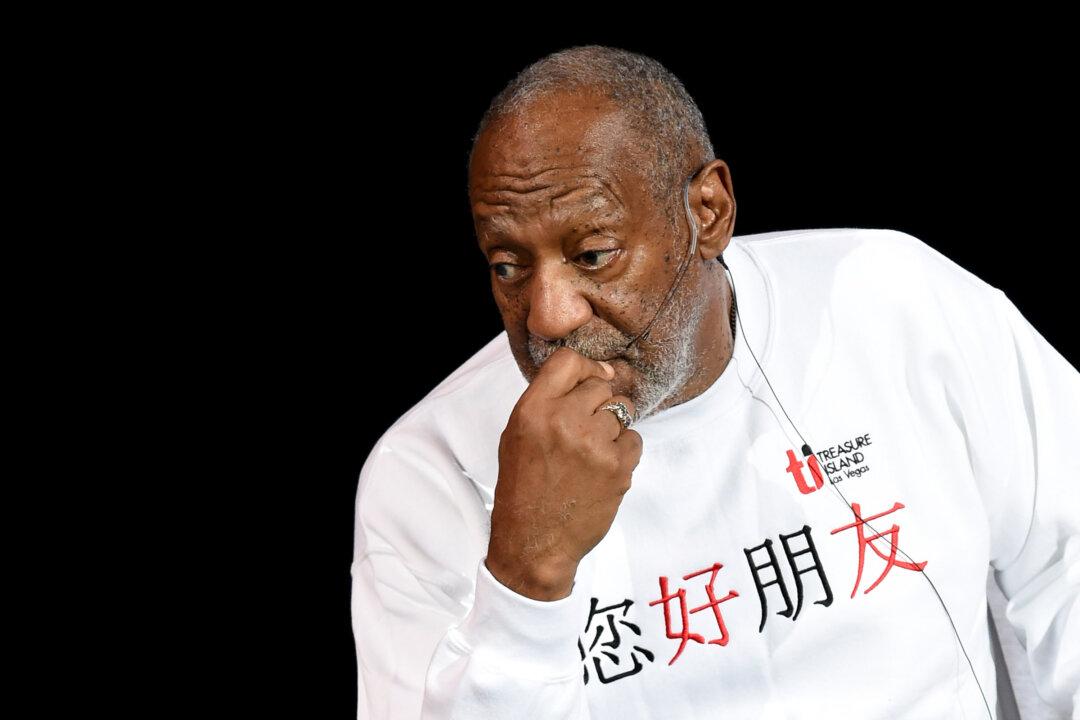

In the awful narrative around the allegations of sexual assault and rape made against iconic American entertainer Bill Cosby, a major theme has been the perceived failure of the media to challenge him on his alleged crimes over the 40 years the offences were claimed to have taken place.

In a revealing article in the New York Times, journalist David Carr writes of his own interview with Cosby in 2011. Admitting that he knew about the allegations of drugging women and sexual assaults, Carr states that he looked away when he accepted the job, knowing that he should have instead refused it: “My job as a journalist was to turn down that assignment,” he wrote. In doing the interview and not confronting Cosby, Carr felt that he, among others, was “letting down the women who were brave enough to speak out publicly against a powerful entertainer.”

Another journalist, Ta-Nahesi Coates, wrote about the time he spent in 2006–2007 following Cosby around the U.S. while the comedian addressed the state of morality in black America. In the article that resulted from the research, Coates stated that though he made a “brief and limp mention of the accusations against Cosby… There was no opinion offered on the rape accusations.” This despite, as he admitted, “I believed that Bill Cosby was a rapist.”

That these two men admit contrition for omission is something to be applauded—but is it possible that we should have a certain amount of sympathy for their actions? As Coates says, lacking physical evidence, adjudicating rape accusations is a murky business for journalists.

Let us not underestimate the power of Cosby, too. We should not forget that he was probably without equal in terms of the status he occupied. As head of the Huxtable family in the phenomenally successful Cosby Show, which ran from 1984 to 1992, Cosby was instrumental in the portrayal of a successful black family whose comedic highs and lows were not reliant upon stereotype and prejudice. For Carr, the prestige of Cosby was such that he was “never just an entertainer, but a signal tower of moral rectitude.”

If Carr had broached the subject of his alleged crimes there is no doubt that his time with Cosby would have ended and would have found himself at the mercy of his “ferocious lawyers and stalwart enablers.”

The threat of legal action is very real for those in the mainstream media and remember this very crucial point: in the eyes of the law Cosby is innocent. He has not been charged, let alone convicted for sexual crimes or otherwise.

Remember too that journalists exist within society and not apart from it. We might expect a reporter charged with interviewing Cosby to bring up the allegations, but would we, in a similar situation, risk the threat of interview termination, legal action, career meltdown and the wrath of an editor without a story who has sent us to interview the world’s most famous entertainer?

To be clear, I request a little understanding of the constraints under which journalists operate and not to excuse the behavior of the mainstream media. In general I agree with the view of Bill Wyman who wrote in the Columbian Journalism Review that traditional media culture tends to venerate celebrity to the degree that “the narrative of the star is so powerful that digressions that clash with it are discarded.”

That said, the admissions of these two journalists should not lead to the belief that the media ignored the claims around Cosby, either. As Tom Stocca illustrates, in 2005 a woman who claimed she was drugged and raped by Cosby was interviewed on the NBC Today program The same year, FOX News reported Beth Ferrier came forward to allege Cosby drugged and sexually assaulted her, months after she ended a consensual affair with him. In 2006, People Magazine ran the Cosby under Fire story, concerned with Andrea Constand who claimed Cosby had drugged and sexually assaulted her in his Pennsylvania mansion in 2004.

That the scandal has regained currency now is largely due to the comments of U.S. stand-up Hannibal Buress, who on stage in Cosby’s hometown of Philadelphia last month said:

Bill Cosby has the f@#$%‘ smuggest old black man public persona that I hate… He gets on TV, ’Pull your pants up black people, I was on TV in the 80s! I can talk down to you because I had a successful sitcom!' Yeah, but you rape women, Bill Cosby, so turn the crazy down a couple notches.

News of the routine spread within hours and it has now been viewed more than 91,000 times on YouTube.

These events demonstrate the power of social media to spread old news to new audiences. Politico journalists Anna Palmer and Darren Samuelsohn argue that part of the reason the past does well on social media is because users tend to be younger and not familiar with the first cycle of a particular story. It is also a useful forum for the outraged and previously unheard to voice their discontent. In this sense, behavior which was once considered socially unremarkable can now be “held to current moral standards.”

It is highly unlikely that Cosby will face criminal charges now. What is becoming increasingly apparent though is that this fresh controversy has killed Cosby’s career and demolished his reputation. Sensitive to the furor and conscious of public mood, NBC has cancelled the development of his new project. Netflix has postponed a broadcast of his live show and Viacom’s cable and satellite station, TV land, has stopped repeating the Cosby show in the week it was due to have been part of a Thanksgiving sitcom marathon.

What’s the upshot of all this? Bringing down Cosby—something the mainstream media couldn’t manage in decades—took the internet just over a week. And that, surely, is of great importance.

John Jewell is director of undergraduate studies at the School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies at Cardiff University in the U.K. This article was originally published on The Conversation.