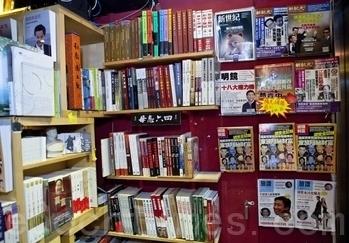

Some tourists from mainland China go to Hong Kong to stock up on Australian milk powder. Others make their way to Russell Street, to the People’s Recreation Community bookstore. They come for the banned books.

The New York Times recently published an article about the thriving trade at the Russell Street shop and at other Hong Kong booksellers in books the Chinese Communist Party’s censors have proscribed.

Among the eager customers are Chinese officials. The New York Times quotes Ho Pin, “an exiled Chinese journalist who runs Mirror Books, a company based in New York that publishes muckraking books and magazines in Chinese,” as saying that visiting Chinese officials often buy the books as gifts for fellow officials.

“In the past, you’d give a mayor a bottle of liquor. But that’s nothing these days, and so is a carton of cigarettes. But if you give him one of our books or magazines, he’ll be very happy,” Ho Pin told the New York Times.

Paul Tang, the proprietor of the People’s Recreation Community bookstore, says his business thrives in part because of the patronage of officials.

They fear using the Internet to look at banned material or lack the skill to evade censorship, Mr. Tang told the New York Times. They prefer the reassuring weight of a hard copy, contraband volume in their hands.

Treasures

Of course, mainland China’s society is distorted. In more normal countries, a trip to the bookstore is not usually freighted with such significance. For a long time, though, some Chinese citizens have treated banned books like special treasures—and they have been right to do so.

People heard that I owned a copy of The Private Life of Chairman Mao. Published in 1994, before the Internet, this book, written by Mao’s personal physician, told of the real Mao: his sexual escapades, orchestration of political events, and manipulation of others.

Everyone tried to please me—people who knew me and people who didn’t know me—just so that they could get their hands on this book.

Two years later, this book was finally returned to me with a cover that had been taped and strengthened beyond recognition.

A prosecutor in Beijing told me in a phone call when registering to borrow the book that he had read some pages of it in a confiscated underground printing factory. He sighed that just those scattered fragments were “enough to overturn my view of the world.”

This prosecutor expressed what all of us wanted in seeking out this book and other books about Mao’s hideousness or about other power-mad officials or events the Party did not want talked about.

The prosecutor wanted a chance to come to grips with the world as it is. He didn’t have any illusion of being free inside China but he wanted a chance not to be made a fool of by the Party’s propaganda.

Survival

The motives of the officials who frequent Paul Tang’s shop are different. They want to survive.

One staple of Tang’s trade are exposés that retail the latest gossip about top Party officials.

Titles such as Sex Report on the Party Elite or Scandal of the Standing Committee Seven purport to give intimate details of the lives of the powerful not available in the carefully sanitized pages of People’s Daily.

Such gossip may help a local official as he seeks to understand the shifts in power taking place beneath the murky surface of political events.

But the anxieties of today’s Party officials go far beyond navigating the Party’s treacherous politics.

The No. 1 seller in Paul Tang’s shop is 2014: The Great Collapse.

Published on Jan. 1, 2013, the book tells a fictional story of the CCP’s Emergency Response Team submitting a secret report to the Politburo Standing Committee warning of the downfall of the party in 2014.

The top-secret report describes a terrifying crackup ready to hit the Chinese regime: The economic system collapses, businesses go bankrupt, widespread theft breaks out, mass protests take to the streets, and revolutionaries appear. In the book, the Standing Committee holds a conference in response to this report, but the discussions reveal even more shocking details that show the inevitability of the CCP’s downfall.

This fiction is all too real to China’s officials. Hong Kong’s Cheng Ming magazine reported in its April issue that the Politburo Standing Committee with the Politburo held meetings on March 12 and 13 where Party leader Xi Jinping spoke of the solemnness and urgency of the Party facing its challenges. According to Cheng Ming, Xi Jinping claimed that the next two years will determine whether the CCP lives or dies.

As the Party goes, so go the Party officials. They read the Great Collapse and see an all too real future. Anxious and frightened, they beat a path to Russell Street to take the temperature of the crisis.

They read the compilations of gossip, the stories of political intrigue, and the fact-based analyses from Taiwan, and they try to calculate the odds. How will they save themselves, and when do they need to make their move?

That the officials are sorting through Paul Tang’s wares at all only confirms how desperate these rulers of China are.

Translation by Sunny Chao, Virginia Wu, and Irene Luo. Written in English by Stephen Gregory.