Weeks before an important political conclave in Beijing, rights activists and lawyers around China are urging the authorities to ratify the basic document enshrining human rights: the United Nation’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The ICCPR, as it is called in the rights community, is a foundational document setting out the basic rights that are mostly taken for granted in modern democratic societies. Chinese activists would like to see some of those same freedoms in China.

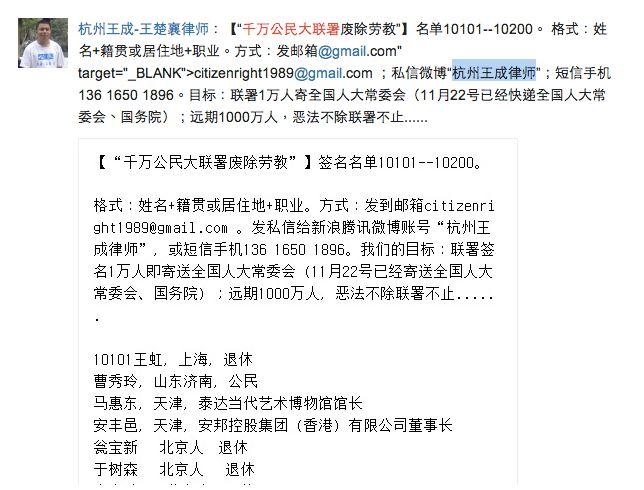

Prominent lawyers Wang Cheng and Tang Jingling are the founders of the Citizens’ Rights Statement, in China. They aim to gather 1 million signatures on their online petition prior to the “two meetings” in China’s capital on March 3. At that time the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference will meet. The first is a rubber-stamp legislature, while the second is a Party-controlled advisory body.

“The current problems in society are very serious,” Wang told the Epoch Times in an interview. He pointed to official corruption, growing antagonism between the public and the regime, the widening wealth gap between people with ties to the Party and those without ties, degradation of the environment, and the decline in general morality in society. Chinese officials have not addressed these issues, he said.

Implementing the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, however, would mean instituting democracy and ensuring that the country operates within a constitutional framework, Wang said.

China signed the Covenant 16 years ago, but it is one of only seven signatories who have not yet ratified it. While 167 countries have completed the process, China has no reason to refuse, Wang said.

The Communist Party, however, has jailed many rights activists who seek the same concessions as Wang and his colleagues. Party leaders see calls for civil rights as an attempt to sabotage their political regime.

Wang has been collecting signatures through his account on Sina Weibo, a Twitter-like microblogging platform in China. Intellectuals, lawyers, farmers, workers, and others have signed up, he said. Though he has lost three Weibo accounts since he began the campaign, he simply opens new ones, he said.

Guangzhou-based rights lawyer Tang Jingling told Sound of Hope radio that their short-term target is 1 million signatures, and their long-term target is tens of millions, until the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) ratifies the convention.

Echoing Wang’s concerns, he said that China’s human rights issues must be resolved as soon as possible.

“The core of the covenant is the right to life, freedom from torture, and the right to a fair trial, the right to liberty and security, freedom of movement, the right to freedom of thought, freedom of conscience, freedom of expression, freedom of religion, the right to freedom of assembly, of procession and liberty, freedom of association and the right to stand for election, including the right to vote,” he said.

Many activists and dissidents in China have been jailed or put under house arrest for calling on the Chinese Communist Party to grant those rights.

“This is not the first time that people have asked the authorities to approve and implement the convention,” Tang Jingling said.

“Early in 2008, prior to the Olympic Games, as many as 10,000 people put their signatures on a petition, but the authorities didn’t respond. More than 100 citizens asked the NPC to approve the convention in March 2013 during the congress, but it ended up with the organizer and activists arrested,” he continued.

Sophie Richardson, China director of Human Rights Watch, pointed out the contradictory situation that the Chinese authorities have put themselves in, in a statement last October: “China wants to join the U.N.’s top human rights body, but it won’t submit itself to the standards that body is sworn to apply.”