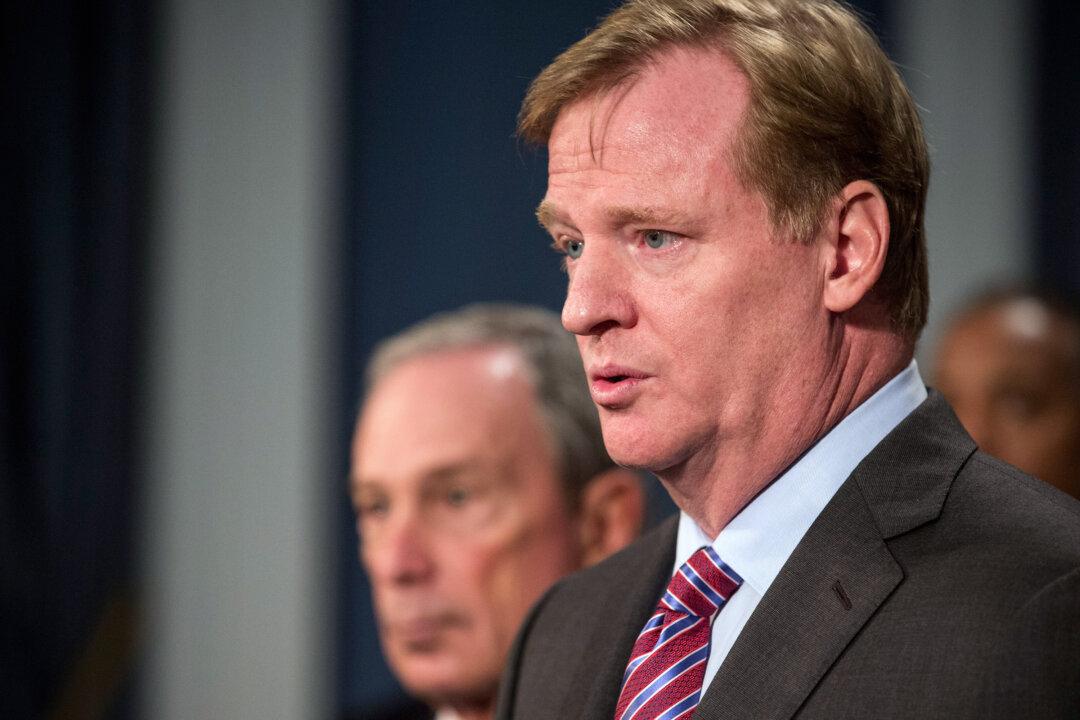

General Motors Corp. Chairman Rick Wagoner looked weary last week in Washington, as he and fellow “Big Three” executives met with Congress over federal funding to rescue the U.S. auto industry, and in turn, Michigan’s economy.

This week, word out of Washington—and among GM investors—is that stakeholders are asking for a head over the auto industry’s near-collapse, and it may just be Wagoner’s. And this columnist believes that if that’s what it takes to save a million people from the unemployment lines and take a chance at revitalizing Detroit’s economy, Wagoner may just take it. But don’t blame him for Detroit’s woes.

G. Richard Wagoner Jr. arrived in Detroit as an outsider. Growing up in Virginia and Harvard-educated, the bright and energetic Wagoner began his GM careers in the 1970s at GM’s treasurer’s office in New York City.

In 1992, Wagoner rose to the position of Chief Financial Officer. He assumed a multitude of roles until 2000, when Wagoner, then a young 47 year old, was elected by the board to become the firm’s president and chief executive officer, succeeding the legendary John “Jack” F. Smith Jr. at the helm of the most iconic manufacturing firm in the United States.

Wagoner became CEO at GM at a time when the company reaped enormous profits from popular pickup trucks and SUVs. GM’s difficult years of the early 1990s were a distant memory, and the efforts of Wagoner and Smith had helped the company become a strong competitor to the Japanese.

Aggressive cost-cutting, payroll cuts, and factory overhauls improved efficiency and productivity at GM’s factories, and increased quality and reliability of its vehicles, a long stigma of American-made cars dating back to the 80s. GM solidified its lead over rivals Ford, Chrysler, and Toyota.

Although GM was making profits in the early 2000s, Wagoner was well aware of its Achilles’ heel—too much legacy burden.

He knew that cheap gas prices, a booming economy, and strong sales of high-margin SUVs deflected attention away from GM’s deeper issues. But GM’s problems could surface quickly if the economy turned sour.

GM dished out generous health and retirement benefit packages decades ago to appease the United Auto Workers union. Due to a particularly onerous contract signed in 1990, GM agreed to pay former employees 70 percent of their annual salaries for years after leaving the company. For every car built, thousands of dollars went toward paying for health and pension benefits to retired and laid-off employees.

And keep in mind that today’s GM is much smaller than the one that ran the auto industry decades ago—it must support a far greater retirement base than it could afford.

“We have a huge fixed-cost base. It’s 30 years of downsizing and 30 years of increased health-care costs. It puts a premium on us running this business to generate cash,” Wagoner said in a 2003 interview with BusinessWeek (BW). Essentially, Wagoner was faced with fixing 30 years of mismanagement at GM.

The truth is, he arrived at the scene after most of GM’s poor management decisions have already been made. GM only pays its current workers a little more than Toyota, Nissan, and Honda pay their non-unionized employees, but legacy overhead expense costs the company an estimated additional $30-$40 per hour per employee.

The choice to go “all in” with SUVs and pickup trucks was also made prior to Wagoner’s appointment. In 2002, an estimated 90 percent of GM’s net profit came from SUVs and pickup trucks. At the time, few could foresee that demand for larger vehicles would drop off as precipitously as it has. Even Toyota and Nissan subsequently introduced heavy SUVs and pickups to boost competition in the field.

After all, Wagoner is not a Detroit auto expert. He let his executives make product decisions, according to reports. “Rick acts more like a coach than a boss,” says David E. Cole, director of the Center for Automotive Research (CAR) in Ann Arbor, Mich. in the BW interview.

Wagoner appointed Robert A. Lutz, an auto industry veteran who previously worked at BMW, Ford, and Chrysler, as GM’s Vice Chairman of Global Product Development. Lutz oversaw the development of popular Saturn Sky and Pontiac Solstice compact sports cars.

Turning around a company—especially one as old and bureaucratic as GM—will not happen overnight, and the pieces for a turnaround seem to be there. Wagoner began as his restructuring process years ago, but unfortunately, time expired on him and his company. As the Wall Street banks can attest, the current financial storm waits for no one.

Back in Washington, lawmakers are pointing a finger at Detroit, inferring that any bailout must accompany drastic business changes at the top, which could mean replacing the current executives.

“You’ve got to consider new leadership,” Sen. Chris Dodd (D-Conn.) said on CBS’s “Face the Nation.” GM’s Wagoner “has to move on,” he asserted.

If Wagoner is gone and GM survives because of a federal bailout, the new CEO would be lauded as both a hero and a visionary. It’s a shame Wagoner never got his chance.