Yukui Liu is a doctor of Chinese medicine now living in the United States. The story that follows is his personal experience, that of his mother and father, and of Chinese communism, from the Cultural Revolution to today. The account was prepared and edited as an exclusive memoir to be published in The Epoch Times. The names have been changed to protect family members still in China.

I grew up in communist China during the Great Cultural Revolution. Life for Chinese people was bitter when the state-initiated “class struggle” swept through our country like a wildfire of violence, lasting ten long years. Although the central figure of this story is my father, the things perpetrated upon him affected our entire family. For me, the eldest son, the suffering and stress is still ever-present in my mind—as intended by this regime that uses extreme brutality to make examples of people in order to spread fear and subjugate the masses.

When I was six years old, in 1963, during a period called “Socialist Education Movement” just prior to the Cultural Revolution, our family was banished to a small village in northeastern China because my father had received a few years of Japanese education during World War II. The area we were sent to was poor and undeveloped, without transportation or electricity, and there were no jobs. My father was a university professor and suddenly had to become a farmer to support the family—my parents, grandmother, younger sister and myself. Since my father had never farmed before, we could not grow enough food on the countryside paddies, and we suffered much hunger during those years. My parents had no income, so my mom raised a few chickens to sell eggs so she could buy paper and pencils for me to go to school.

It was an unusually cold winter in the year of 1968, when I was 11 years old. It continued snowing every day, covering the village. We never saw the sun or the moon all winter, while enduring freezing cold days and nights of up to -30 degrees Celsius (-22 degrees Fahrenheit). I was attending the village elementary school. One day, an event at school caused an unforgettable blow to my soul. As usual, I walked the two miles of snow-covered mountain road to school. But when I walked into my classroom, there was nobody there—no teacher, no students. Instead, the walls were covered with posters filled with Chinese brush characters in black ink. As a fourth grader I could already read all the Chinese characters, and I was startled by the content of those posters. They were all attacking my father, saying things like: “Overthrow counterrevolutionary Liu Shibao!”

Scared and confused I walked around the campus and saw more of these posters everywhere, all over the school. I realized that many village people, including some students, had posted these.

This was in the third year of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a political movement launched by the Chinese communist party (CCP) in May 1966, to control and purge the educated elite, including teachers and scientists, through terror and persecution. This cruel and destructive movement in total lasted for 10 years and spread all over the country.

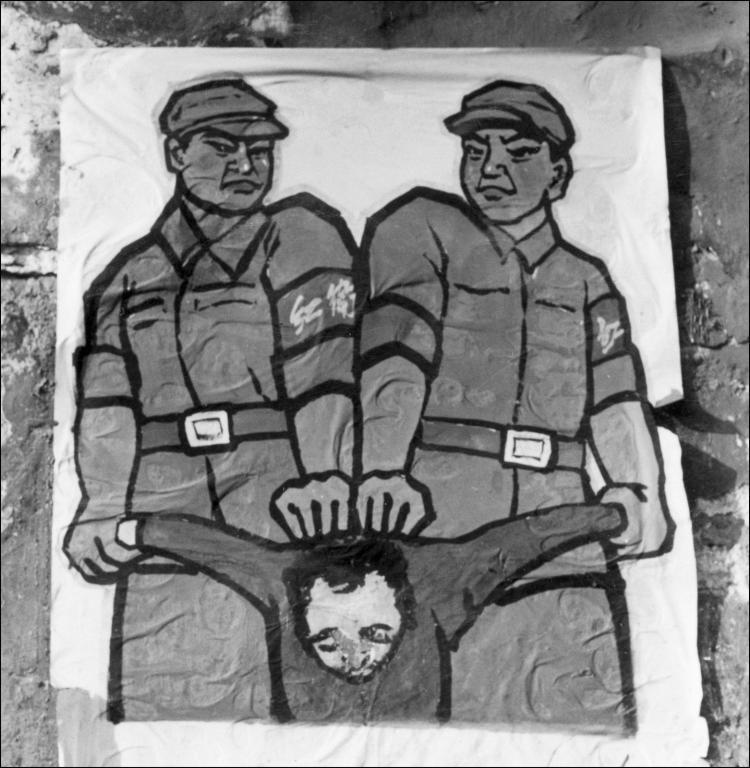

From that day on, my father was ordered to attend nightly public criticism meetings, also called “struggle sessions” (Pi Dou Da Hui or Pi Pan Da Hui in Chinese). Several hundred villagers were also ordered by authorities to attend and to “struggle” with the “struggle target” or “class enemy” by verbally, and sometime physically, abusing him or her.

My father was labeled a “history counterrevolutionary” and was required to have that title pinned to his clothes on a card at all times, in public and at home. The criticizing meetings were organized by a Cultural Revolution Leading Committee, a special governing agency of the Communist Party. During the meetings my father had to kneel for over three hours while people berated him loudly and violently. People shouted over and over: “Beat down Liu Shibao! Beat down Liu Shibao!” Some people made up false stories about my father, making people hate him. Some people became very riled-up and out of control that they would spit at him and beat him.

With this kind of abuse being repeated over and over, night after night, my father was eventually nearing breakdown. He became sick and exhausted, always dizzy, with headaches, nausea, and sometime he nearly passed out. His emotions went between anger, fear, hate, hopeless, helplessness, and depression.

We were very scared and worried for my father. My grandmother was crying all the time. My mom and I were afraid that he might die. Every night before the struggle sessions started, my mom and I hid outside the meeting place. With temperatures at -22 degrees Fahrenheit, we were shaking from the cold, and our feet were painful and numb. Even so, we still kept staying there to listen to the meeting, and maybe help my father, should his situation become dire. My mom’s plan was that if my father became too weak, we would go into the meeting room and kneel down in front of the village people, begging them to stop.

“If they still have a little bit of human heart left, they may stop, and we may be able to save your father’s life,” mom said.

The struggle session sometimes went on until midnight. After it was finally over, we helped my already exhausted father to walk back home. On the way home, we passed a well—the only well from which the village people got their water. My mom always worried if my dad walked home by himself, he might commit suicide by jumping into the well. This was another reason why my mom and I waited outside the meeting place during those freezing cold nights to take my father back home.

Such dark days and nights continued. Each struggle session produced more fake stories about my father, so people’s hatred against him became ever more extreme. Those fake accusations were made up under pressure from the leaders of Cultural Revolution Leading Committee, the Communist Party members. Without providing any factual evidence, these fabricated reports were used to slander and destroy “the enemy.” They were loudly read in front of the people and then posted on walls at school and all public places throughout the village, for everyone to see.

The frenzied and irrational mob-like environment of these class struggle meetings created such hateful energy that it even pushed people into a killing mood. Many innocent teachers, professors, engineers, scientists, and religious leaders were thus beaten to death. My father was facing this situation too. Our whole family was in fear that any day my father would be beaten to death.

One night, after the struggle session had finished at about 1 am and all lights in the village were out, with everything dark and quiet, we had a visitor come to our home. Our family had just fallen into light sleep, when my mom heard a man’s voice outside our house, saying over and over: “Brother, open the door! Brother, open the door!”

My mom ignored the voice as she thought it was an illusion in her head because she worried about my father too much. Then I too woke up, but I was scared and kept quiet. However, the man’s voice kept pleading, “Brother, open the door!”

We finally realized that it was my uncle, my paternal aunt’s husband, who was outside our home in this dark, cold night. He said he had something important to tell us.

My uncle was one of the members of the Cultural Revolution Leading Committee in our village, and a Communist Party member, and he was a major participant in the criticizing meetings against my father. His wife, my father’s younger sister, was very worried about this, but neither she nor my uncle could have any contact with us because anyone who has close relationships with an “enemy” of the Cultural Revolution would also be in trouble. So in public, my uncle had to actively participate in all the activities of the struggle sessions against my father, but when he came home, he would suffer from guilt, especially when he saw his wife silently crying. Sometime my aunt would ask him if there wasn’t any way that he could help, but his answer was always, “There is nothing I can do, I am upset about it too.”

My uncle, and countless millions of Chinese people, were trapped like this. The class-struggle was devised by the communist regime to force people into doing the regime’s dirty work for them. Many people were thus drawn into committing crimes against others against their own conscience, simply out of fear. The regime’s plan was to replace people’s conscience with the “party spirit.” Party spirit is about putting the regime’s survival first, and treating one’s “enemies” without mercy or humanity even though they may be one’s own family members or best friends.

My uncle finally could not endure and be silent anymore because the criticizing meeting was supposed to be upgraded to another level—physically torturing my father. My uncle told us that there had been a meeting about it within the leadership on that day, and afterwards they started to prepare many torture instruments such as bricks, wire, metal whips and sticks. It was decided that in next criticizing meeting, they would force my father to kneel down on the bricks, and they planned to bundle together several bricks and hang them on my father’s neck. Then they would have people use the metal whips and sticks to beat him.

They decided that if my father would still not admit to being a Japanese spy, they would beat him to death. My uncle has been a close friend of my father’s before the Cultural Revolution. He knew that my father would not admit to something that is untrue. He also knew that this would be the last struggle session, and that my father would be killed if they did as planned.

The conflict in my uncle’s mind became intense. If he kept silent, my father would be killed, and if he tried to stop those people, he would then be in the same situation as my father. If he warned my father about it, it would be considered that he had divulged secrets to the enemy, and he would become a counterrevolutionary himself and receive the same or worse torture.

After painful mental struggle, my uncle decided to secretly come to our house and persuade my father to flee. My uncle had thus walked through the very heavy snow in the dark of night. He had to be very careful and quiet not to make any dogs bark. If anyone saw him going to our house, he would have been arrested right away.

We all sat on the floor in the dark room, listening to my uncle talk to my parents in a hushed voice: “Brother and sister, please take my words very seriously. They have already prepared everything to torture brother at tomorrow’s struggle session. The only way to save yourself is to escape before daybreak, otherwise they will kill you. I finally decided to come tell you under risk of my own life. Now there are only a few hours left, so please hurry up and get ready to escape somewhere far away!”

After this, my uncle left quietly, and we hastily moved into action. My mom used the only two pounds of bread flour we had for the entire year to bake a few Chinese pancakes for my father to take along. I sat on the floor, helping my mom by keeping the wooden fire going.

We got my father ready to leave in about 30 minutes. All our family members, including my little sister and my grandmother, were crying as we said goodbye and watched my father gradually vanish into the darkness of the blizzardy night.

With just a few pancakes and 50 yuan my uncle had given him, my father left home in that cold winter night of 1968 to escape being beaten to death at the struggle session set up for the following evening.

End of part I of II of Yukui Liu’s account. Part II will appear shortly, and be linked to this article.

I grew up in communist China during the Great Cultural Revolution. Life for Chinese people was bitter when the state-initiated “class struggle” swept through our country like a wildfire of violence, lasting ten long years. Although the central figure of this story is my father, the things perpetrated upon him affected our entire family. For me, the eldest son, the suffering and stress is still ever-present in my mind—as intended by this regime that uses extreme brutality to make examples of people in order to spread fear and subjugate the masses.

When I was six years old, in 1963, during a period called “Socialist Education Movement” just prior to the Cultural Revolution, our family was banished to a small village in northeastern China because my father had received a few years of Japanese education during World War II. The area we were sent to was poor and undeveloped, without transportation or electricity, and there were no jobs. My father was a university professor and suddenly had to become a farmer to support the family—my parents, grandmother, younger sister and myself. Since my father had never farmed before, we could not grow enough food on the countryside paddies, and we suffered much hunger during those years. My parents had no income, so my mom raised a few chickens to sell eggs so she could buy paper and pencils for me to go to school.

It was an unusually cold winter in the year of 1968, when I was 11 years old. It continued snowing every day, covering the village. We never saw the sun or the moon all winter, while enduring freezing cold days and nights of up to -30 degrees Celsius (-22 degrees Fahrenheit). I was attending the village elementary school. One day, an event at school caused an unforgettable blow to my soul. As usual, I walked the two miles of snow-covered mountain road to school. But when I walked into my classroom, there was nobody there—no teacher, no students. Instead, the walls were covered with posters filled with Chinese brush characters in black ink. As a fourth grader I could already read all the Chinese characters, and I was startled by the content of those posters. They were all attacking my father, saying things like: “Overthrow counterrevolutionary Liu Shibao!”

Scared and confused I walked around the campus and saw more of these posters everywhere, all over the school. I realized that many village people, including some students, had posted these.

This was in the third year of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a political movement launched by the Chinese communist party (CCP) in May 1966, to control and purge the educated elite, including teachers and scientists, through terror and persecution. This cruel and destructive movement in total lasted for 10 years and spread all over the country.

From that day on, my father was ordered to attend nightly public criticism meetings, also called “struggle sessions” (Pi Dou Da Hui or Pi Pan Da Hui in Chinese). Several hundred villagers were also ordered by authorities to attend and to “struggle” with the “struggle target” or “class enemy” by verbally, and sometime physically, abusing him or her.

My father was labeled a “history counterrevolutionary” and was required to have that title pinned to his clothes on a card at all times, in public and at home. The criticizing meetings were organized by a Cultural Revolution Leading Committee, a special governing agency of the Communist Party. During the meetings my father had to kneel for over three hours while people berated him loudly and violently. People shouted over and over: “Beat down Liu Shibao! Beat down Liu Shibao!” Some people made up false stories about my father, making people hate him. Some people became very riled-up and out of control that they would spit at him and beat him.

With this kind of abuse being repeated over and over, night after night, my father was eventually nearing breakdown. He became sick and exhausted, always dizzy, with headaches, nausea, and sometime he nearly passed out. His emotions went between anger, fear, hate, hopeless, helplessness, and depression.

We were very scared and worried for my father. My grandmother was crying all the time. My mom and I were afraid that he might die. Every night before the struggle sessions started, my mom and I hid outside the meeting place. With temperatures at -22 degrees Fahrenheit, we were shaking from the cold, and our feet were painful and numb. Even so, we still kept staying there to listen to the meeting, and maybe help my father, should his situation become dire. My mom’s plan was that if my father became too weak, we would go into the meeting room and kneel down in front of the village people, begging them to stop.

“If they still have a little bit of human heart left, they may stop, and we may be able to save your father’s life,” mom said.

The struggle session sometimes went on until midnight. After it was finally over, we helped my already exhausted father to walk back home. On the way home, we passed a well—the only well from which the village people got their water. My mom always worried if my dad walked home by himself, he might commit suicide by jumping into the well. This was another reason why my mom and I waited outside the meeting place during those freezing cold nights to take my father back home.

Such dark days and nights continued. Each struggle session produced more fake stories about my father, so people’s hatred against him became ever more extreme. Those fake accusations were made up under pressure from the leaders of Cultural Revolution Leading Committee, the Communist Party members. Without providing any factual evidence, these fabricated reports were used to slander and destroy “the enemy.” They were loudly read in front of the people and then posted on walls at school and all public places throughout the village, for everyone to see.

The frenzied and irrational mob-like environment of these class struggle meetings created such hateful energy that it even pushed people into a killing mood. Many innocent teachers, professors, engineers, scientists, and religious leaders were thus beaten to death. My father was facing this situation too. Our whole family was in fear that any day my father would be beaten to death.

One night, after the struggle session had finished at about 1 am and all lights in the village were out, with everything dark and quiet, we had a visitor come to our home. Our family had just fallen into light sleep, when my mom heard a man’s voice outside our house, saying over and over: “Brother, open the door! Brother, open the door!”

My mom ignored the voice as she thought it was an illusion in her head because she worried about my father too much. Then I too woke up, but I was scared and kept quiet. However, the man’s voice kept pleading, “Brother, open the door!”

We finally realized that it was my uncle, my paternal aunt’s husband, who was outside our home in this dark, cold night. He said he had something important to tell us.

My uncle was one of the members of the Cultural Revolution Leading Committee in our village, and a Communist Party member, and he was a major participant in the criticizing meetings against my father. His wife, my father’s younger sister, was very worried about this, but neither she nor my uncle could have any contact with us because anyone who has close relationships with an “enemy” of the Cultural Revolution would also be in trouble. So in public, my uncle had to actively participate in all the activities of the struggle sessions against my father, but when he came home, he would suffer from guilt, especially when he saw his wife silently crying. Sometime my aunt would ask him if there wasn’t any way that he could help, but his answer was always, “There is nothing I can do, I am upset about it too.”

My uncle, and countless millions of Chinese people, were trapped like this. The class-struggle was devised by the communist regime to force people into doing the regime’s dirty work for them. Many people were thus drawn into committing crimes against others against their own conscience, simply out of fear. The regime’s plan was to replace people’s conscience with the “party spirit.” Party spirit is about putting the regime’s survival first, and treating one’s “enemies” without mercy or humanity even though they may be one’s own family members or best friends.

My uncle finally could not endure and be silent anymore because the criticizing meeting was supposed to be upgraded to another level—physically torturing my father. My uncle told us that there had been a meeting about it within the leadership on that day, and afterwards they started to prepare many torture instruments such as bricks, wire, metal whips and sticks. It was decided that in next criticizing meeting, they would force my father to kneel down on the bricks, and they planned to bundle together several bricks and hang them on my father’s neck. Then they would have people use the metal whips and sticks to beat him.

They decided that if my father would still not admit to being a Japanese spy, they would beat him to death. My uncle has been a close friend of my father’s before the Cultural Revolution. He knew that my father would not admit to something that is untrue. He also knew that this would be the last struggle session, and that my father would be killed if they did as planned.

The conflict in my uncle’s mind became intense. If he kept silent, my father would be killed, and if he tried to stop those people, he would then be in the same situation as my father. If he warned my father about it, it would be considered that he had divulged secrets to the enemy, and he would become a counterrevolutionary himself and receive the same or worse torture.

After painful mental struggle, my uncle decided to secretly come to our house and persuade my father to flee. My uncle had thus walked through the very heavy snow in the dark of night. He had to be very careful and quiet not to make any dogs bark. If anyone saw him going to our house, he would have been arrested right away.

We all sat on the floor in the dark room, listening to my uncle talk to my parents in a hushed voice: “Brother and sister, please take my words very seriously. They have already prepared everything to torture brother at tomorrow’s struggle session. The only way to save yourself is to escape before daybreak, otherwise they will kill you. I finally decided to come tell you under risk of my own life. Now there are only a few hours left, so please hurry up and get ready to escape somewhere far away!”

After this, my uncle left quietly, and we hastily moved into action. My mom used the only two pounds of bread flour we had for the entire year to bake a few Chinese pancakes for my father to take along. I sat on the floor, helping my mom by keeping the wooden fire going.

We got my father ready to leave in about 30 minutes. All our family members, including my little sister and my grandmother, were crying as we said goodbye and watched my father gradually vanish into the darkness of the blizzardy night.

With just a few pancakes and 50 yuan my uncle had given him, my father left home in that cold winter night of 1968 to escape being beaten to death at the struggle session set up for the following evening.

End of part I of II of Yukui Liu’s account. Part II will appear shortly, and be linked to this article.