Three officials with ties to the former leader of the Chinese Communist Party have been punished in the span of five days. For corruption, one was sentenced to jail for 13 years, and another for 16. The third was placed under an internal Party investigation for “severely breaching Party discipline.”

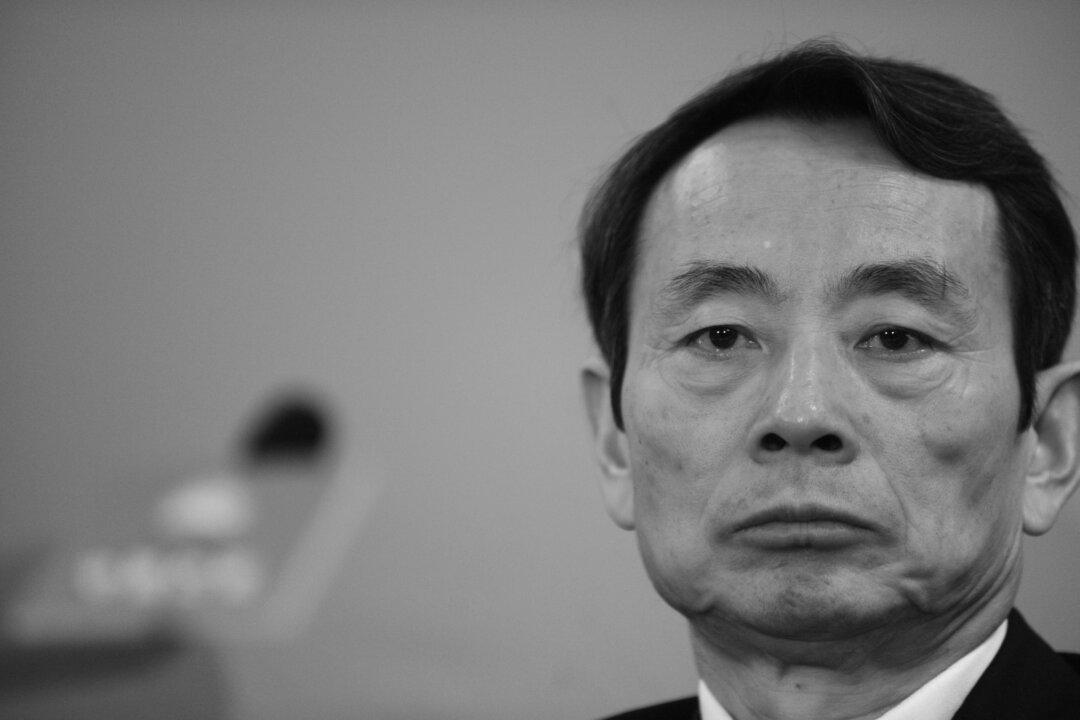

The officials were Li Chuncheng, a former No. 2 of the southwestern Chinese province of Sichuan; Jiang Jiemin, who once headed the agency that oversees state-owned firms, and for many years helmed China National Petroleum Corporation, the country’s largest oil and gas company; and Su Shulin, the former governor of Fujian Province in southern China. Before that, Su was the top leader of oil refining giant China Petroleum & Chemical Corp., better known as Sinopec.

All three are connected to officials closely associated with Jiang Zemin, the Party boss from 1989 to 2002, but who held power behind the scenes for almost the next decade, according to political observers.