In a June 6 speech to the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen said that the U.S. economy was “now fairly close to the … goal of maximum employment.”

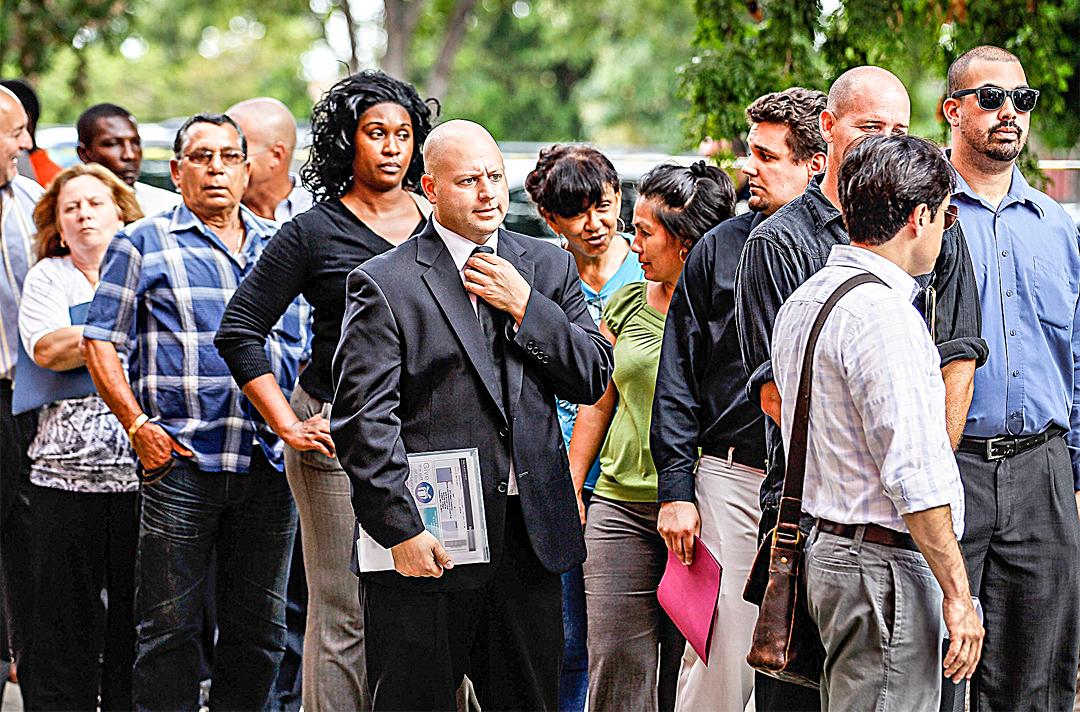

At a jobs fair held in Newburgh, New York, on Oct. 5, Drew Smith begged to differ. A former stock broker and trader for 27 years, Smith has been unemployed and looking for work for four years. The full parking lot he surveyed as he walked into the fair reinforced his belief that the unemployment rate is much higher than the official numbers.