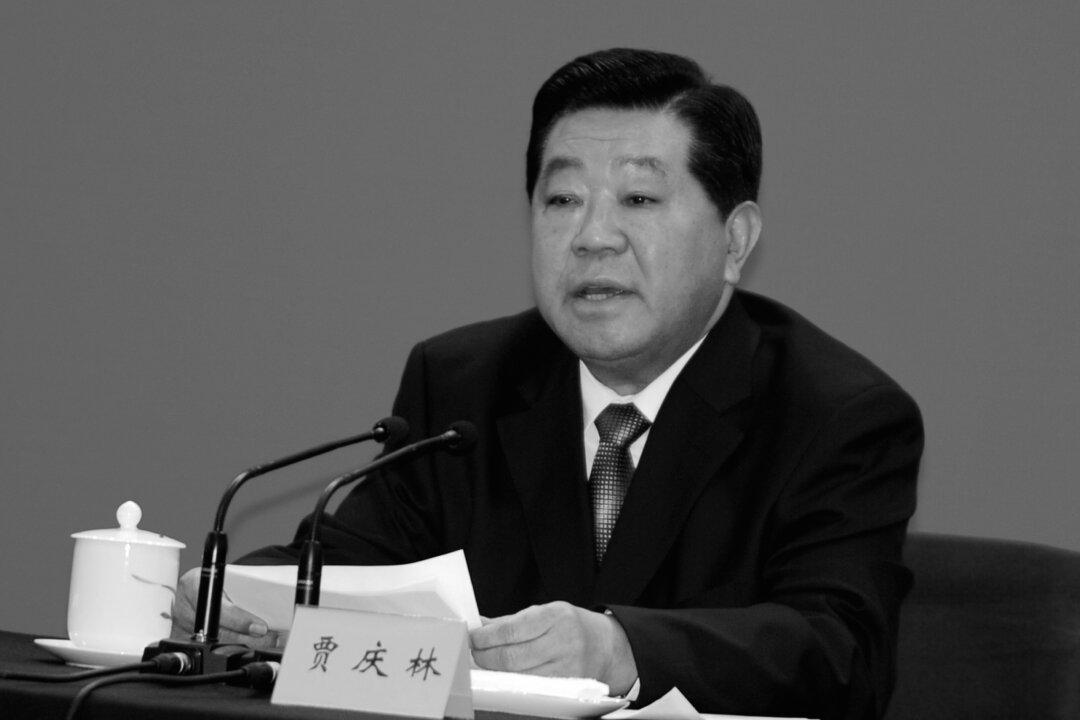

Rumors hit the Chinese Internet last week that Jia Qinglin, the former head of a top-level Communist Party advisory committee and a former member of the Politburo Standing Committee was detained by the authorities.

The claim of Jia’s detention was propagated by Cheng Lingxu, a senior journalist and columnist, and the president of the real estate information website Xiafun.com.

Cheng posted to both his Sina Weibo and Wechat accounts, two popular social media tools, on July 11: “According to a reliable source, 100 percent accurate, former chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Jia QingL was detained in SH prison in Hohhot City last night. Over 500 soldiers were dispatched from the 38th Army of the People’s Liberation Army.” Hohhot is the capital of the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region in North China. Cheng used the letter “L” when writing Jia Qinglin’s name, to avoid his post being censored in China. The reference to a “SH prison” was not clear.

Cheng added: “Friends who have purchased real estate for the Jia family should be careful.” Jia’s ex-wife and son in-law were reported to have been involved in a number of high-profile real estate investments, including an ostentatious mansion in Beijing. “There’s a saying about the ‘Jia system’ in the industry, because of the Jia family’s involvement in real estate,” Cheng wrote in another Weibo post. “A lot of developers and real estate projects are in the Jia family’s shadow.”

The authorities took swift action to crush the rumor. Not only was Cheng’s post deleted, but his entire account—an established “verified” presence—on Weibo and the Tencent microblog disappeared entirely on July 14.

Subsequent to Cheng’s remarks, other users claimed their own inside knowledge of Jia’s arrest, though the veracity of their claims was even less clear than that of Cheng’s.

He Qinglian, a well known Chinese author and political analyst, published a commentary on the affair in Voice of America Chinese, saying that the rumor seemed credible. “As a successful man, Cheng certainly knows what topics are taboo in China. There must be a reason for him to release such information. It’s not that he’s sitting around with nothing to do, and decides he'd like to get a taste of what it’s like jail.”

If the rumor of Jia’s detention is true, it would be yet another “tiger”—the Chinese term regularly used to refer to corrupt top-level officials—that Party leader Xi Jinping has taken down. And like many of the other tigers to be hunted down in the current purge, Jia has extensive and long-running ties with former paramount leader of China Jiang Zemin.

Jia and Jiang worked together at the First Machinery Industry Department through 1960s and 1970s. In the 1980s and 1990s Jia served as a high-level official in the southeastern coastal province of Fujian for over a decade. After Jiang became Chairman of the People’s Republic of China in 1993, Jia was in 1996 promoted to be the mayor of Beijing. In 1997, he was made a member of the Politburo, the powerful Party organ from which the Standing Committee, which rules China, is drawn.

Jia’s path to power was not all smooth. A massive smuggling corruption case, around the Xiamen Yuanhua Group, revealed in 1999, was a crisis point in Jia’s political career. Lai Changxing, the founder of Yuanhua smuggling racket, who became China’s most wanted criminal after he fled to Canada until being repatriated in 2011, once told a Hong Kong reporter that he enjoyed close ties with Jia Qinglin.

Rumor at the time also implicated Jia’s wife, Lin Youfang, in Lai’s smuggling business.

Official Chinese news reports say that the Yuanhua syndicate’s activities reached epic proportions: the group smuggled refined oil, vegetable oil, cars, cigarettes, and far more, with a total worth of roughly 53 billion yuan (approximately US$6.4 billion), and evasions of customs duties of up to 27 billion yuan, beginning in 1996. Lai had paid off the People’s Liberation Army to ensure the security of his shipping lines.

By 2002, 14 people, including officials, had been executed in relation to the case, while 300 provincial officials were put on trial, according to the South China Morning Post.

But Jia, with the help of his political patron Jiang Zemin, avoided all fallout from the case. Not only that, shortly afterwards, in 2003, he was promoted to become chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a Party-run organization that is supposed to provide advice to the Party and also co-opt non-Party social elites.

Jia’s career path may give some indication as to why Jiang Zemin acted to protect and promote him. Most saliently, he was an enthusiastic implementer of the persecution of the Falun Gong spiritual group, since 1999 Jiang’s personal political crusade, after he saw the burgeoning number of Falun Gong practitioners, and the group’s traditional spiritual tenets, as an ideological challenge to the regime. After Jiang initiated the violent persecution, Jia, as Party chief of Beijing from 1999 to 2002, ordered a series of detentions, arrests, and torture of Falun Gong practitioners in the city became widespread.

An immolation incident on Tiananmen Square in 2001, widely thought to be an elaborate hoax used by the government’s propaganda apparatus to defame the practice, also took place under Jia’s watch. For his role in the anti-Falun Gong campaign, Jia has been sued by overseas Falun Gong adherents in courts in Austria, Spain, and the Netherlands for “genocide, the crime of torture, and crimes against humanity,” during his visits to those countries, according to Minghui.org, a Falun Gong website.