Koko is a store of unique distinction with its classic feminine styles in luminous colors and sublime textures. The items are made by Dutch-born designer Marianne Kooimans, and her clothes and shoes are a precious reminder of craftsmanship in a world of mass production and corporate globalization.

Kooimans is not only preserving the ideals of Old World refinement and artistry, but in a real and tangible way, she is truly preserving vanishing textile techniques.

I met Kooimans in her airy Abbot Kinney store, the efforts of husband and business partner Steve Wood.

She was sporting one of her own black and white skirts, a solid black long-sleeved V-neck, patterned black stockings, shoes that are sold at Koko’s, and a thick pearl necklace. She tells me that she prefers simple clothes she can easily work in. A slim woman, Kooimans wears signature dramatic red lipstick and has bobbed hair that she twists up.

Though she is striking in appearance, her manner is gentle as she tells me the genesis of her work.

After graduating from her studies at the Art Academy of Rotterdam in fashion and monumental design in Holland, Kooimans worked primarily for performers, creating high-tech costumes in plastics.

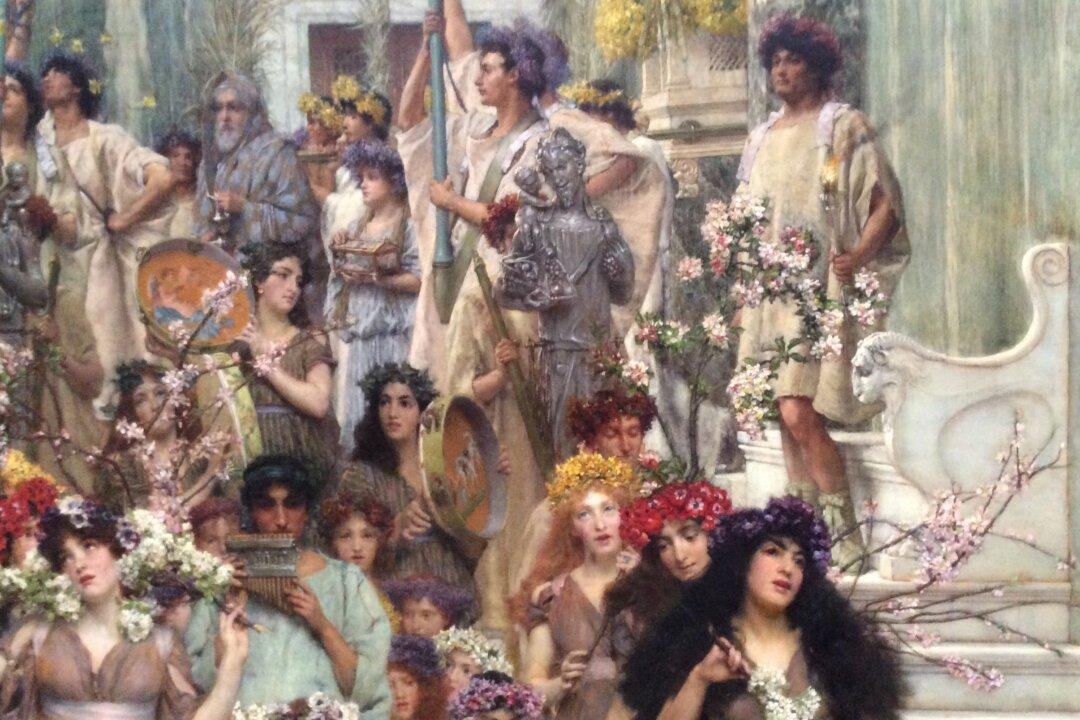

Cambodia was different. “I fell in love with the silks there,” says Kooimans of the Cambodians’ unique method of weaving. She traveled between the United States and Cambodia, working with a small clothing company developing and designing textiles.

Having found a “krama,” a scarf, in one particular style, Kooimans carried it around to various Cambodian villages, like in an Asian folktale, in search of anyone who could reproduce it.

She leads me to the hanging apparel, educating me on silk as she shows me an example of the unique fabric, “a cross between organza and soft silk,” she explains, “soft and crisp.”

“In Cambodia, people work from home and have looms in their houses,” she explains. “Unlike China, it is all handmade.”

Also contributing to the silk’s unique quality and properties is the fact that it is made on bamboo looms, unlike in China where metal combs are used. The industrial metal combs create a uniform texture, whereas the irregular Cambodian method allows for more beauty of texture.

Reviving the quickly vanishing silk weaving techniques and fabrics, “I made a market for it, and made sure people were trained to make this fabric,” she said.

Back in the United States, Kooimans began to design her own clothes, which became more complicated as her skills expanded.

Now, once the silk is made, Cambodian silk is sent to Italy for embroidery. The embellished silk is then sent back to Cambodia to be cut and sewn into Kooimans’ elegant designs.

The sewing is primarily done by two families, but Kooimans is very hands-on, preparing patterns and cutting material herself. “It’s collaboration,” she acknowledges.

Kooimans is not only preserving the ideals of Old World refinement and artistry, but in a real and tangible way, she is truly preserving vanishing textile techniques.

I met Kooimans in her airy Abbot Kinney store, the efforts of husband and business partner Steve Wood.

She was sporting one of her own black and white skirts, a solid black long-sleeved V-neck, patterned black stockings, shoes that are sold at Koko’s, and a thick pearl necklace. She tells me that she prefers simple clothes she can easily work in. A slim woman, Kooimans wears signature dramatic red lipstick and has bobbed hair that she twists up.

Though she is striking in appearance, her manner is gentle as she tells me the genesis of her work.

After graduating from her studies at the Art Academy of Rotterdam in fashion and monumental design in Holland, Kooimans worked primarily for performers, creating high-tech costumes in plastics.

Cambodian Silks

A textile competition in Japan brought her to Asia. “I was very attracted to that part of the world,” she said.Cambodia was different. “I fell in love with the silks there,” says Kooimans of the Cambodians’ unique method of weaving. She traveled between the United States and Cambodia, working with a small clothing company developing and designing textiles.

Having found a “krama,” a scarf, in one particular style, Kooimans carried it around to various Cambodian villages, like in an Asian folktale, in search of anyone who could reproduce it.

She leads me to the hanging apparel, educating me on silk as she shows me an example of the unique fabric, “a cross between organza and soft silk,” she explains, “soft and crisp.”

“In Cambodia, people work from home and have looms in their houses,” she explains. “Unlike China, it is all handmade.”

Also contributing to the silk’s unique quality and properties is the fact that it is made on bamboo looms, unlike in China where metal combs are used. The industrial metal combs create a uniform texture, whereas the irregular Cambodian method allows for more beauty of texture.

Reviving the quickly vanishing silk weaving techniques and fabrics, “I made a market for it, and made sure people were trained to make this fabric,” she said.

Back in the United States, Kooimans began to design her own clothes, which became more complicated as her skills expanded.

Now, once the silk is made, Cambodian silk is sent to Italy for embroidery. The embellished silk is then sent back to Cambodia to be cut and sewn into Kooimans’ elegant designs.

The sewing is primarily done by two families, but Kooimans is very hands-on, preparing patterns and cutting material herself. “It’s collaboration,” she acknowledges.