The winter solstice occupies an important place in the pantheon of traditional Chinese festivities. Known in Mandarin as Dongzhi, the shortest day of the year is seen as its turning point: from here on out, the days become ever brighter. The darkness of Yin slowly gives way to the light, or Yang, completing one leg in the endless cycle of time.

Ancient Chinese divided the year into 24 solar terms, usually of 15 days each that mark the change of climate and seasonal transitions. Their functions are reflected in the Chinese imperial calendar and in the timing of various festivities and rituals, including those held on Dongzhi.

Falling on Dec. 21 this year, Dongzhi has had an important place in Chinese tradition for thousands of years. From the Shang and Zhou dynasties to the Qin Dynasty (221 B.C.–A.D. 206), the winter solstice was considered the start of the new year.

In the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220), Dongzhi was an imperial holiday marked by the recess of most official and military services, closure of the borders, and the halt of commerce. For hardworking and tireless people of all classes, it was a rare day of well-deserved rest.

Beginning in the Tang and Song dynasties, Dongzhi became a day of ancestral worship, and the emperor would hold a grand ceremonial ritual to pay his respects to Heaven. The Temple of Heaven in Beijing was constructed some 600 years ago for this function. In the “Qing Jia Lu,” a Qing Dynasty-era document, Dongzhi and the rituals performed on that day were equal to New Year celebrations in importance.

The worship of Heaven is a core tenet of traditional Chinese belief, which emphasizes the importance of following the heavenly way and abiding by natural laws. As the extreme of winter ushered in a new period, it was a time of reflection and pause for the whole empire.

The act of ritual, famously espoused by Confucius, played a central role in the spirit of ancient Chinese leaders and their subjects. Humbling himself and his people before the infinite grace and might of the celestial realm, the ancient monarch gave thanks to Heaven and acknowledged humanity’s place in the natural world.

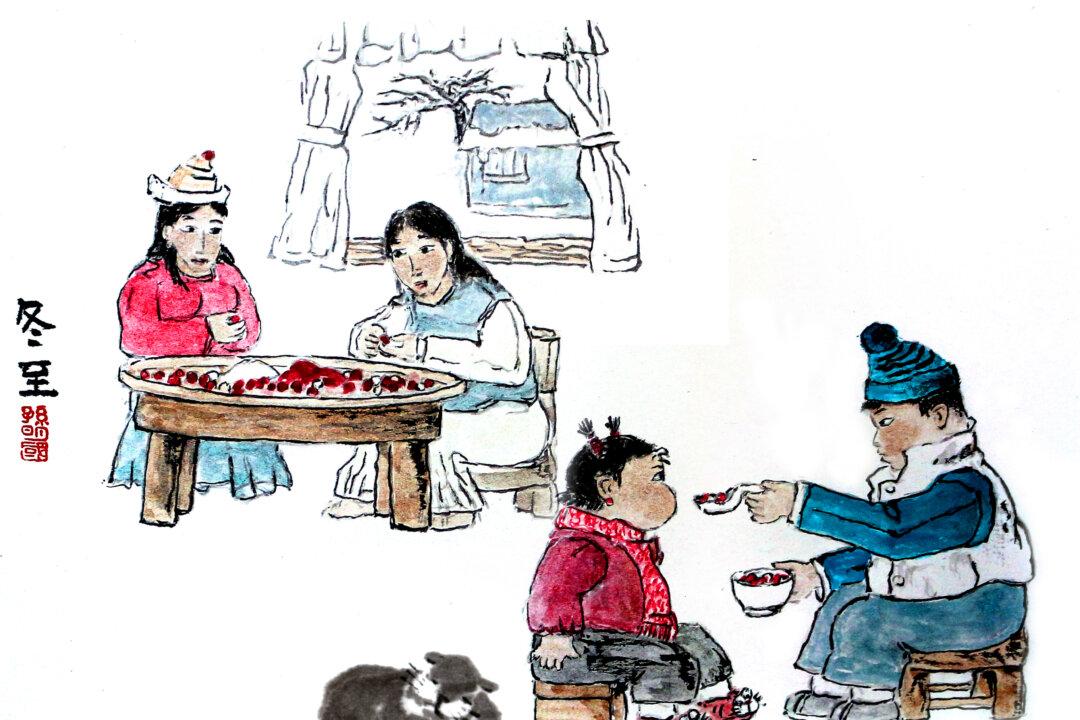

Dongzhi is typically celebrated by eating food such as dumplings and wontons that help the body stay warm. The vastness of China’s geography means that specific traditions vary from region to region—in the chilly north, there is an emphasis on the consumption of meats and drinks considered “hot” in traditional Chinese medicine, while southern habits focus on the tangyuan dumpling, which is a sweet and sticky dish.

The Nines of Winter

Though Dongzhi, being the darkest day of the year, marks the extreme of winter, it is not the coldest. As one folk saying puts it, “There is no real cold until after Dongzhi.” For though the days will become longer, it will still take several weeks for the increased sunshine to be felt across the Northern Hemisphere.

A post-Dongzhi winter of nine times nine or 81 days is accordingly recognized in Chinese folk traditions, whereby each nine-day period represents a different stage of the season.

This 81-day period takes the form of a song, the “Nines of Winter.”

So cold are the first and second Nines

That we do not dare hold out our hands.

During Nines three and four

Water freezes, on ice we go

In the fifth and sixth Nines are to be seen

On the far bank of the river, the willows green

The rivers thaw during the seventh Nine

In the eighth we welcome the wild geese,

Winter sees an end in the last Nine days,

When blossoms and flowers smile in spring.

To mark the passing of the nines, a painting of a plum tree with 81 uncolored blossoms is hung up and every day a new flower is painted red. By the time spring arrives, the painting is complete and fits right in with the real flowers blooming outside.

Another relaxing activity associated with Dongzhi is calligraphy. The learned would compose couplets to illustrate the passing of winter, often using the image of the bent willow, which seems to weep as it weathers the cold in anticipation of spring.