the Shanghai domestic security department, the Shanghai justice bureau, and his own law firm. He was told to return immediately. Fearing detention, he slipped on a plane to his native Wenzhou, where he lay low for a week, renting hotel rooms using ID cards borrowed from friends. He only returned to Shanghai when he got assurance that he wouldn’t be arrested outright.

The first guest he entertained in the firm’s conference room was the Party secretary of the Bureau of Justice of Shanghai’s Zhabei District, who brought an entourage of local Party toughs. “Lawyer Zhong, today I represent the Shanghai Zhabei Justice Bureau Party Organization,” the man announced in a slow, stentorian voice, Zhong recalled. “They were acting serious and formal, so to break the tension, I would crack jokes and get them to loosen up.”

Zhong’s attempt to introduce some levity didn’t change the seriousness of the situation. He was told that unless he signed a confession and apology, he would be seen as an “anti-Party element” and face “serious consequences.” He was pounded with questions about who had “instigated him” to write the note and whether there were any “outside forces” behind the scenes.

The cadres, speaking at a later interrogation session, seemed particularly exercised about the fact that, within hours, his Weibo outburst had been reported by New Tang Dynasty Television, a New York-based Chinese language broadcaster. NTD is part of the same media group as this newspaper.

Zhong escaped the encounter without making any concessions, but he was now under close watch. His friend at the firm—the deputy of its Party cell—was made his minder, responsible for monitoring his meetings and online activities, and reminding him constantly whenever he made “sensitive” posts on Weibo or WeChat.

For months he was subject to increasingly insistent urging to leave the firm because of the trouble he was bringing. Even many of the colleagues who had headed off his earlier, imminent dismissal were now exhorting him to leave. “Go back to Wenzhou,” they'd say, Zhong recalled. “There’s no place for you in Shanghai.”

Zhong wasn’t run out of town, but he did quit, the upshot of a negotiated blackmail by his own firm, which planned to effectively disbar him otherwise. He was allowed to keep his law license as long as he moved on.

This period was characterized by tight surveillance: regular computer hacking, overt monitoring by the security guards working at his own apartment complex, intrusive visits by “household residency” inspectors, and random encounters with officious women in the Neighborhood Committee—China’s block monitors.

For the next two years, Zhong labored under both stressful surveillance and the psychological burden of being prevented from human rights work. His new law firm, Jingheng, had been directly instructed by Party judicial officials that he was not to be allowed near “sensitive” cases.

For two years, Zhong handled vanilla commercial and criminal matters, at one point successfully defending a young woman wrongly accused of transporting drugs. The surveillance slowly relaxed.

“But I couldn’t take it,” he said. “I felt like I needed to be concerned with and involved in resolving cases of injustices in society.”

He added that his reaction was simply to act against injustice. “When people are being unfairly treated, it’s only natural to want to help. It’s that simple.”

Zhong was about to start his own law firm in 2014 to regain autonomy in the type of legal cases he could do, when he received an opportune offer to be a partner at the Ganus Law Office in Shanghai.

“They didn’t do a thorough background check,” Zhong said with a grin. “So they let me take on human rights cases.”

‘Defending Rights’

Zhong Jinhua was a latecomer to the human rights scene—and so he missed some of the signal developments while he was turning down bribes.

These include the national uproar caused by migrant worker Sun Zhigang’s abuse and death in 2003. Three legal scholars, Teng Biao, Xu Zhiyong, and Yu Jiang, submitted a legal petition to the regime’s faux legislature to change the custody and repatriation system—a means of arbitrary detention used by police—and while they didn’t receive an official response to their petition, the abusive system was eventually abolished.

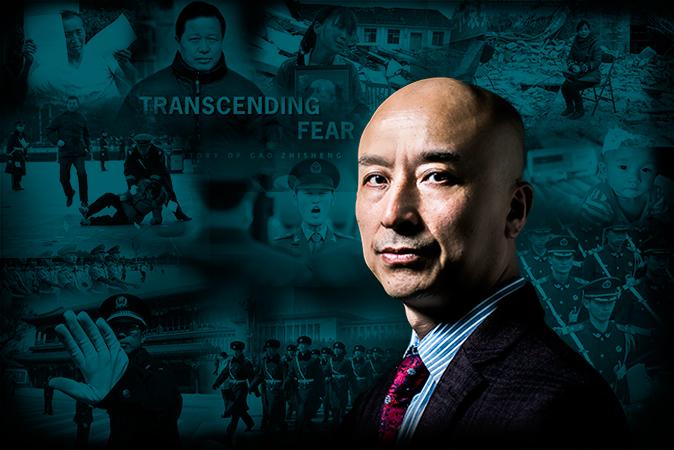

Zhong also missed the significant stir that Gao Zhisheng, a rights lawyer, created in 2005 and 2006 when he broke the Party’s taboo on providing legal aid to practitioners of Falun Gong, a persecuted spiritual discipline. In three open letters to the Party’s top leaders, Gao called on the regime to end the suppression of Falun Gong, and later publicly announced his resignation from the Communist Party. He was abducted in 2006, was severely tortured on at least three occasions, and has spent most of the past decade in some form of detention.

But when Weibo—China’s version of Twitter—came along in 2009, Zhong Jinhua suddenly had a way to learn about rights abuses across the country and reach out to defenders of justice, at any time.

Zhong said that the ability to connect with the weiquan (rights defense) community was the “most important influence” in his eventually becoming a human rights lawyer. “They were all doing righteous things, so I decided to join them.”

“Social media had a significant effect on rights lawyers and their ability to connect with one another: All the most active lawyers knew one another and were connected on WeChat,” said Teng Biao, now a fellow human rights lawyer in exile, and a visiting fellow with the U.S.–Asia Law Institute at New York University (NYU).

Speaking to Epoch Times over the telephone, Teng added: “Weibo, a bigger platform, was a way for other like-minded lawyers to know what we were doing and express support. It really allowed us to get an audience.”

According to an interview Teng gave with the New York Review of Books in 2014, there were about 20 or 30 weiquan lawyers when the movement started in 2003. In 2014, there were 200 very active human rights lawyers, and 600 or 700 lawyers who would defend human rights cases.

The core concept of rights defense activism is to establish the rule of law in China. The Party is not bound to the Chinese constitution, and it frequently operates outside the law.

To force the Party to be accountable to its own laws, the rights defense lawyers and activists use the letter of the Chinese law to defend the rights of Chinese citizens. In a country ruled by law, this is the basis of all legal work. In China, however, an attempt to apply the law to areas that have been declared political—most prominently, those involving the human rights of citizens—is considered deeply subversive, because it undermines the regime’s monopoly on power.

Since the Sun Zhigang incident in 2003, weiquan attorneys have challenged the regime on multiple fronts. Among other issues, they have taken cases involving grassroots democracy activists, political persecution, religious persecution, the one-child policy, freedom of expression, forced evictions, food safety, policy brutality, the re-education through labor system, and wrongful convictions.

Getting Involved

At Ganus, his third law firm, Zhong finally had the opportunity to roll up his sleeves.

“When lawyers are arrested for no good reason, I get very angry,” he said. So when Zhang Keke was hauled out of a court while he was midway through his defense statement in December 2014, Zhong stirred into action. Zhong and Shandong lawyer Feng Yanqiang braved the heavy snow in the province of Jilin in northeastern China where the incident took place and filed legal complaints against Jilin’s public security bureau, the local court, and the lawyer’s association.

The case was highly sensitive in China because Zhang was defending Falun Gong practitioners. As Zhang was giving his defense in court, the judge gave the signal to members of the domestic security bureau to march down and drag the lawyer out of the courtroom.

The local prosecuting department accepted the complaint but threw it out on the basis that Zhong and Feng didn’t have enough evidence to sue. “They’re all one gang,” Zhong said.

From the snowy northeast, Zhong traveled to Shenzhen in subtropical Guangdong Province to help local rights lawyer Fan Biaowen. Fan had represented labor workers, Tiananmen Square activists, and persecuted Christians. Shenzhen authorities were pressuring Fan’s law firm to terminate his contract, and there seemed to be a conspiracy to ensure that he wouldn’t work in law in Shenzhen again.

A week of interviewing made clear to Zhong that local Party authorities were behind it, using extralegal means to stop the lawyer from representing clients who had been designated, again through an extralegal process, politically sensitive.

Shanghai judicial authorities were furious that Zhong had gone back to “sensitive” cases. They warned him to “pay attention to the impact of your actions” or there would be “serious consequences.” The director and partners at Ganus were also harassed.

Crackdown and New Home

Zhong ignored the threats until the Chinese regime launched a massive crackdown on rights lawyers across the country in July 2015.

The rights defense lawyers are like the Tank Man with a law degree. They put themselves directly in the path of regime suppression, armed only with their courage and their principles.

Prominent rights attorneys like Li Heping, Teng Biao, Tang Jitian, and the blind, self-taught lawyer Chen Guangcheng stood up for those disenfranchised by the Party—and were mercilessly steamrolled by the Party’s security apparatus.

For defending Christians, Li Heping was black-bagged, stripped, beaten, and shocked with electric batons in a detention facility in 2007. In 2011, state security officers also hooded Teng Biao, beat him up, and made him wear handcuffs for 24 hours a day for 36 days during a 70-day detention.

Tang Jitian and three other lawyers were investigating an extralegal detention facility used to hold and torture Falun Gong practitioners in the northeastern region of Jiansanjiang in 2014 when they were themselves arrested and subjected to near medieval torture. Police once tied Tang to an iron chair and hit him over the head with a plastic water bottle until he nearly lost consciousness; on another occasion, they hooded and handcuffed Tang’s arms behind his back, suspended him by his wrists, and pummeled him.

Not even the handicapped were safe—in 2011, about 80 men forced their way into the home of Chen Guangcheng, a defender of women’s rights and victims of the regime’s birth control campaign, to assault and torture the blind lawyer and his wife for over two hours.

The July 2015 crackdown, however, was the most concerted action by the Party’s security forces to eliminate the growing constituency of rights defenders, and it included hundreds of coordinated arrests in the dead of night around the country. About 250 lawyers and rights activists were targeted to date, and 17 were formally arrested, according to Amnesty International.

Fearing that he too would be bundled off, Zhong, desperate, announced on WeChat that he would respond with force to any attempts to break into his home. In the end, he was merely called in and told to keep quiet.

Fearing for his family—a wife and two young children—Zhong made plans to leave for the United States. At the airport in Shanghai as they were to leave for Dallas, he was held up by dozens of public security agents for nearly three hours and allowed to board the plane just as it was about to leave.

Zhong now lives in New Jersey with his wife, 9-year-old daughter, and 2-year-old son. He has been offered a year-long position as a visiting scholar at NYU facilitated by Jerome A. Cohen, the director of the U.S.–Asia Law Institute and law professor at NYU.

“We like to bring in a mix of people from different backgrounds,” said Cohen after a recent luncheon at NYU. “Zhong Jinhua is an intelligent lawyer.”

Presently, the weiquan movement in China is “hurt very badly” by the arrest or questioning of hundreds of rights lawyers, Cohen said.

“It’s very bad for China’s reputation in the world, and it’s very bad for human rights lawyers in China and their clients,” he added. “It’s not a happy time.”

Matthew Robertson contributed to this report.