A recent article about coal miners in China described the story of a 50-year-old man who is dying from black lung disease so that his children can go to college.

Lan Tianzhong, from Sichuan Province, is one of 16 workers at the Taixi Coal Mine in Beijing’s Fangshan District, who were diagnosed with occupational pneumoconiosis, also known as black lung disease, in 2010. The men sued the mine and were each awarded a one-off payment of 80,000 yuan ($12,800) for medical expenses and disability compensation, according to a report by Beijing News on March 20.

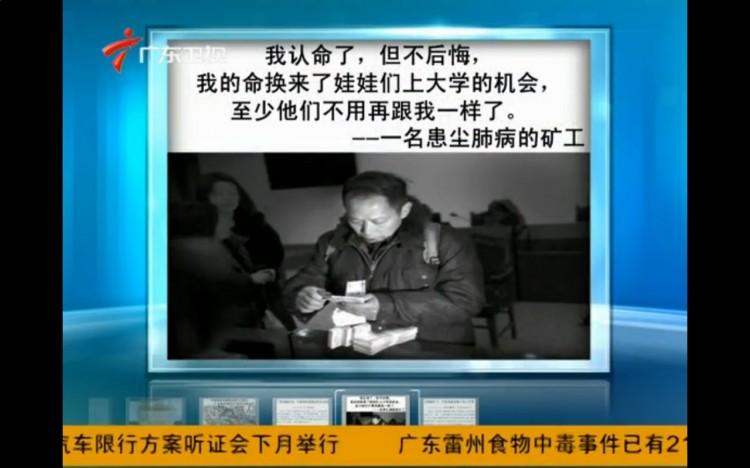

However, the workers only just received their settlements after petitioning the court in December 2011. Lan came to Beijing’s Fangshan Court to collect his payout, and was interviewed by Beijing News.

He described the terrible conditions in the mine, where all the men were constantly covered in coal dust. “After three days we'd start to cough, and even our phlegm would be black,” he said. When Lan began his third year in the mine, he prepared his will before leaving home for work.

The men were working for 2,000 yuan ($322) a month, which was enough to cover their families’ expenses and children’s tuition. “All I want is for my kids to be able to get out of this poor mountainous region,” Lan said, explaining why the villagers stay at the mines. “I’ve accepted my fate, but I don’t regret it. I am exchanging my life for my children to go to college. At least they won’t have to live the way I did.”

State mouthpiece Xinhua reported on March 8 that the number of people with pneumoconiosis has been increasing by tens of thousands each year, though official figures are thought to underestimate the problem.

Since the 1950s there have only been 749,970 documented cases of occupational diseases of which 676,541 were pneumoconiosis, with 22 percent or 149,110 of those people now dead. As of 2010, there were 527,431 pneumoconiosis patients in China, according to the Ministry of Health.

A Jan. 17 report by state-run China News said that only about 10 percent of the pneumoconiosis patients have been formally diagnosed and treated.

Lan Tianzhong’s story triggered heated discussions on the Internet, with some drawing attention to the gaping chasm between rich and poor in China.

A Beijing netizen commented: “The saddest thing is even if the children graduate from college, they might not be able to live a decent life. One can exchange one’s life for college, but he only has one life. What can he exchange for his children’s jobs, houses, and safety…?”

Another said that China’s gross domestic produce is “filled with blood and sweat.”

Li Chunni, who works for a pneumoconiosis charity called “Love for Clean Air,” blogged: “Counting that money is more like counting the days left to live. How much does a life cost?”

One Internet user referred to Party leader Xi Jinping’s recent speech about a “China Dream”: “Forget about this dream and that dream. It’s just one thing: respect for life!”

Translation by Virginia Wu and Sophia Fang. Written in English Cassie Ryan.