Ten thousand years from now, human historians—or alien ones—may view the current wave of biodiversity loss and extinctions as concurrent with the Pleistocene extinction that saw everything from mammoths to woolly rhinos to saber-toothed cats wiped out. At that time, peaking around 11,000 years ago, many scientists argue that sophisticated, migrating human hunters killed off the majority of the world’s big species in a great wave, leading to cascading impacts on top predators and global environments. According to a new paper today in Science Advances history may be repeating itself or, more simply, this ‘overkill’ may simply be ongoing.

“The wave of species extinctions that obliterated 80 percent of the Pleistocene megaherbivores (over 1,000 kilograms) on planet Earth appears to be continuing today in Africa and Southeast Asia,” the 16 scientists write in the paper. “ The very recent extinctions of Africa’s western black rhinoceros and Vietnam’s Javan rhinoceros are sober reminders of this long-term trend.”

Looking at the surviving megaherbivores (or big plant-eating mammals), the paper found that 60 percent are currently threatened with extinction and 58 percent have declining populations. And just like how early humans hunted big mammals to extinction, the team found that hunting was still one of the biggest threats to today’s megaherbivores.

“I expected that habitat change would be the main factor causing the endangerment of large herbivores,” said lead author William Ripple with Oregon State University. “But surprisingly, the results show that the two main factors in herbivore declines are hunting by humans and habitat change. They are twin threats.”

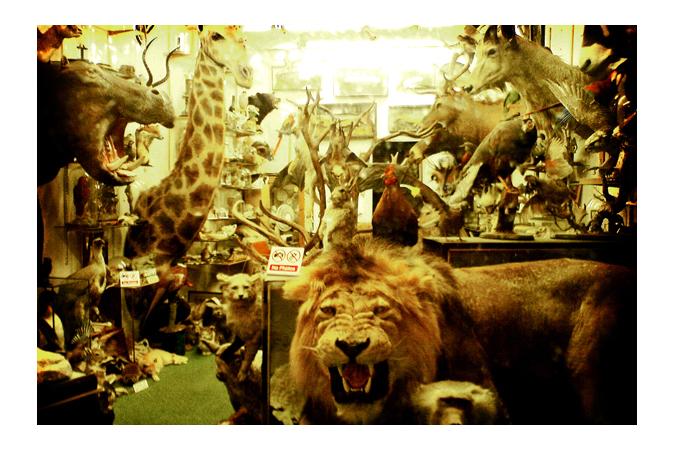

Ripple’s study defined megaherbivores as those over 100 kilograms (or 220 pounds) which means 74 currently-identified species, including elephants, rhinos, gorillas, giraffe and okapi, horses, hippos, tapirs, camels, as well as a number of the biggest deer, antelope, andbovine, and six species of wild pigs.

The bulk of these endangered megaherbivores are found in Asia and Africa. In fact, all 19 of the megaherbivores in Southeast Asia are threatened with extinction. Of Africa’s 32 megaherbivores, 12 are threatened. South America is only home to five megaherbivores, but four of these are threatened with extinction. Only one species in Europe is threatened (the European bison) and none in North America.

The study follows similar research on top predators last year, also headed by Ripple, that found 77 percent of the world’s 31 biggest carnivores were in decline.

Overkill

It’s well-reported that rhinos and elephants are suffering from a poaching crisis that has put nearly all of their members at risk, but hunting is also impacting a wide variety of other megaherbivores, including everything from wild pigs to giraffe and hippos to tapirs.

“Extensive overhunting for meat across much of the developing world is likely the most important factor in the decline of the largest terrestrial herbivores,” the researchers write. “Slow reproduction makes large herbivores particularly vulnerable to overhunting. The largest- and slowest-to-reproduce species typically vanish first, and as they disappear, hunters turn to smaller and more fecund species, a cascading process that has likely been repeated for thousands of years.”

In Southeast Asia, overhunting and poaching has led to the so-called empty forests syndrome, where whole forests have been virtually emptied of large-bodied mammals and birds. But, the researchers now argue that this idea could be expanded toward “empty landscapes,” where large herbivores are wiped out to feed rising demand for bushmeat and traditional medicine.

Of course, hunting isn’t the only threat. Habitat loss is the other big player and, for some species, eclipses hunting. Looking at one third of the megaherbivores, the researchers found that species on average had lost 81 percent of their historical range. And many of the world’s megaherbivores are increasingly competing with humankind’s favorite herbivores: cattle, goats, or sheep. According to the paper, livestock production tripled from 1980 to 2002 in the developing world.

“There are an estimated 3.6 billion ruminant livestock on Earth today, and about 25 million have been added to the planet every year...for the last 50 years,” the researchers write.

But, according to the authors, the underlying drivers behind megaherbivore loss is the same as biodiversity loss in general.

“The ultimate forces behind declining large mammal populations are a rising human population and increasing per capita resource consumption.”

Roles: from birth to death

The world’s biggest species, not surprisingly, play a number of big—and vital—roles in their respective ecosystems. They disperse seeds far-and-wide (some of which can only be dispersed by big mammals), create open areas in forests, maintain grasslands, decrease the length and intensity of fires through heavy browsing, and when they die they provide food for the world’s favorite top predators and the lesser-adored, but just as important, scavengers. Even the leftovers are important.

“Carcasses...add a variety of nutrients to the soil such as calcium, with effects that can persist several years after the death of the animal,” the researchers write.

Although the interaction between big herbivores and predators or scavengers is straightfoward, the researchers have also found an astounding number of links between megaherbivores and less obvious species.

“Large herbivores interact with a suite of small animals including birds, insects, rodents, lizards, and others,” the write. “For example, several fish species feed on flesh wounds of hippopotamus, and the dung of Asian elephants may be used by amphibians as daytime refuge...Bison wallows support amphibians and birds by creating ephemeral pools, and bison grazing may facilitate habitat for prairie dogs and pocket gophers. Oxpeckers depend on the large herbivores for their diet of ectoparasites, and blood-sucking insects such as tsetse flies largely depend on herbivores for food.”

Big herbivores are also key for tourism. Think: white rhinos in South Africa, gorillas in Rwanda, elephants in India, and bison in Poland.

“Charismatic large herbivores are important flagship fauna that draw many tourists to protected areas, especially when they are sympatric with large carnivores,” the researchers write.

Happy herbivores

The current state of megaherbivores doesn’t mean they are doomed to extinction. The last hundred-plus years comes with several stories of conservationists saving charismatic plant-eating mammals from the very edge of extinction.

In 1894, there were only 40 white rhinos in the world, but today, there are around 20,000, (though these face a brutal poaching crisis). In 1900 there were only around 2,000 American bison, today 30,000 are in conservation herds and half a million on bison farms. Just after World War I, the European bison went extinct in the wild, but now there are 2,300 roaming free. Meanwhile, black rhino numbers have doubled in the past 20 years after bottoming out in the mid-1990s. And, after going extinct in the wild in the 1960s, Prezwalski’s horse is back: over 300 horses are roaming free in Mongolia today.

Such history lessons prove that big herbivores can make remarkable comebacks with concerted conservation efforts, even with just a few individuals left. Indeed, all of today’s European bison descend from just a dozen captive animals, and all of the Prezwalski’s horses stem from only 14.

But, researchers say that protecting our megaherbivores will depend on funds and efforts from the developed world.

“The world’s wealthier populations will need to provide the resources essential for ensuring the preservation of our global natural heritage of large herbivores,” they write, adding that “a sense of justice and development is essential to ensure that local populations can benefit fairly from large herbivore protection.”

In order to do this the researchers call for tackling demand of wildlife products from endangered species, expanding and connecting protected areas, switching out meat protein for plant protein, and more research on lesser-known megaherbivores. The researchers also hold up community conservation, where locals are brought in as stakeholders, as a model for moving forward.

“It is essential that local people be involved in and benefit from the management of protected areas,” they write. “Local community participation in the management of protected areas is highly correlated with protected area policy compliance.”

Finally, they say it’s time to start thinking beyond the popular, well-known megaherbivores.

“We advocate for a global government-funded scheme for rare large herbivores beyond elephants and rhinoceros, as well as the establishment of a nongovernmental organization that focuses exclusively on rare large herbivores, like what the Arcus Foundation does for apes or what Panthera does for large cats,” the researchers write.

Citations:

- William J. Ripple, Thomas M. Newsome, Christopher Wolf, Rodolfo Dirzo, Kristoffer T. Everatt, Mauro Galetti, Matt W. Hayward, Graham I. H. Kerley, Taal Levi, Peter A. Lindsey, David W. Macdonald, Yadvinder Malhi, Luke E. Painter, Christopher J. Sandom, John Terborgh, Blaire Van Valkenburgh. 2015. Collapse of the world’s largest herbivores. Science Advances.

This article was written by Jeremy Hance, a contributing writer for news.mongabay.com. This article was republished with permission, original article here.