TORONTO—Canadian cybercrime researchers have uncovered a vast online web of espionage based and controlled from China and mainly targeting the Indian government.

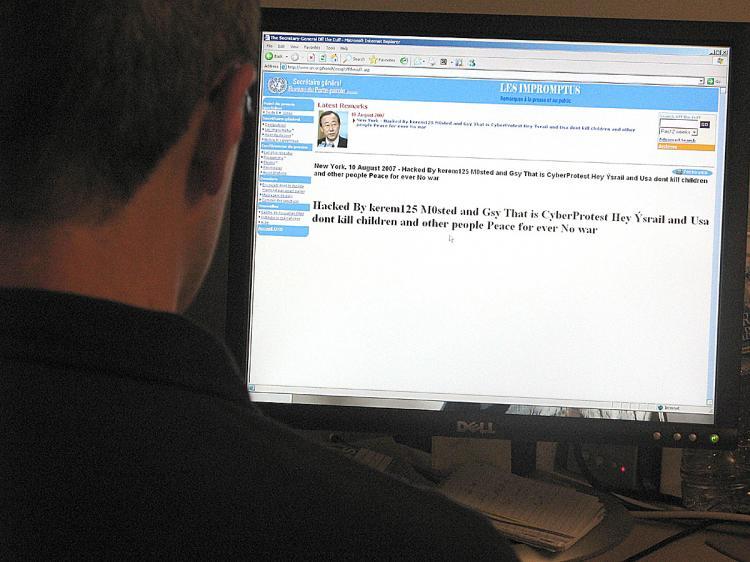

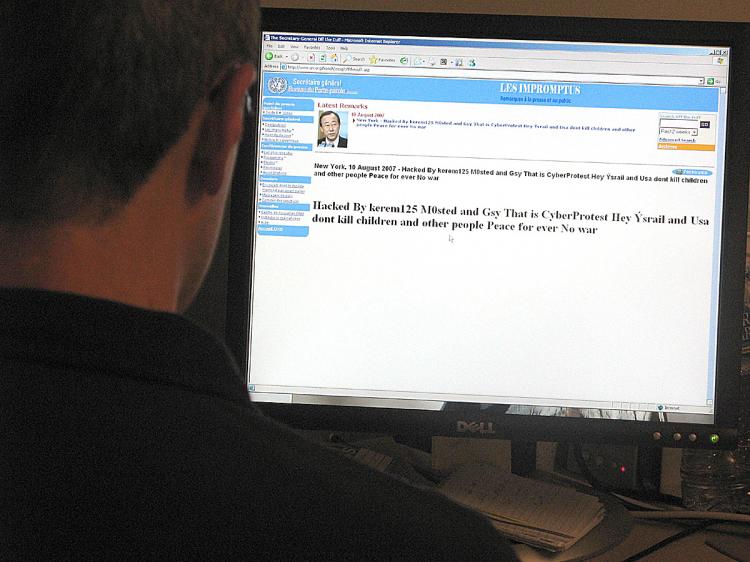

Researchers at the Information Warfare Monitor and the Shadowserver Foundation released a report Tuesday documenting a complex espionage “ecosystem” using social networking sites and free Web hosting to steal sensitive documents from India, the United Nations, and the offices of the Dalai Lama, as well as other countries. The core servers controlling the espionage are based in Sichuan Province’s capital city, Chengdu, China.

There exists a “subterranean ecosystem to cyberspace within which criminal and espionage networks thrive” said Ron Deiber director of Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs, in a press release.

Citizen Lab, one of the member groups of Information Warfare Monitor, worked previously with the Tibetan government and community in exile uncovering GhostNet, an espionage network targeting Tibetans.

Now Citizen Lab is releasing their documentation of a similar and overlapping espionage network entitled Shadow. Shadow was found to be targeting the Indian government, but the group also found information the network had extracted information from the offices of the Dalai Lama.

Shadow makes use of a network of computers compromised by malware—software designed to take over, monitor, or otherwise harm computers, often without the owner’s knowledge. The network of computers communicate with core control servers in China by sending information to a specific e-mail account or through free Web-hosting services and social networking sites, as directed by the malware.

The report highlights what the researchers call a “generational shift” in malware networks. They say that once simple networks are becoming complex systems moving from criminal exploitation to political, military, and intelligence-focused espionage.

As targets expanded to include political, military, or intelligence information the researchers found that the hackers were still somewhat indiscriminate about what information they took—taking sensitive personal and financial information as well.

“We see criminal networks increasingly compromising sensitive targets and stealing sensitive information in addition to typical things that they’re interested in like credit card numbers and bank account numbers,” said Deiber speaking at a press conference Tuesday.

According to the report the attackers also systematically harvested sensitive personal, financial, and business information belonging to Indian officials.

Through the Shadow network hackers were able to access files in the upper levels of the Indian national security establishment as well as information from the offices of the Dalai Lama. Documents belonging to the Indian government recovered by the researchers included ones classified as “secret,” “restricted,” or “confidential.”

Although the group found the control servers of the network are based in China they were unable to make a direct link between the attackers and the Chinese regime.

Speaking at the press conference, Nart Villeneuve, chief security officer at the SecDev Group commented that both the hacking community and the Chinese government are not unified monolithic actors. The government and Communist Party have factions, some may be working with hackers, some not: “It’s very unclear what the relationship [is] between any of these particular hacking groups and the Chinese government. We didn’t find any hard evidence that links these hacks to the Chinese government.”

Villeneuve says that these attacks work by exploiting the human element. The goal of the attackers is to get the victim to open an infected attachment or click on a URL.

“They will either use compelling newsworthy themes or in some cases, they’ll use very specific information from a previous attack,” said Villeneuve.

He says to watch out for attachments containing pdf’s, word documents, PowerPoints, and Zip files. The infected files will compromise your computer bringing it under the attacker’s control. They will then be able to send documents from your computer to other locations.

“Anti-virus systems as they stand at this moment are not terribly effective with these kinds of attacks where the attacker is specifically attacking any given organization, members of the government or corporations,” said Greg Walton, a SecDev Group associate and editor of Information Warfare Monitor Web site.

Walton advises people to use external channels of communication or digital signatures when in doubt about a particular attached file.

For the average consumer, “stick to the basics,” says Villeneuve. He says to keep systems like Adobe Reader up to date and keep an eye out for suspicious e-mails.

“We feel very strongly that it’s an area of urgent redress”, said Deiber. “Right now governments around the world are aggressively adopting techniques to fight and win wars in cyberspace.”

Deiber also mentioned that the group intends to hold a global security cyber summit at the University of Toronto in the fall, bringing together policymakers from the global community in order to share resources and in hopes of building best practices in a domain currently lacking norms.

Researchers at the Information Warfare Monitor and the Shadowserver Foundation released a report Tuesday documenting a complex espionage “ecosystem” using social networking sites and free Web hosting to steal sensitive documents from India, the United Nations, and the offices of the Dalai Lama, as well as other countries. The core servers controlling the espionage are based in Sichuan Province’s capital city, Chengdu, China.

There exists a “subterranean ecosystem to cyberspace within which criminal and espionage networks thrive” said Ron Deiber director of Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs, in a press release.

Citizen Lab, one of the member groups of Information Warfare Monitor, worked previously with the Tibetan government and community in exile uncovering GhostNet, an espionage network targeting Tibetans.

Now Citizen Lab is releasing their documentation of a similar and overlapping espionage network entitled Shadow. Shadow was found to be targeting the Indian government, but the group also found information the network had extracted information from the offices of the Dalai Lama.

Shadow makes use of a network of computers compromised by malware—software designed to take over, monitor, or otherwise harm computers, often without the owner’s knowledge. The network of computers communicate with core control servers in China by sending information to a specific e-mail account or through free Web-hosting services and social networking sites, as directed by the malware.

The report highlights what the researchers call a “generational shift” in malware networks. They say that once simple networks are becoming complex systems moving from criminal exploitation to political, military, and intelligence-focused espionage.

As targets expanded to include political, military, or intelligence information the researchers found that the hackers were still somewhat indiscriminate about what information they took—taking sensitive personal and financial information as well.

“We see criminal networks increasingly compromising sensitive targets and stealing sensitive information in addition to typical things that they’re interested in like credit card numbers and bank account numbers,” said Deiber speaking at a press conference Tuesday.

According to the report the attackers also systematically harvested sensitive personal, financial, and business information belonging to Indian officials.

Through the Shadow network hackers were able to access files in the upper levels of the Indian national security establishment as well as information from the offices of the Dalai Lama. Documents belonging to the Indian government recovered by the researchers included ones classified as “secret,” “restricted,” or “confidential.”

Although the group found the control servers of the network are based in China they were unable to make a direct link between the attackers and the Chinese regime.

Speaking at the press conference, Nart Villeneuve, chief security officer at the SecDev Group commented that both the hacking community and the Chinese government are not unified monolithic actors. The government and Communist Party have factions, some may be working with hackers, some not: “It’s very unclear what the relationship [is] between any of these particular hacking groups and the Chinese government. We didn’t find any hard evidence that links these hacks to the Chinese government.”

Protecting Against Attacks

Villeneuve says that these attacks work by exploiting the human element. The goal of the attackers is to get the victim to open an infected attachment or click on a URL.

“They will either use compelling newsworthy themes or in some cases, they’ll use very specific information from a previous attack,” said Villeneuve.

He says to watch out for attachments containing pdf’s, word documents, PowerPoints, and Zip files. The infected files will compromise your computer bringing it under the attacker’s control. They will then be able to send documents from your computer to other locations.

“Anti-virus systems as they stand at this moment are not terribly effective with these kinds of attacks where the attacker is specifically attacking any given organization, members of the government or corporations,” said Greg Walton, a SecDev Group associate and editor of Information Warfare Monitor Web site.

Walton advises people to use external channels of communication or digital signatures when in doubt about a particular attached file.

For the average consumer, “stick to the basics,” says Villeneuve. He says to keep systems like Adobe Reader up to date and keep an eye out for suspicious e-mails.

“We feel very strongly that it’s an area of urgent redress”, said Deiber. “Right now governments around the world are aggressively adopting techniques to fight and win wars in cyberspace.”

Deiber also mentioned that the group intends to hold a global security cyber summit at the University of Toronto in the fall, bringing together policymakers from the global community in order to share resources and in hopes of building best practices in a domain currently lacking norms.