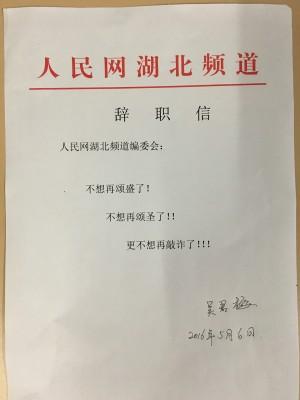

SYDNEY—Unpublished investigations of corruption in China by state media have been used to blackmail the targets of the investigations, according to a journalist with People’s Net, the online version of the broadsheet People’s Daily, who tendered her resignation earlier this month.

When she arrived for a holiday in February, Wu Junmei, the former reporter, reconfirmed everything she had been pondering in China. A week after arriving, she quit the Chinese Communist Party. A few months later, she resigned from her job, and seems unlikely to return to China.

In an exclusive interview with Epoch Times, Wu described her career trajectory, discussed the illicit dealings of People’s Net, and explained what influenced her decision to sever ties with her employer, and the regime.

Dark Dealings

Journalists in the Chinese Communist Party’s media mouthpiece organizations have long been required, besides the usual propaganda work, to engage in investigating malpractices and abuse of power in industry, government, and society. But unlike regular media outlets, this work doesn’t always get published.

For years, such reports were packaged as “internal reference” materials, to be distributed only among the Party elite. But more recently, they’ve come to be used for another favored activity among officials: making money.

It’s this practice that Wu found so unjust and frustrating.

Wu used to work with a provincial television broadcaster before moving to the People’s Net branch in Hebei Province in 2012. She had spent most of her time in the public opinion office, investigating complaints from people living along the Yangtze River about companies polluting China’s longest waterway.

She soon learned, however, that the regime’s mouthpiece was not on the side of the people.

“A normal media would report the facts, and then criticize and condemn the phenomenon it had uncovered, or even go to the related authorities to get them to look after the interests of the people,” Wu said. “But People’s Net doesn’t do this.”

Instead, People’s Net would use the interview recordings and photographs Wu gathered as proof that polluting companies were engaging in illegal operations, and then go to blackmail the companies.

“They would cut deals with the companies and make illicit profits,” she said. Observing these transactions caused Wu to feel “deeply pained and uncomfortable” over the past two years.

Disgusted with the work she was being made to do, Wu turned to religion for solace. Once her bosses found out, however, she was chastised for having a faith other than Marxism.

Faith

Depressed with her job, Wu reached out to a house church at the end of 2014, and for a time found spiritual comfort in Christianity.

However, the Party leaders at People’s Net learned of her newfound faith after she performed in a Christmas Day program in 2015, and sat her down to remind her about the Party’s only truly accepted dogma.

“Because we are mouthpiece of the Party, you are only allowed to hold the Marxist view on journalism. We are doing political work here, and you cannot have any other faith,” a Party leader told Wu. Local state security officers payed her a visit.

The televised forced confession of Zhang Kai, a Christian Chinese human rights lawyer renowned for defending persecuted Christians and other disenfranchised groups, also struck a nerve.

“I was especially angry because I am a Christian,” Wu said. She had caught the confession during a stopover in Guangzhou Province before boarding a flight to Australia, where her son is studying.

“Look at how I, a mere worker at the state mouthpiece, was treated” she said. “I trembled in fear just thinking about what they must’ve have done to Zhang Hai; I’m aware of what he was subject to in detention.”

Renouncing the Party

Wu finally made up her mind to resign from her job and renounce her Party membership, after reading uncensored information in Australia this February.

Doing a Google search, Wu stumbled across a torrent of stories and information about the Tiananmen Square Massacre and the persecution of Falun Gong, a traditional Chinese spiritual discipline, among a range of other human rights abuses in China.

Later, she found The Nine Commentaries of the Communist Party, a nine-part editorial series published by this newspaper in 2004.

“When I first read the series, I had a hard time accepting it,” Wu said. “Those in the news business on the mainland presumed that Falun Gong was criticizing the Chinese Communist Party because Falun Gong hadn’t been treated well by the Party.” The Nine Commentaries is often distributed by Falun Gong practitioners in China, in paper and CD-ROM form, to raise awareness about the historical and contemporary crimes of the Communist Party.

“After reading the Nine Commentaries from cover to cover, however, I really think you can describe it as an X-ray of the Party—its analysis of the Party is just so thorough,” Wu said.