The surprising discovery of a fossil fish with a multi-segmented backbone has contradicted long-held beliefs that this type of anatomy was exclusive to land animals.

For decades, scientists have classified fossil animals as being either aquatic or terrestrial based on the number of different segments the vertebrae in their spines can be divided into.

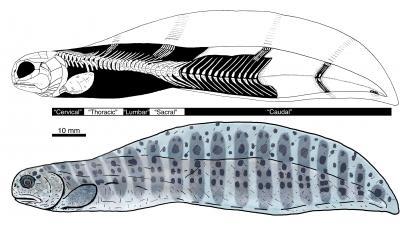

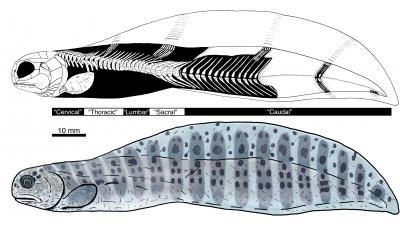

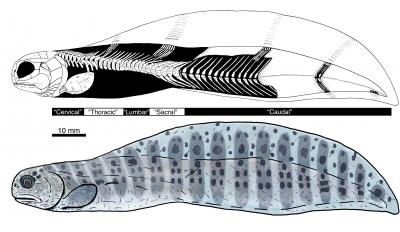

Fish have two segments—body and tail—whereas land animals have five segments—neck (cervical), thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and tail (caudal). The vertebrae in each segment have characteristic features.

Tarrasius problematicus is a 345-million-year-old eel-like fish that inhabited shallow water bodies in what is now Scotland during the Carboniferous period. When it was first discovered, scientists described it as having only two spinal segments like other fish.

Lauren Sallan, a graduate student at the University of Chicago, restudied Tarrasius and discovered it actually had five segments like a land animal.

“The morphology is just completely different in each series of vertebrae,” Sallan said in a press release. “Like a tetrapod, you can tell which segment you’re looking at from the basic morphology.”

She made the unexpected discovery while examining some undescribed fossils at the National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh. Sallan found Tarrasius had heavy vertebral bones clearly separated into five sections, quite unlike other ancient fish species, which had a flexible notochord.

With this new information, Sallan was able to identify the spinal segments in other fossils of Tarrasius, which other paleontologists had not recognized before.

“This was in a different museum from where most of the specimens are, and previous workers had just been looking at the same fossils over and over,” Sallan said. “It’s basically an issue of finding what you expect to be there instead of what’s actually there.”

Tarrasius had no hind fins and a long dorsal fin, so despite having an elaborate spinal column, it was clearly a swimmer and could not walk. The backbone might have helped the fish when it was swimming quickly.

“I think it must help with stiffening the body, because the tail is so flexible,” Sallan said. “If you look at the general shape, it’s more like a tadpole or an early tetrapod, so it might just function to hold the body steady because the tail is flapping.”

Sallan’s discovery means that scientists can no longer presume that fossil animals with a complex vertebral anatomy were walking on land.

“You can’t use this trait to say that something was definitely on land or to identify a tetrapod, which is the way it is used in the field now,” Sallan said.

“It’s the last trait to fall. First, limbs were thought to show that a species was on land and walking, and now the vertebral morphology doesn’t mean that they’re on land either.”

The study was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B on May 23.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.