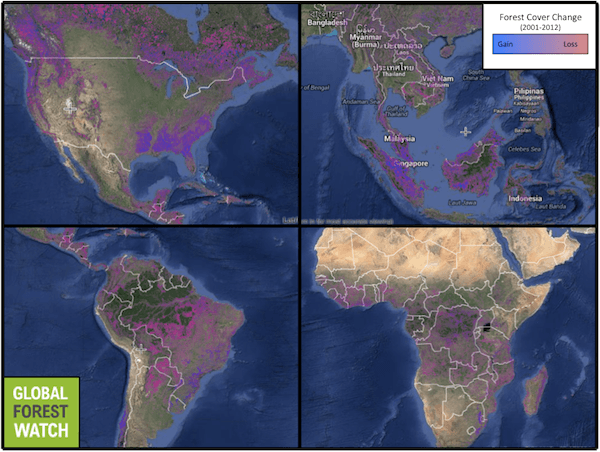

“We live in a world of constant beta,” explains James Anderson, communications officer for the World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Forests program. Nearly every week features are tweaked on the Global Forest Watch (GFW) platform, an innovative mapping system that allows users to track changes in global forest extent, among other features. Constant innovation in technological capability as well as broad social engagement, allowing for more on the ground verification, keep GFW on the cutting edge of forest monitoring.

However, one fundamental thing remains elusive: what exactly is a forest? With forest definitions differing from country to country, and primary forests, secondary forests, and even tree plantations all perceived collectively as “tree cover” by satellite data, how does one accurately keep tabs on land changes?

To confront this issue, GFW has implemented a number of new features in recent months. One of these allows the user to adjust the density of tree cover to suit their own definition of “forest.” Ranging from 10 to 75 percent canopy cover, this reflects the flexible definition put forth by the Kyoto Protocol, which required countries to define a national canopy cover between 10 and 30 percent.

However, the function is not without its caveats; namely, it can only be applied to forest extent and loss, but not to forest gains. As Dr. Fred Stolle, manager of WRI’s Forest Landscape Objective explained, “a signal of a tree falling is very easily recognized, but of course regrowing from a seedling to a bigger seedling to a tree takes a couple years before you see it. How we deal with that, we don’t know yet.” In particular, the difficulty in using remote sensing techniques in classifying the re-growth of forests means serious challenges for monitoring forest restoration goals set by the UN.

One of the group’s biggest priorities is integrating an extensive global land use/land cover map. “Tree cover extent is just tree cover extent,” Stolle said. “It doesn’t say if its primary forest, secondary forest, agroforest or whatever. So that is one of the problems that we have. We would like to get much deeper into distinguishing different forest types.”

Their ongoing work into tree cover differentiation may help resolve the main criticism leveled at GFW and similar remote sensing-based forest-monitoring tools: the lack of distinction between natural forests and plantations. In partnership with Transparent World, a non-profit specialized in remote sensing and mapping projects, WRI is using highly skilled experts to visually distinguish plantations from natural forests in satellite images. The process relies on a set of indirect indicators such as road networks, landscape dynamics and fire frequency to narrow down areas that are then checked by humans.

As Dmitry Aksenov of Transparent World explained, “many countries report plantations as forest to make the picture look nicer internationally. Nowadays it is also a carbon sink issue. Also it may be a way for hiding real deforestation if plantation development is presented as successful reforestation. On the other hand, some tree cover loss detected may not be deforestation but the rotation of plantations after periodic harvest.” To date, the organization has completed the mapping of plantations for Malaysia, Liberia and Colombia, and is hoping to finish a first draft of Brazil, Indonesia, Peru and Cambodia by March 2015. This would represent over 50 percent of existing tropical plantations globally.

Through these new forms of forest data representation, GFW has made policy impacts across the globe. In Central America, a group of countries is cracking down on illegal logging, and will begin using GFW’s forest extent as a baseline for monitoring logging activity, according to Anderson. Pressure is mounting to increase transparency regarding forest data as this becomes the new global standard. Equatorial Guinea, a small African nation that has been notorious for corruption surrounding its lucrative forestry sector recently released its land use information publicly. Improving technologies and information accessibility means corrupt exploitation of natural resources is increasingly difficult to hide.

The continuous evolution of GFW has been more than just technological, according to Anderson. “We started off with a simpler vision, using the best technology available to monitor and map forests,” he said. “But the process itself has been just as eye-opening as the results. We’ve heard a lot more perspectives, and we’ve been able to encourage other people to talk to each other. We are still at the early stages in our global discussion about these things. We are starting to coordinate better, across countries, across organizations, and this is part of that process.”

Citations:

- Hansen, M. C., Potapov, P., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S. A., Tyukavina, A., … Townshend, J. R. G. (2013). High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science, 850(342), 850–853.

- Tropek, R., Sedláček, O., Beck, J., Keil, P., Musilová, Z., Símová, I., & Storch, D. (2014). Comment on “High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change.” Science (New York, N.Y.), 344(6187), 981.

- Hansen, M. (2014). Response to Comment on “High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change.” Science, 981(344).

- Putz, F. E., & Romero, C. (2014). Futures of Tropical Forests (sensu lato). Biotropica, 46(4), 495–505.

- Sasaki, N., & Putz, F. E. (2009). Critical need for new definitions of “forest” and “forest degradation” in global climate change agreements. Conservation Letters, 2(5), 226–232.

This article was written by Julian Moll-Rocek, a correspondent for news.mongabay.com. This article was republished with permission, original here.