Chinese netizens believe that the Chinese state has proscribed the books of over 30 scholars and writers, and statements by publishing houses reported by Chinese web portals support their belief. The banned list includes many liberal writers—some have supported the pro-democracy Occupy Central movement in Hong Kong, some have criticized China’s political system, and some have promoted constitutionalism and the rule of law.

Since Oct. 11, many Chinese lawyers, writers, and citizens have passed around on the Internet the news that the State Administration of Press, Publication, Film and Television has banned books from the famous Chinese historian Yu Ying-shih and the Taiwanese writer Giddens Ko.

Also said to be banned are books by the Chinese poet and novelist Zheng Shiping (known by his pen name Yefu), Chinese economist Mao Yushi, Chinese law professor Zhang Qianfan, Hong Kong writer and TV host Leung Man-tao, columnist Xu Zhiyuan, and so on, comprising a list of more than 30 people.

A photo of a notification ordering all retailers and stores to immediately take the books written by Yu Ying-shih off the shelves that was issued by Shanghai People’s Publishing House on Oct. 10 was posted on Sina Weibo by a user named “erheixifu012."

Other than this photo, whose veracity can’t be confirmed, there has been no paper trail documenting the ban and no official confirmation of it. However, on Oct. 13 several large mainland web portals, including Sina.com, reported that many publishing houses have confirmed the rumor. These reports were subsequently taken off the websites, although the headlines can be seen on Google.

Acting on news of the ban, the popular shopping network China Dangdang quickly created a new page with the theme “The books that you won’t be able to buy soon,” listing books written by the writers believed to be banned.

On top of the web page, it says, “Different people like different books, but there are some books that even if you don’t want to read them now, you should buy them first, because soon there will be nowhere to buy them.”

Chinese activists and citizens have complained loudly at the news of the book ban. Beijing activist Hu Jia told U.S.-based Sound of Hope radio, “A writer’s publications are a writer’s income, especially in such a big market as mainland China. If one’s books are banned to sell in mainland, it’s a very realistic pressure … [The Chinese Communist Party] not dealing with over 30 people is on one hand a revenge to those 30 some people, on the other hand it is to frighten other scholars and writers.”

Chinese law professor Fan Zhongxin posted on his verified Sina Weibo account, a twitter-like platform, “[Chinese] authorities frequently give orders by phone calls or oral notification, but publicly damage citizens’ constitutional rights, such as the ban of the books of Yu Ying-shih and Zhang Qianfan.

“They don’t leave any printed evidence, and they don’t dare to issue a document,” Hu said. “Such a method could even make Emperor Qin [famed as a tyrant in ancient China] and Adolf Hitler ashamed. Facing such obvious violations of law, one can’t even find evidence to bring a lawsuit. Is there still rule of law? ”

Facing condemnation on the Chinese internet of the book banning, Chinese Communist Party mouthpiece Global Times published an opinion article that said books that are constantly against the system are impossible to maintain in any kind of society. The dissidents need to clearly understand this “iron law,” wrote Global Times.

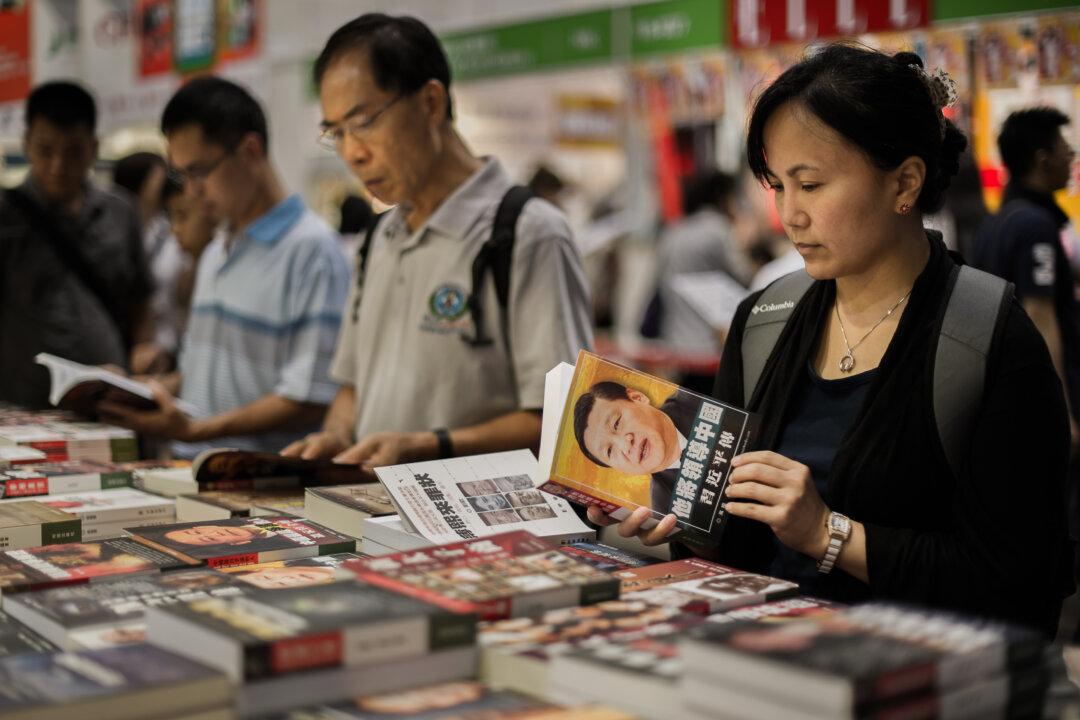

The news of the book ban has motivated some Chinese to read them.

“I’ve never read Yu Ying-shih’s books, but I’ve heard that his books are banned, which stimulated my curiosity to read them,” remarked the user “Law and Order” on the microblog platform Weibo (The remarks were deleted on China’s Internet but retrieved through the service Freeweibo.com, which archives deleted messages). “I’ve always believed that in this country, a book that can be banned is mostly a good book and worth reading.”

“Banning speech is the best promotion for an author. When you are not certain about something, the word ‘banned’ can make its truth clear to you.”