China’s first overseas military base—located at a critical chokepoint for global trade looking to navigate the Suez Canal—could be a geopolitical game changer, but it has less impact in military terms.

Establishing the Djibouti base at the Horn of Africa signals the Chinese regime’s long-term strategic intentions, say experts. A Chinese Communist Party that once pledged to stay out of the affairs of other countries is now building military capacity far beyond its immediate border.

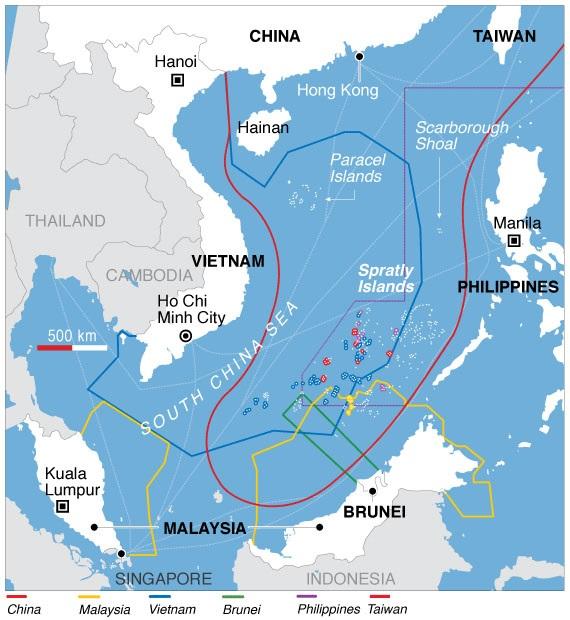

But the change is less important to China’s military capability than to its ability to directly intervene in global shipping. Earlier this year, the regime convinced Panama—home to the world’s other great shipping pass—to cut ties with Taiwan and fully back China’s claim on the island nation, which the regime describes as a breakaway province.

These moves follow a series of port deals that have given the regime the ability to ensure its critical shipping lanes.

Until now, however, none of those facilities have been for direct military use.

Establishing the Djibouti base reverses a long-standing military policy, said Gabe Collins, a researcher and co-founder of the analysis website China Signpost.

“If you look at basic foreign policymaking throughout the vast majority of the PRC’s history, overseas bases are major red lines they weren’t willing to cross, and they pretty clearly crossed that now,” he said. Collins co-authored a report on the base and its implications two years ago.