In July the Chinese stock market suffered its worst-performing month in nearly six years, as Beijing’s heavy-handed intervention to stem market losses raised more questions than answers for any investor with China exposure.

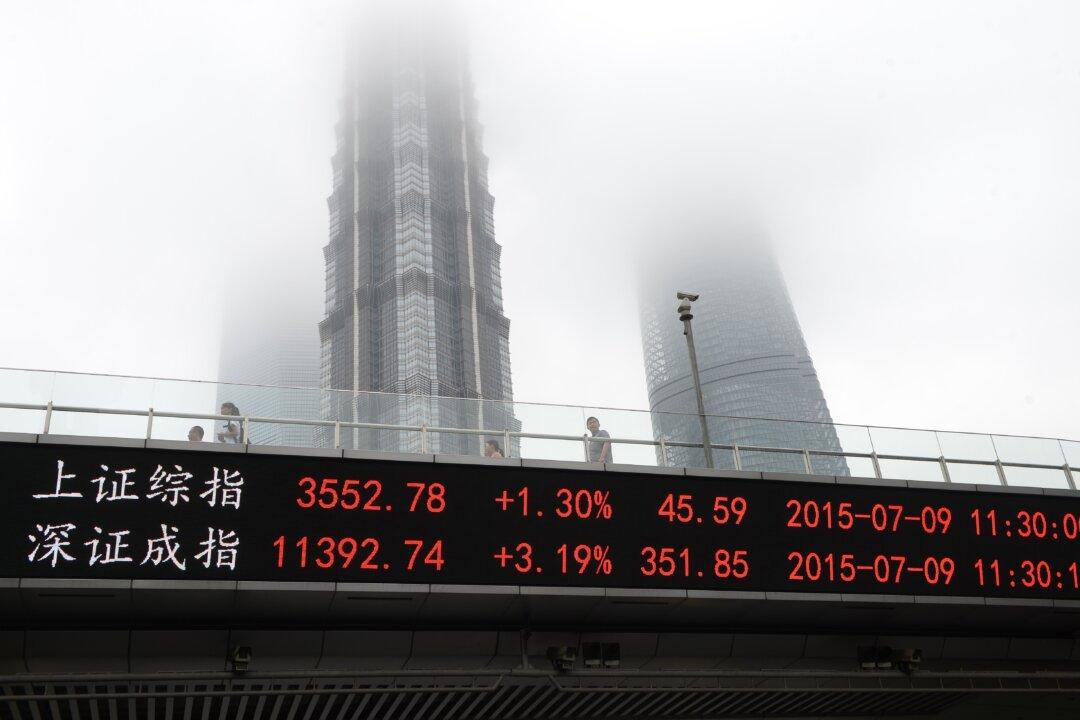

The Shanghai Composite Index fell 10 percent last week and 14 percent for the month of July, the worst one-month loss since August 2009.

But that doesn’t tell the entire story—the market has been beset by massive volatility.

A 32 percent drop between June 12 and July 8 preceded desperate measures from the Chinese Communist Party to stem the losses, including propping up margin finance firms, banning short selling, and instructing state-owned funds to purchase blocks of shares. The Shanghai Composite temporarily rallied 18 percent through July 23, but receding confidence in Beijing’s ability to manage the markets and uncertainty of future policy have resulted in elevated volatility including wild intraday swings.

Despite the selloff, Chinese stocks still look overvalued. The median price-to-earnings ratio of stocks on the Shanghai Composite is around 40, more than double the same ratio for the S&P 500 Index.

Flight from Banks

For investors, there are a few takeaways from the recent Chinese stock market gyrations. The Chinese financial sector must be avoided, especially the large banks. The banking sector faces two massive hurdles—it’s been soaking up the risk to finance the stock market bubble and at the same time being squeezed by a low interest rate environment.

China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) said last week that recent efforts to bolster the stock market was partly to combat “systemic risk” of falling stock prices. But left unsaid in that announcement was its efforts were actually creating gigantic systemic risk in the banking sector.

Reuters reported July 28 that Chinese banks were trying to “get to grips with their financial exposure to the stock market.” That’s a difficult task given the number of loans Chinese banks gave to gray market firms such as smaller commercial banks, asset management companies, consumer finance firms, and trusts.