Sponsored Content

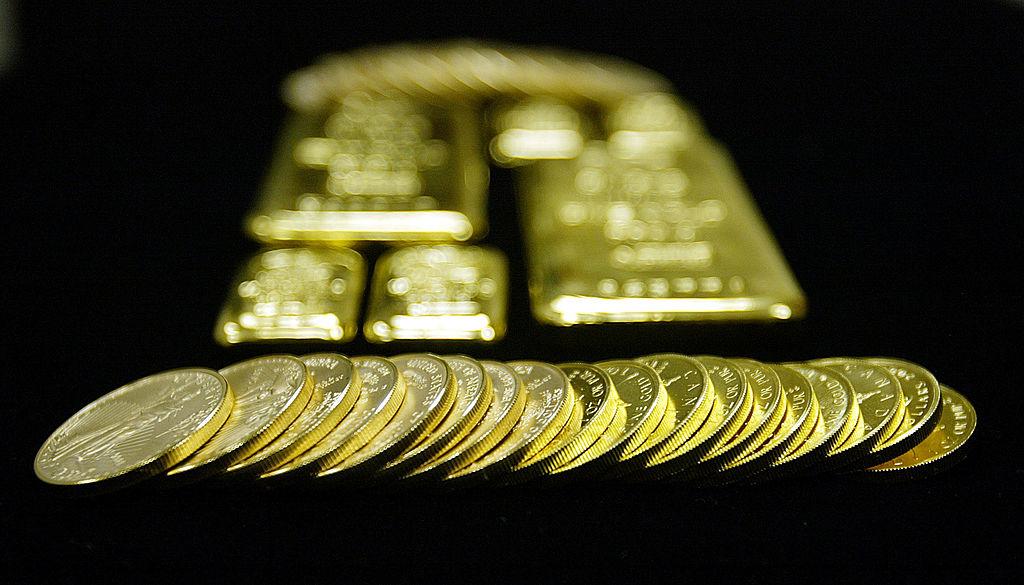

On Sept. 26, 2016, under the Obama administration, Wall Street and the U.S. banking industry expanded its powers into the precious metals sector, digitally tagging gold and silver products using standardized alphanumeric codes known as CUSIP.

CUSIP, an acronym for the Committee on Uniform Security Identification Procedures, is essentially Wall Street’s and the banking industry’s way of barcoding financial instruments.

A 55-year-old system founded by the American Bankers Association, CUSIP currently holds data on about 44 million financial products. To date, over 93 precious metals products have been coded with CUSIP identifiers.

CUSIP allows financial institutions and government to track and identify financial products, increasing security, fungibility, efficiency, and overall convenience in the trade clearance and settlement of precious metals products.

Many shortsighted sheep in the industry hail CUSIP’s entry as a “significant step” for the precious metals sector.

But no significant step comes without a major caveat: by tagging, tracking, and identifying gold and silver products, CUSIP also allows financial institutions and the government to monitor precious metals holdings and, of course, the investors who hold them.

So, in exchange for security and convenience, an investor has to give up his or her privacy of property and transaction.

But there’s a fundamental problem with this trade-off: to those investors purchasing gold and silver in order to accumulate sound money, as opposed to merely investing in a financial product for the purpose of capital appreciation, privacy is a key motivation behind the purchase.

As a means to monitor what many consider “safe haven” assets, CUSIP poses a number of secondary risks residing inconspicuously within the public narrative of safety and convenience through standardization.

- A means to encourage more efficient price manipulation: Banking institutions have been known to manipulate and suppress the price of gold and silver through precious metals derivatives—”paper gold and silver.” The capacity to manipulate prices and obfuscate the true rate of supply and demand can be strengthened by indexing actual inventories and monitoring their transactions.

- An assault on the notion of privacy, freedom, and safe-haven status: Hardly anyone would go around willingly disclosing their net worth, income, savings, and transaction habits. Most people would feel somewhat violated if an entity tracked every item they bought, where (or from whom) they bought, how often they bought certain products, and where they likely store the items they purchased. Many investors would consider their gold and silver holding to be among the most private of their private assets, considering that precious metals may constitute a significant portion of their monetary wealth. CUSIP makes such holdings and the individuals possessing them an open book, digitally accessible to institutions privy to their information.

- Countering safe haven protections in the event of a national emergency: In the event of a national emergency, such as a major financial crisis, banking collapse, or electronic infrastructure outage, a private and accessible stash of physical cash, gold and silver can serve as a practical means by which to preserve wealth and to conduct transactions. The main concern among many proponents of sound money centers on the question as to whether or not the federal government can seize gold and silver during times of a national crisis.

After all, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 6102, signed in 1933 (made under the authority of the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act) which prevented Americans from “hoarding” gold bullion, coin, or certificates beyond a certain limit was repealed in 1974 by President Gerald Ford. Since then, Ford’s bill legalized the “private ownership” of gold and other precious metals in the United States. Also note that by then, the gold standard had also been done away with three years prior, during President Richard Nixon’s administration.

So not only did gold no longer play a direct role in setting monetary policy, as the gold standard was no longer in place, but numismatic gold and silver coins weren’t even considered a “financial” instrument, relegating coins to the “collectibles” category, as it remains to this day. But the question remains: if gold and silver coins are looked upon and taxed as “collectibles,” then why the need for a CUSIP code?

Without having to answer that question, the answer to which seems rather obvious, despite its irreconcilability in terms of principle. What’s at stake is the right to private ownership amidst the possibility of a government recall. Title II of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act introduces the “Orderly Liquidation Authority,” or OLA for short, which reads: “Treasury recommends retaining OLA as an emergency tool for use under only extraordinary circumstances.”

The “extraordinary circumstances” it refers to is the event of a banking crisis or national emergency in which the financial system’s integrity needs to be upheld and maintained. This is a “bail-in,” not unlike what had happened during the Cypriot Financial Crisis of 2012-2013. Title II essentially allows the banking system to freeze your funds and take 50 percent or more in order to save the bank’s balance sheets.

Draconian measures such as this one serve as the very reason as to why prudent investors would want to accumulate private holdings of physical gold and silver. But these private holdings would easily be countered by CUSIP, which tags and tracks precious metals products and their investors. And although private holdings of precious metals aren’t currently under threat of recall nor subject to limitations, and although gold and silver coins are considered collectibles and not legal tender, laws can and do change, especially in periods of national emergency (as it did in 1933).

So, what value does CUSIP truly present to precious metals investors seeking safe haven in sound money? Is asset standardization a fair exchange for asset surveillance? Is fungibility a fair exchange for transactional freedom and privacy? Is convenience in trade clearance and settlement a good enough reason to assume the potential risk of asset recall? And if CUSIP does present a significant step in the precious metals sector, are the interests of the sector as a whole worth sacrificing the interests of the individual U.S. investor seeking a safe haven investment through sound money?

Call GSI Exchange at (833) GSI-GOLD for a copy of the CUSIP List of Precious Metals and Bank Failure Survival Guide today.

Third-party advertisements and links to other sites where goods or services are advertised aren’t endorsements or recommendations by The Epoch Times of the third-party sites, goods or services. The Epoch Times takes no responsibility for the content of the ads, promises made, or the quality/reliability of the products or services offered in all advertisements.