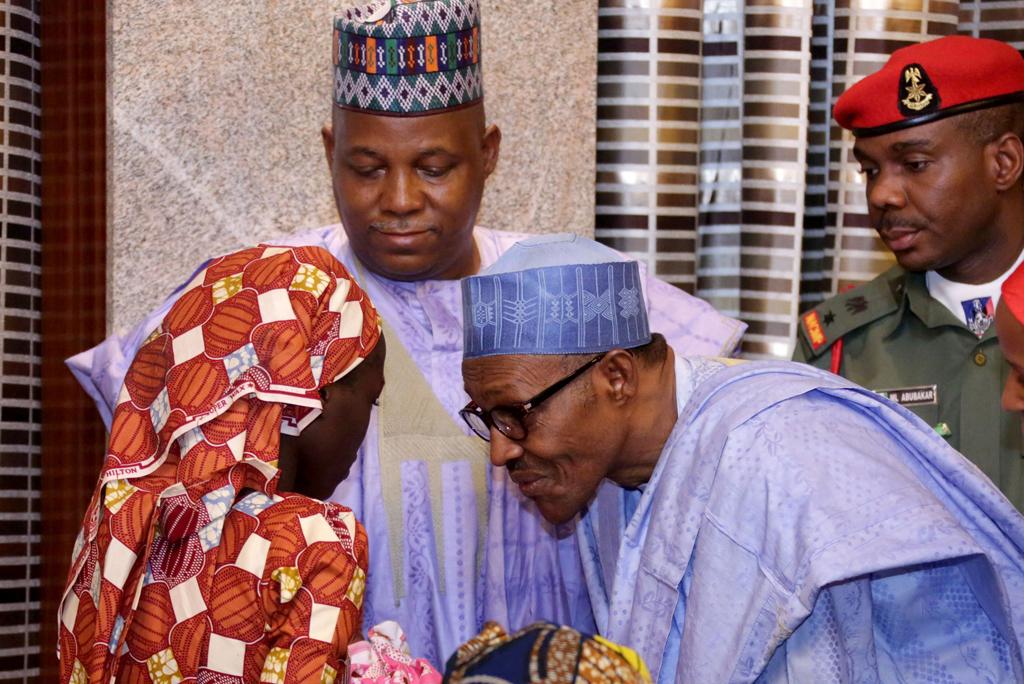

President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria has finally named his Cabinet. He was either slow, or he was very choosy, or he couldn’t find enough honest people. Certainly his 55th national anniversary speech was full of references to “lawless habits,” with particular reference to public officials.

Bold though that speech was, Buhari still has much to do—and he may not have the dependable and powerful army he needs to do it.

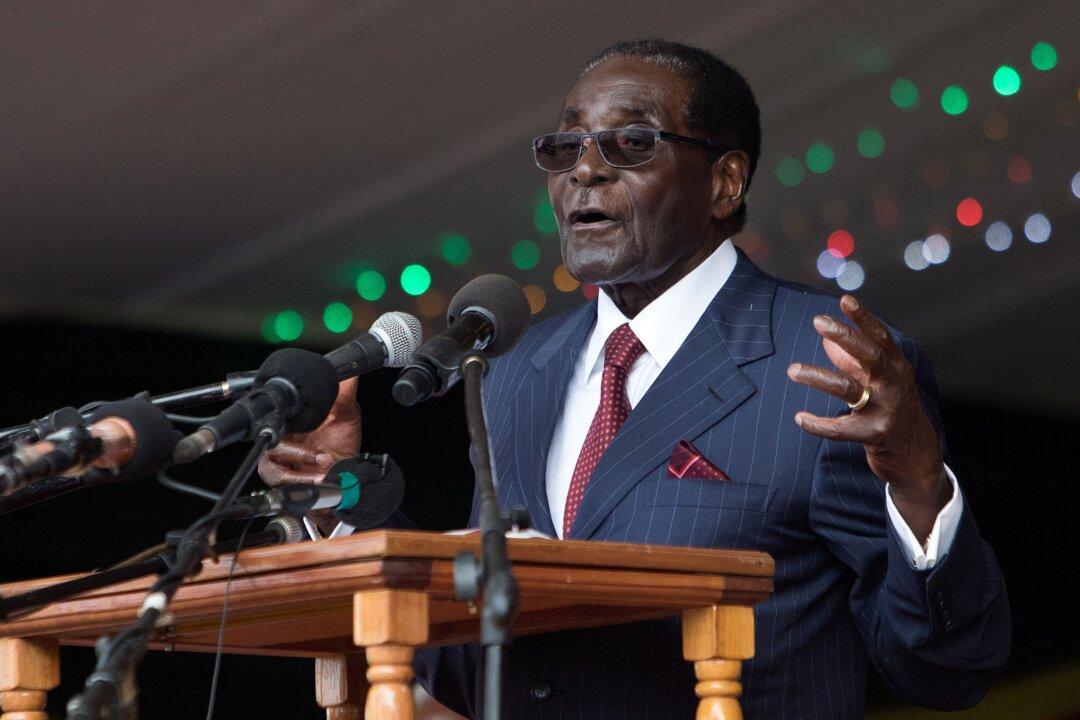

The anniversary was followed by bomb attacks on the capital, Abuja. Meanwhile senior military figures were involved both in starting and ending the coup in Burkina Faso. The army sided with the civilian administration and helped deliver the surrender of troops from the mutinous Presidential Guard.

Yet even in the torrid Burkina Faso affair there was a display of African statesmanship at its best, with a succession of presidents and the chair of the African Union for once immediately condemning the coup. Buhari played a key role here as well.