High in a humid tropical forest in the Sierra de Cayey, Puerto Rico, Benjamin Crain and his field assistant were carefully picking their way through the dense growth of moss-clad trees. They were searching for orchids of the genus Lepanthes, diminutive plants that reach no more than two inches in height and are found clinging to the branches of trees.

Pushing past a thick fern leaf, Crain stopped short, overcome by joy. As he broke into dance, his assistant peered curiously at the tiny lentil-shaped fruit dangling from a stem, and resolutely decided Crain was mad. After more than two years studying Lepanthes caritensis, a rare Puerto Rican endemic, Crain had finally found his first specimen bearing fruit.

Orchids, with their tantalizing smells and beautiful variety of flowers have captivated people’s imaginations for centuries. In Victorian England, the obsessive collection of orchids known as “orchidelirium” had wealthy fanatics financing orchid collecting expeditions all over the world. The hunt for rare orchids is not surprising, as orchids are an immensely biodiverse group of plants, containing some 25,000 species, or nearly one in ten of all seed plants. Among the more familiar orchids are Vanilla planifolia, the source of vanilla beans used as a flavoring agent, and Cattleya, a commonly cultivated showy orchid.

Yet this intense relationship between people and orchids now hangs in the balance. In a paper published earlier this year in Diversity and Distributions, Crain and his colleague Raymond Tremblay investigated the link between deforestation and orchid extinctions. They found that deforestation was the most important factor in determining predicted extinction for the next fifty years.

Crain explained, “dozens of species of orchid can live in just a single tree in some cases. Imagine how many there can be in an entire forest.”

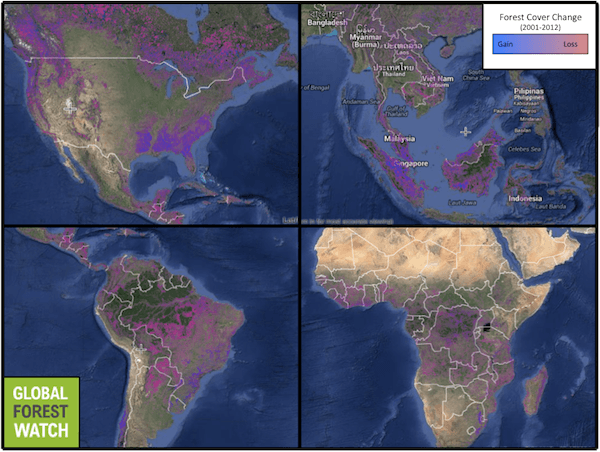

According to the authors, the highest chances of extinction were concentrated in Central America, Haiti and Ecuador. The authors predicted the extinction of 97 Lepanthes species in Ecuador over the next 50 years if deforestation continues at its current rates. Over half a million hectares of forest cover were lost in Ecuador between 2001-2013, while just over 100,000 hectares grew back over the same time, according to the forest monitoring site, Global Forest Watch.

Ecuador is home to the greatest known richness of Lepanthes species in all of Latin America, due to its incredible diversity of geographic and climatic zones. The great variety of niches, areas with distinct environmental and ecological characters, has allowed Lepanthes diversity to flourish. Conserving these varied landscapes is particularly important for maintaining biodiversity, where the number of species in a single hectare can rival that found in entire countries in temperate regions.

Orchids have many unique relationships with other organisms, including specialized interactions with pollinators as well as fungal partnerships that are required for seeds to germinate. In his study, Crain focused on the genus Lepanthes, which alone numbers over 1,200 species. Some of these species can be found only on a single island or isolated mountaintop. Perhaps its most mysterious feature is its most fascinating: Lepanthes do not offer any reward to their pollinators, and only two instances of actual pollination have ever been witnessed. Lepanthes, as well as several other genera of orchids, attract their pollinators through an adaptation known as sexual deception. As Crain explained, “literally, the gnat thinks it is going to get some action, clasps on to the flower, goes to town, and thereby get the pollinia (masses of pollen grains) stuck to its abdomen. When it visits the next flower, the pollinia contact the stigma of that flower, and fertilization takes place.”

For Crain, the fascination with orchids extends beyond academic study. “One of my favorites is Bulbophyllum longissimum- it smells like fresh cotton candy to me and fills the whole room with delight!"

According to Crain, it is what orchids represent, the implausible variety of forms and beauty that arise from evolution, that is truly mesmerizing.

“For all the seemingly crazy things orchids do, when you really look at it, there is always an answer founded in ecology and evolution that helps to explain their seemingly strange behavior.”

Because of their extreme diversity and close-knit connections within their ecosystems, biologists consider orchids to be an excellent indicator of an area’s overall biodiversity.

“Orchids interact with so many other species, they can indicate disturbances to these networks before they may be apparent through other lenses,” Crain said. Being such specialists can make orchids particularly vulnerable to change. “These species are dependent on specific environmental conditions and if these conditions are disrupted, the species can show signs of disturbance rather quickly. This makes them good indicators of larger problems in some instances.”

As indicators, orchids can help us identify key areas for conservation and prioritize land use management. In particular, Crain emphasized that conservation must be thought of as a process, not an event.

“Imagine a Lepanthes on single mountaintop: protecting that forest is critical, but if the area surrounding it is deforested, invasive species might become a problem that needs an on the ground remedy,“ he said. ”Furthermore, as climate shifts, the habitat on that mountaintop might be affected- then you have a whole new set of circumstances to deal with, and so the process continues as new goals are identified. Its a big job, but an exciting one!"

Citations:

- Crain, B. J., & Tremblay, R. L. (2014). Do richness and rarity hotspots really matter for orchid conservation in light of anticipated habitat loss? Diversity and Distributions, 20(6), 652–662.

- Crain, B., & Tremblay, R. (2012). Update on the distribution of Lepanthes caritensis, a rare Puerto Rican endemic orchid. Endangered Species Research, 18(1), 89–94.

- Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “UMD Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland and Google.

This article was originally written and published by Julian Moll-Rocek, a contributing writer for news.mongabay.com. For the original article and more information, please click HERE.