When Hong Kong economics professor Larry Lang Hsien Ping gave a closed-door speech in Shenyang, China, first reported by The Epoch Times, he predicted that China would soon experience an “economic tsunami” in large part due to burgeoning local government debt. The performance of bonds recently issued by China’s local governments helps illustrate Lang’s thesis that “every province of China is Greece”—bankrupt with no easy way back to solvency.

The size of the debt accrued by China’s local governments cannot be accurately estimated from China’s official figures, which are notoriously unreliable. According to data published by China’s National Audit Office in late June, the country’s local government debt had reached 10.7 trillion yuan (US$1.68 trillion) by the end of 2010.

Lang claims that the actual debt is about 36 trillion yuan (US$5.66 trillion). His figure includes 19.5 trillion yuan from Moody’s July estimate plus 16 trillion yuan borrowed from state-owned enterprises. China’s total gross domestic product is 40 trillion yuan (US$6.2 trillion).

Local Government Bonds

In an effort to resolve the local governments’ debt crisis, China’s State Council in late October, for the first time in 17 years, approved a pilot program to allow four local governments to sell bonds directly. Shanghai was the first to issue 7.1 billion yuan (US$1.12 billion) in bonds on Nov. 15, followed by Guangdong Province, Zhejiang Province, and Shenzhen City. However, the yields of all four new government bonds were exceptionally low, even below the current rate of central government bonds.

On the surface, the sale of the new bonds was met with strong demand. However, some analysts commented that behind the “distorted” bond yield rates is an “abnormal” relationship between power and market, which goes against the market-driven mechanism.

Chinese economist Dr. Ma Hongman said in an article published on Yangcheng Evening News that the lower bond yields are due to the central government’s direct credit endorsement of the bonds.

“Banks who underwrote the bonds would rather lose a little to help local governments reduce their borrowing cost now in the hope of attracting large deposits from them in the future, which translates into good overall profits,” reported Hong Kong’s Economic Journal, as quoted by Voice of America.

“This kind of administrative measure might help push the sale of the bonds at the beginning, but in the long run it won’t resolve local governments’ debt crisis,” noted Beijing-based Caijing Magazine.

Next... Breach of Contract

Breach of Contract

Prior to the pilot project, China’s local governments raised funds for infrastructure construction mostly by selling urban construction investment bonds.

In his four-hour Shenyang speech on Oct. 22, Lang said that based on investigation by his research team, local governments had sold 483 urban construction investment bonds, of which 33 percent had negative cash flows.

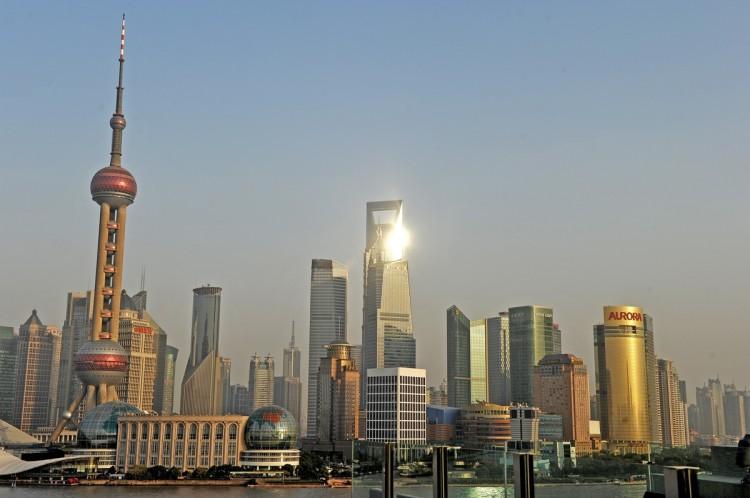

Lang took one of the “good” districts in Shanghai as an example. Minghang District had a debt ratio of 46 percent and a debt of 15 billion yuan (US$2.36 billion), with one billion yuan (US$157 million) in annual interest payments. The debt ratio of another district, Hongkou, stood at 190 percent, with a negative cash flow of 200 percent.

Hongqiao District, an upscale business district in Shanghai and one of the largest hubs in the world, breached the contract in June on a 20-billion yuan (US$3.24 billion) loan it had borrowed from a state-owned enterprise.

In fact, all levels of government in Shanghai have gone bankrupt, Lang said.

The Party secretary of a district government in Zhengzhou City in Henan Province is Lang’s former student. According to Lang, he said that he cannot afford to pay his staff salaries at the end of the year but can do nothing about it, except continue to lie to people and wait to be transferred to a new post next year.

Trading Halted

The debt crisis started on April 26, when Yunnan Province became the first province to breach a contract on an urban construction bond, followed by the provinces of Sichuan, Guangdong, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and others. Consequently, trading of urban construction investment bonds has halted almost completely in China since July 8, Lang said.

Because the debt obligation is unclear, the new local government bonds will likely take the same course.

Liu Ligang, head of Greater China Economics at ANZ (Australia and New Zealand) Banking Group, noted in an article in the Chinese edition of Financial Times that the new leader of a local government is often reluctant to resolve debts left by his predecessors but tends to raise funds to do “big” projects, thereby incurring more debts.

Unless there is proper financial regulation to control excess spending, local governments are still likely to go bankrupt due to mounting debts, Liu said.

Zhou Yixing, a columnist on cnhubei.com, a Web portal of Hubei Daily News, wrote that if the same debt-incurring pattern continues, selling local government bonds is just “borrowing new debt to pay off the old” and might even introduce bigger debts.

Lang said it has become impossible to resolve the Chinese regime’s local government debts and “allowing local governments to sell bonds directly is like drinking poison to quench thirst.”