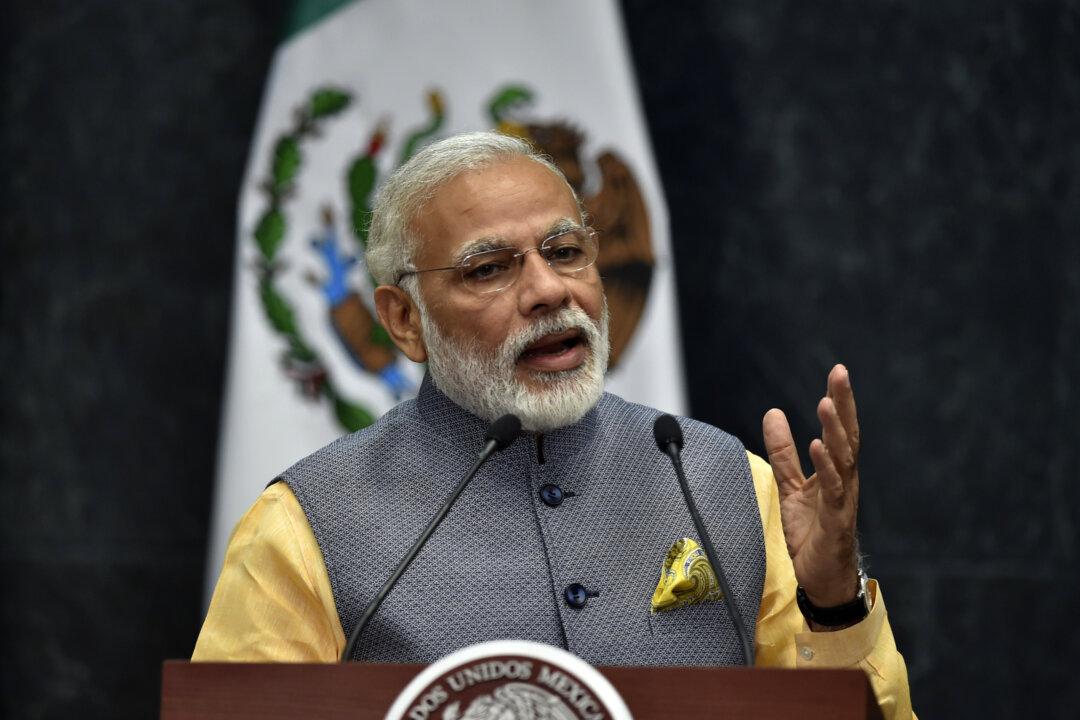

LONDON—India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been a once-in-a-generation opportunity for reorienting ties with the United States. Modi is undertaking his fourth visit to the United States since taking office and his last engagement with the Obama administration for President Barack Obama, strengthening U.S.-India ties is an achievement in an otherwise underwhelming foreign policy track record, and the two men have developed personal rapport. Both would like to institutionalize this rapport so that long-term sustainable outcomes can be achieved.

Even as Modi reinforces his credentials as the politician best placed to move forward not only Indian economic reforms but also Indo-U.S. ties, he must address concerns in the U.S. polity about India’s record on religious tolerance as well as on economic issues such as protection of intellectual property and high tariffs. There is a strong bipartisan commitment in Washington for the issue and Modi cannot let that waiver.

At a time when the U.S. Congress is tightening the screws on military aid to Pakistan and has effectively blocked the funding of F-16 fighter sale, the U.S. House of Representatives in May approved a bipartisan legislative move to strengthen defense ties with India, bringing the nation on par with NATO allies in so far as defense equipment sales and technology transfer are concerned. The amendment on security cooperation asks the U.S. government to enhance India’s military capabilities and promote co-development opportunities and calls upon New Delhi to move towards combined military planning with the United States for missions of mutual interest. A similar bill has also been introduced in the Senate.

Indo-U.S. defense ties have soared under the Modi government powered by defense trade between the two worth $14 billion in 2015. The two nations are collaborating on joint projects with a significant strategic imprint such as aircraft carrier and jet engine designs. Joint exercises are routine with new areas such as anti-submarine warfare being explored. India has yet to agree to the U.S. request for joint patrolling of the sea lanes, though after years of wrangling, in April agreed in principle to open up its military bases to the United States. This pact is expected to be signed during Modi’s U.S. visit. Such sharing and exchanging of logistics would allow the two naval forces to refuel and re-provision expeditiously.