Rio Tinto Trial a Cause for Concern in Australia

The trial against Australian citizen and former Rio Tinto executive Stern Hu has concluded.

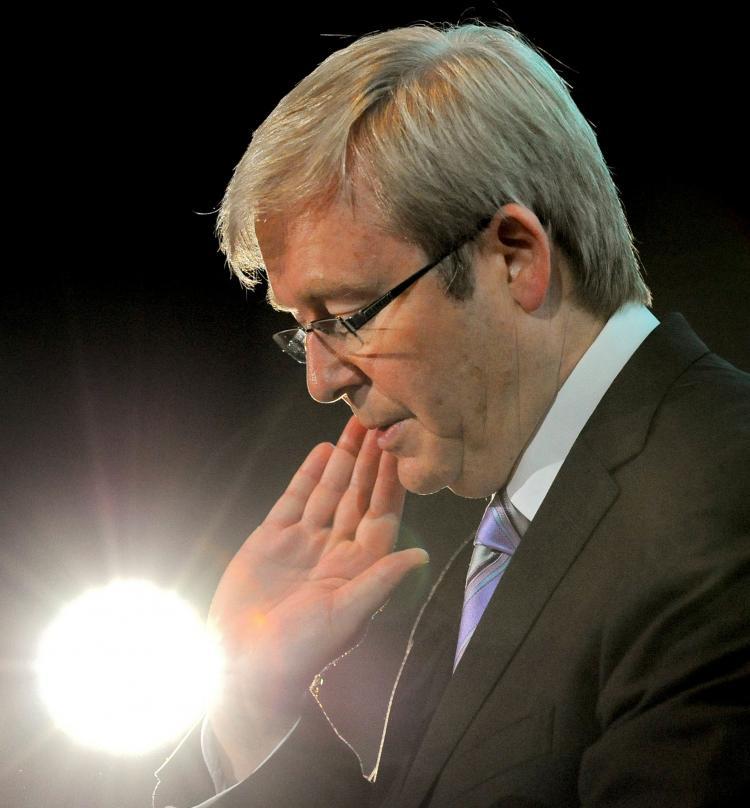

Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd speaks at a gathering in Melbourne on March 30. He said the trial in China of four employees of the Australian-British mining giant Rio Tinto, over charges of bribery and stealing commercial secrets, left 'serious unanswered questions.' William West/AFP/Getty Images

|Updated: