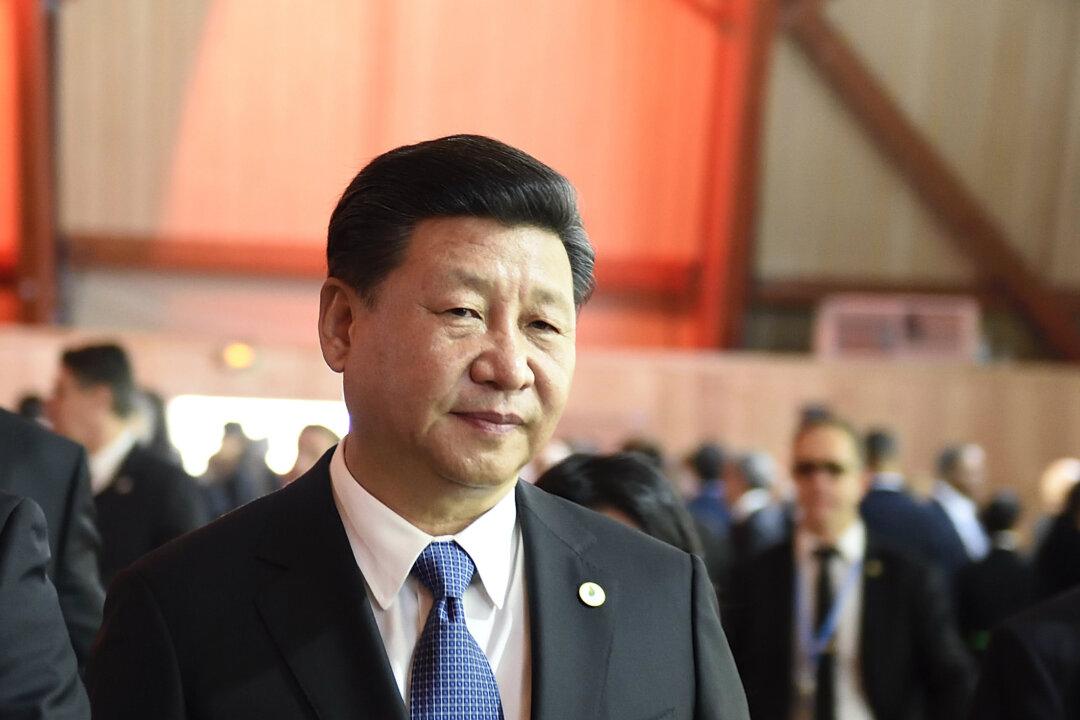

In 2015, Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping’s very public efforts to root out corruption in the Party have continued relentlessly.

Foremost, three elite cadres retired from top leadership were expelled from the Party, and one was handed a life sentence. The Party’s internal disciplinary body purged top executives in prominent state-owned enterprises, and doubled the companies to be probed. And for the first time since Xi’s anti-corruption campaign began in 2013, a Party official from every single one of China’s 31 provinces has been investigated.

Xi Jinping is playing for big stakes. His “anti-corruption” campaign is meant to give him a free hand by uprooting the faction loyal to former Party leader Jiang Zemin. In 2016, the big question will be what Xi will choose to do with this freedom.

No Show and Tell

The muted denouncement of former high-ranking officials Zhou Yongkang, Ling Jihua, and Guo Boxiong this year has perhaps loudly signaled Xi’s greater ambitions.

The trial of Zhou, the Chinese regime’s former security czar, had been highly anticipated since he was investigated in July 2014. It thus came as a shock when footage of Zhou wearing a black trench coat, his white-haired head bowed during a closed-door trial, was aired with no prior fanfare on state television in June.