“Chunwan,” the New Year Gala broadcast by China Central Television (CCTV) every Chinese New Year’s eve, has a yearly viewership of hundreds of millions. In the 1980s and 1990s, it used to be the only new year’s eve show on television, humming away as the family rolled dumplings. The show is still a major event in China today, given that flagship channels on provincial television networks are mandated to broadcast the Gala rather than their own programming.

Chunwan is usually over 4 hours long—so imagine a Super Bowl halftime show that is a little longer than the game itself. A key difference is that Chunwan has an audience several times greater than the Super Bowl’s, thanks to China’s population. This makes it probably the most watched annual television event in the world.

But in China, no state-run, premier television event can confine itself to mere entertainment. As one Internet user remarked recently about the forced confession of the Taiwanese singer Chou Tzu-yu: “China’s politics looks pretty entertaining, and the entertainment industry looks pretty political.”

Chunwan has a long history of serving the Party’s propaganda needs: there are red songs with titles like: “Without the Communist Party there would be no new China,” dances showing the “happiness” of life under the leadership of the Party, and celebrations of the “national achievements” of the year past.

Even CCTV openly proclaims: “Chunwan is a premier political task assigned to CCTV by the Party and our nation.”

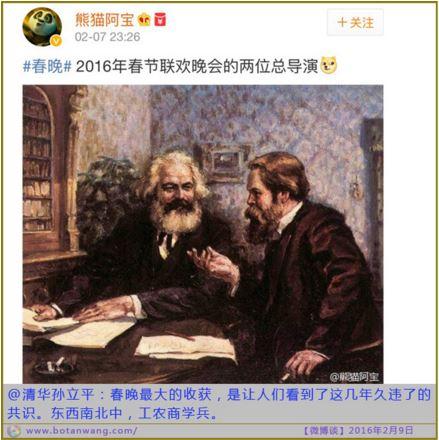

However, Chunwan in 2016, the Year of Monkey, seemed to go too far in executing its political function. There is a rare consensus among Chinese netizens that this year’s Chunwan is the worst in decades. “It’s not even close. I apologize to all previous Chunwan that I labeled as ’the worst,'” one viewer wrote.

A large number of comments on Sina Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, discuss how over-the-top the political content felt this year. A widely forwarded post said: “In previous years, we saw entertainment shows mixed with some political elements; this year, we saw a political show mixed with some entertaining elements.”

Another top-rated remark said: “I feel like I just watched a 4.5-hour long Xinwen Lianbo,” CCTV’s flagship mouthpiece news program.