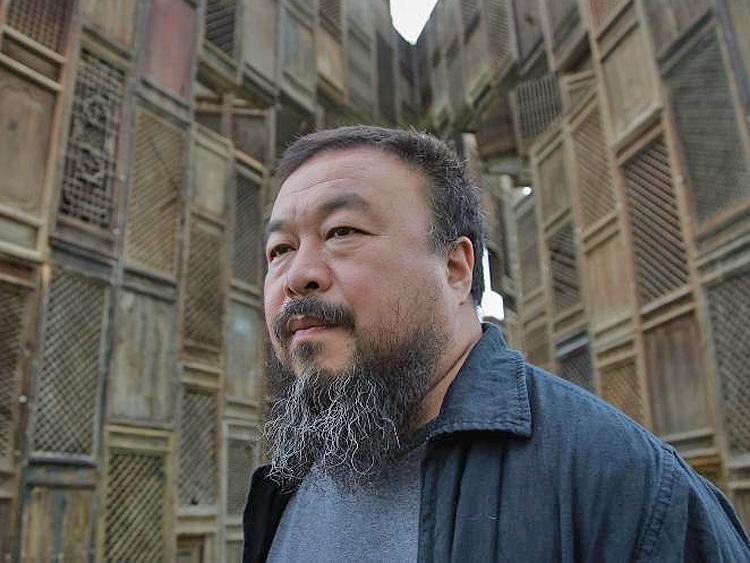

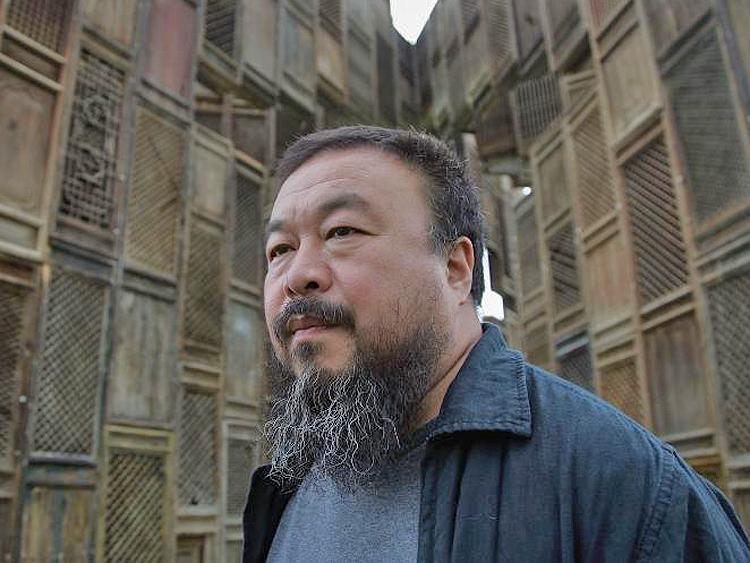

The wife of prominent Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei, Lu Qing, was allowed to meet her husband under tense and highly controlled conditions on Sunday. Both Lu Qing and Ai’s sister, Gao Ge, gave interviews with foreign media saying that he was in good health but that they know little more.

Authorities arrived at Lu Qing’s home unannounced on May 15 and told her that she was permitted a visit. They escorted her to “an investigative office,” according to Liu Yanping, who works at Ai Weiwei’s art studio, writing on her microblog.

There, a Domestic Security officer demanded that the conversation be limited to Ai’s health—the status of the investigation into Ai’s alleged “economic crimes” or whether Ai made forced confessions under torture, were not to be mentioned. They met for no more than 15 minutes, according to Liu’s post.

In an interview with the Associated Press, his wife described Ai as having “puffy eyes,” and appearing in a state of inner conflict. “He has changed. His mood and demeanor are so different from the simple and spontaneous Ai Weiwei I know,” she said.

One man scribbled notes while another kept an eye on the prisoner, Lu Qing said to AP.

Ai’s sister, Gao Ge, confirmed the meeting with BBC, Deutsche Welle and Radio Free Asia (RFA) and said that despite the circumstances Ai was in good health.

Gao Ge said the meeting was not held where Ai is being held captive, and the family does not know where he is being detained. The purpose of the meeting, Gao Ge said, was to let Ai’s family and outside world know that he is “healthy.”

Ai Weiwei told his wife during the meeting that he was not tortured, as had been previously reported. Some saw in this the design behind the meeting, and even a “deal” between the authorities and the family.

The website of the “Initiators of the Chinese Jasmine Revolution” carried a commentary by a veteran of Chinese journalism, identified only as “Mr. Yan.”

The analysis sought to problematize the statement by Ai’s wife that the artist was not tortured in custody. “If there was no torture, then why doesn’t CCTV or BJTV show an interview of Ai Weiwei?” Yan asked, referring to China Central Television and Beijing Television, both of which are state mouthpieces.

“There has been torture for sure. Otherwise, Ai would not have given in and Ai’s family would not change their strong stance,” he said. He suggested that by emphasizing Ai’s health and saying that he was not tortured, there is a stronger chance that he’ll be released.

Ai Weiwei has become one of China’s foremost public figures because of his bold criticism of the ruling Communist Party and the authorities’ heavy-handed response. He was disappeared on April 3 and has been held incommunicado until this meeting. He has not been formally arrested or charged with any crime, though some weeks after his abduction from the Beijing Airport he was denounced in CCP publications and accused of “economic crimes.”

Ai’s treatment happens during a period that many observers describe as the most repressive in a decade. Tolerance of public dissent against the CCP has reached an all-time low, and the means used to seek reprisals against dissidents have become increasingly bold in the face of international criticism, including a wide range of extralegal measures.

Authorities arrived at Lu Qing’s home unannounced on May 15 and told her that she was permitted a visit. They escorted her to “an investigative office,” according to Liu Yanping, who works at Ai Weiwei’s art studio, writing on her microblog.

There, a Domestic Security officer demanded that the conversation be limited to Ai’s health—the status of the investigation into Ai’s alleged “economic crimes” or whether Ai made forced confessions under torture, were not to be mentioned. They met for no more than 15 minutes, according to Liu’s post.

In an interview with the Associated Press, his wife described Ai as having “puffy eyes,” and appearing in a state of inner conflict. “He has changed. His mood and demeanor are so different from the simple and spontaneous Ai Weiwei I know,” she said.

One man scribbled notes while another kept an eye on the prisoner, Lu Qing said to AP.

Ai’s sister, Gao Ge, confirmed the meeting with BBC, Deutsche Welle and Radio Free Asia (RFA) and said that despite the circumstances Ai was in good health.

Gao Ge said the meeting was not held where Ai is being held captive, and the family does not know where he is being detained. The purpose of the meeting, Gao Ge said, was to let Ai’s family and outside world know that he is “healthy.”

Ai Weiwei told his wife during the meeting that he was not tortured, as had been previously reported. Some saw in this the design behind the meeting, and even a “deal” between the authorities and the family.

The website of the “Initiators of the Chinese Jasmine Revolution” carried a commentary by a veteran of Chinese journalism, identified only as “Mr. Yan.”

The analysis sought to problematize the statement by Ai’s wife that the artist was not tortured in custody. “If there was no torture, then why doesn’t CCTV or BJTV show an interview of Ai Weiwei?” Yan asked, referring to China Central Television and Beijing Television, both of which are state mouthpieces.

“There has been torture for sure. Otherwise, Ai would not have given in and Ai’s family would not change their strong stance,” he said. He suggested that by emphasizing Ai’s health and saying that he was not tortured, there is a stronger chance that he’ll be released.

Ai Weiwei has become one of China’s foremost public figures because of his bold criticism of the ruling Communist Party and the authorities’ heavy-handed response. He was disappeared on April 3 and has been held incommunicado until this meeting. He has not been formally arrested or charged with any crime, though some weeks after his abduction from the Beijing Airport he was denounced in CCP publications and accused of “economic crimes.”

Ai’s treatment happens during a period that many observers describe as the most repressive in a decade. Tolerance of public dissent against the CCP has reached an all-time low, and the means used to seek reprisals against dissidents have become increasingly bold in the face of international criticism, including a wide range of extralegal measures.