China’s national college entrance examination, held every June, is the most serious and arduous test that teenagers in China face. Families can sometimes stake everything on the success of one of their children in such exams, which determine which universities the children can go to, and thus to some extent the course of their lives.

For some in China the pressure is simply too much—and in recent months a wave of suicides and attempted suicides have been reported.

“I abandoned my body and my soul, but I’ve always been here, looking at the sky and the earth,” said a note found on the school desk of Xiaofeng [an alias], a senior at the Pingyang High School in Wenzhou City, the capital of China’s prosperous Zhejiang Province.

His body was found in a nearby river, and coded messages he left indicated that it was a suicide. This is despite the fact that Xiaofeng had always been in the top 10 of the class.

A senior at the Tsinghua Experimental School in Shenzhen made an unsuccessful suicide attempt also in May, stabbing herself in the stomach with a fruit knife. The scene was caught on surveillance footage and she was taken to hospital where she remains in critical condition. The school suspects that the psychological pressure of the impending exam became too much.

Other media reports tell of seniors jumping off school buildings, or leaping out of windows. In March, a student jumped out of the fifth-floor window at 7 p.m. at a school in Zhejiang. Chinese children often study late into the evening, given how competitive and demanding the environment is. He died in hospital.

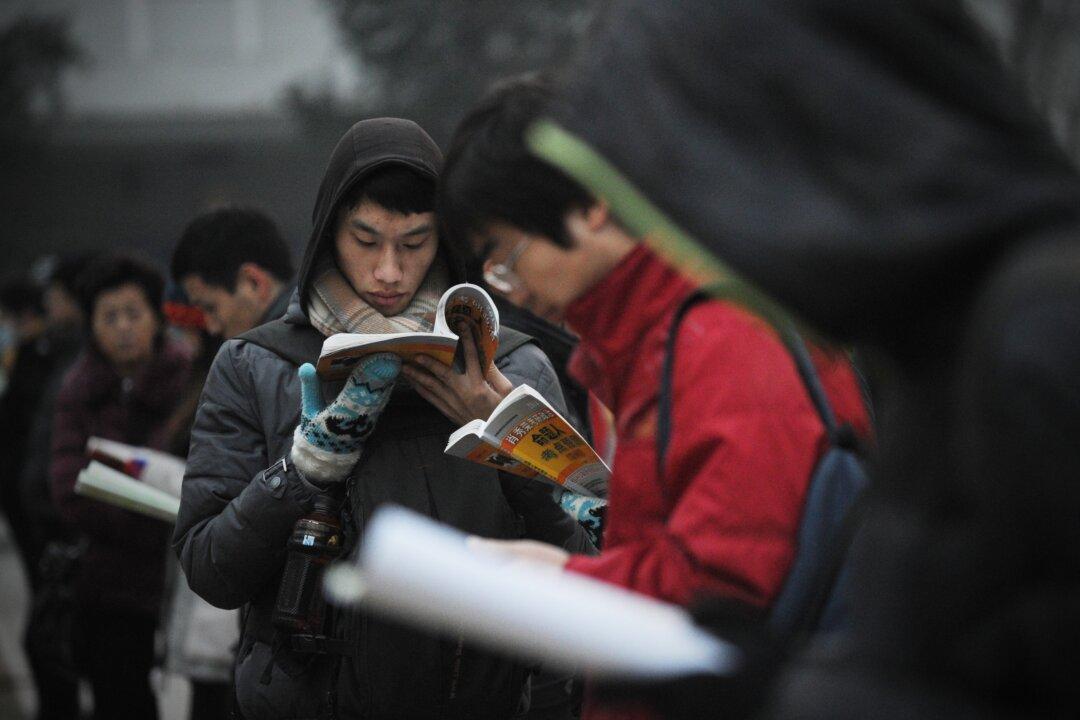

The National College Entrance Examination, called Gaokao in Chinese, effectively decides which university a student can go to. Senior high school students around the country take the exam on June 7 and 8. They are tested on their knowledge in mathematics, English, and either the humanities or the sciences.

High schools are ranked on how well their students perform, so for the kids, pressure to perform comes from both parents and teachers.

June is often called “Black June” because of the nervousness and panic that the test can bring to students, parents, teachers, and schools. Not only is the preparation stressful, but waiting and dealing with the result can also be a cause of anxiety. Many suicides are reported after the results are released, as students fail to achieve the grades expected of them.

Students have been known to protest the long hours of schooling and the heavy homework required to prepare for the tests. A letter published on a government website of Huinong District in Ningxia, southwestern China, complains that students at the No. 21 High School have to stay at school for 11.5 hours a day, and aren’t allowed outside. “We students are so depressed!” the letter says.

Being stuck in school for 10-12 hours a day has become normal in China, though. After that, students then go home often with 2-4 hours of homework to finish. Tutorials occupy the weekends, and little time is left over to socialize, connect with nature, or take up a musical instrument.

Suicide was the top cause of death among Chinese adolescents and young adults in 2013, according to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. In many Western countries unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death for people in that age bracket.

Scholars in China have pointed to the school evaluation system, which relies strictly on standardized tests and scores, as being at the heart of the problem. Cheng Pingyuan, professor of Social Development at Nanjing Capital University, has said in papers that the model needs to be changed fundamentally: to a more personalized and diverse style of testing that allows individual abilities to be put into play and measured. A humanistic education and inculcation of values, rather than narrow memorization or technical tasks should also be part of education, he argues.

The score-centered basis of the system also leads to conflicts between teachers and students, Cheng’s research shows. Teachers scold the students in their charge, and are generally unsympathetic to the enormous strains they’re under.

Chinese media reports say that at least 14 students killed themselves last year after being criticized or verbally abused by their teachers.

This happens because failure to achieve a high score can reflect badly on the teacher or the school. Those who don’t get good grades on major subjects are therefore considered “bad students” by the teachers, who disregard talents in other areas, and are not encouraged to consider the students’ overall personal development. Professor Cheng says that the environment of intense study, competition, and strict grading, ends up undermining actual learning, creativity, and independent thinking.