Commentary

I’m sure that nearly everyone has heard the term “death by PowerPoint,” and just as many have suffered through those hour-long nightmare briefings where you consider faking going into labor just to get out of the room. And you’re a male. It’s been an ongoing problem in both the military and civilian worlds, almost from the beginning when it was created in 1987 by Robert Gaskins and Dennis Austin. But don’t blame them for all the lost hours of your life—blame the people using it. And blame those above them for enabling the problem to continue.

My question is this. Why are there so many people giving briefings who are absolutely clueless as to how to create and deliver a good one? The military prides itself on clear and concise communications and yet seems unable to apply those rules for briefings. Why is that? Think about this for a moment. List the number of briefings and the number of people-hours consumed in your unit for a calendar year.

Now multiply that by the whole of the Department of Defense (DoD). It becomes very clear that briefings are a major element of military life, so you’d think that there would be training given to officers and non-commissioned officers about how to create and give a good briefing. If there are courses, they are either wrong or they’re not being widely applied afterward.

How do I know that? Because “death by PowerPoint” is still a real deal, and most of you know that what I’m saying is true.

Here are three personal accounts regarding briefings and then I’ll follow up with some helpful hints.

In early 2004, I was TDY (temporary duty) to Edwards Air Force base as a representative of the F-22 systems program office. The program was in a critical phase getting ready to enter initial operating capability (IOC). Every morning there was a briefing to the local colonel about the status of the jets and progress towards IOC. A handful of folks had certain areas of responsibility that they had to brief in the meeting. One of these people was a hapless captain who sat by me and always got shut down by the colonel as soon as he started his slide deck.

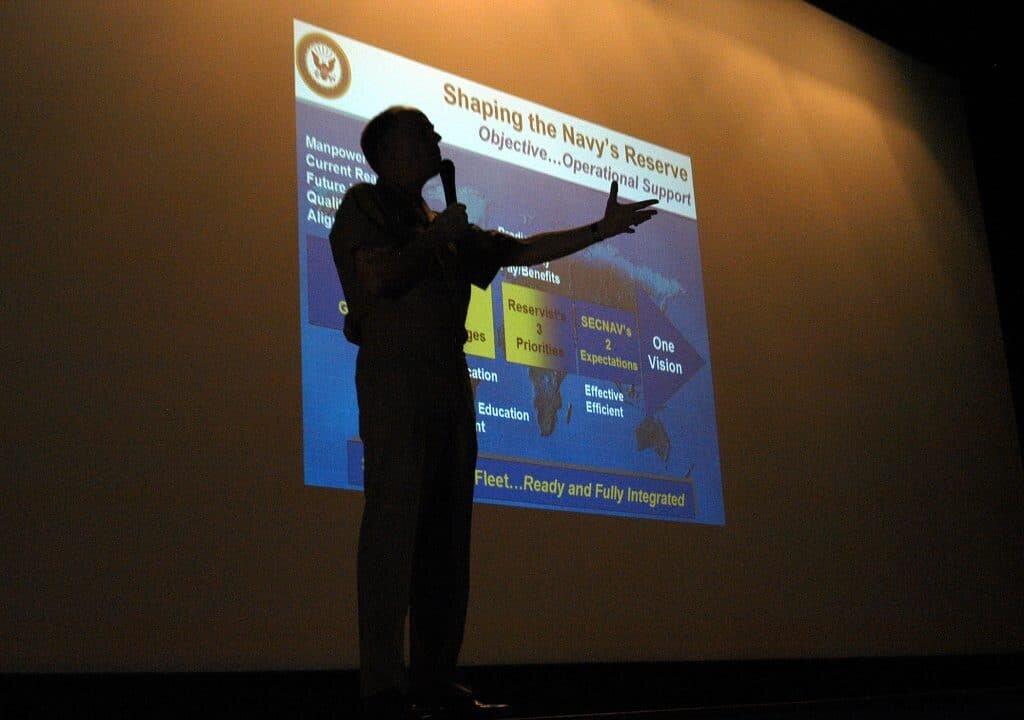

The colonel would get very agitated and cut him off with just a “next briefer!” The captain was visibly crushed and had no clue what he was doing wrong. The essence of the problem was that all his briefing was page after page of huge Excel spreadsheets. You couldn’t even read them on his laptop, let alone on a projected image. And they didn’t say anything useful to most of the people in the room. I pulled the captain aside afterward and offered assistance and told him a little about my background. He agreed and sent me the files and in about an hour created a new briefing for him.

I boiled all those spreadsheets down into six bullet points on two slides. When he looked at it, he freaked out and asked what would happen if the colonel wanted to see the data in the spreadsheets? I told him to have them ready to pull up in a separate file, but I guaranteed that the colonel wouldn’t ask.

He was still balking until I just told him that if the colonel was unhappy with the new format, then I would stand up and take the blame. He reluctantly used the new format the next morning. The colonel perked up and then said, “Finally, you gave me some useful information. Great job, Captain!” Strangely enough, the following day the captain moved to another part of the conference room, wouldn’t make eye contact and avoided me. I guess he couldn’t deal with an old Air National Guard master sergeant crew chief helping him out. Who knows, maybe he is a colonel now. If so, I hope he grew out of his ego.