Commentary

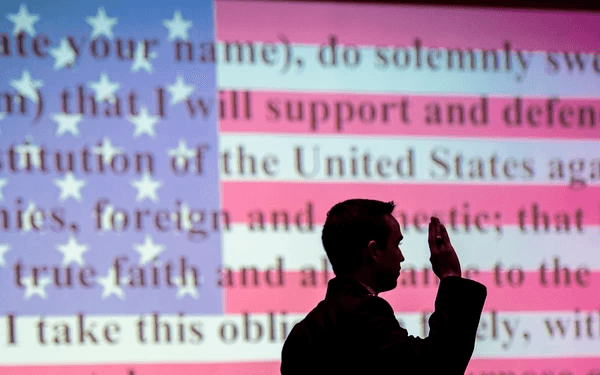

What does it mean to serve? What does it mean to be in the service of others? Is it something in us to serve? Is it a nature vs. nurture debate? Is it about a self-fulling prophecy? Is it some ego trait? Is it genuine? In contemplating the essence of service, I find myself engulfed in profound introspection, diving into its meaning and implications.