NEW YORK—Clayton Colaw, a millennial working on his master’s in sustainability at Columbia University, sees many things in the business world he thinks he can do better, especially from a leadership standpoint.

“The old adage is that the first thing a business is supposed to do is make money,” said Colaw. But that is not enough—you also have to care about people. “Sustainability is caring about making money by doing things right,” he said.

As part of his degree, the articulate 27-year-old is studying a wide range of topics, from the earth’s climate system; to sustainable finance, green energy finance, and cost-benefit analyses taking into account sustainability metrics; to the particular challenges women with children face in riding public transportation.

Studying the history of the Industrial Revolution showed him that “we are just now realizing that maybe we did it the wrong way,” he said.

Polling consistently shows that millennials (ages 18–35 years old today) are more willing than any other generation to support changes in lifestyle, politics, and business that contribute to a more sustainable world.

This is to be expected since they are the first cohort to grow up feeling threatened by climate change. What is lesser known, though, is how they are products of a carefully constructed paradigm shift within higher education that aims to transform what, and how, students learn.

It is called Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), and it is the new environmentalism, except that it goes far beyond how to take care of the natural world and mitigating greenhouse gases. It also involves far-reaching social goals like ending poverty, inequality, and gender discrimination.

Sustainability advocates are desperately hopeful that millennials will learn the skills and the kind of creative thinking they say it takes to create a more sustainable world.

While experts say the impact of the millennial value system is still small, the millennial effect will accelerate as the nation’s largest cohort matures. They will take more top leadership positions, become our elected leaders, and control trillions in generational inherited wealth.

The values they learn today will guide our tomorrow.

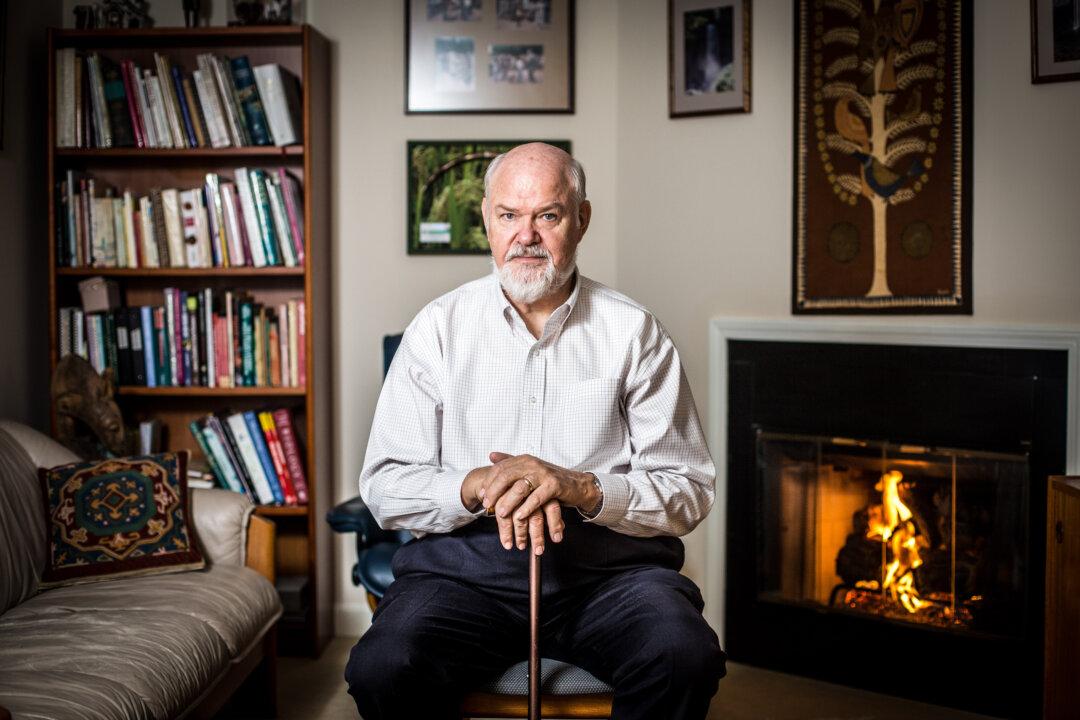

Portrait of a Generation