When John Zingsheim walked into the Aurora Medical Center in his hometown of Hartford, Wisconsin, he had no way of knowing his soon-to-be-diagnosed COVID-19 case would thrust his family into the headlines and leave his life hanging in the balance while attorneys argued over ivermectin, the treatment he requested before being placed on a ventilator.

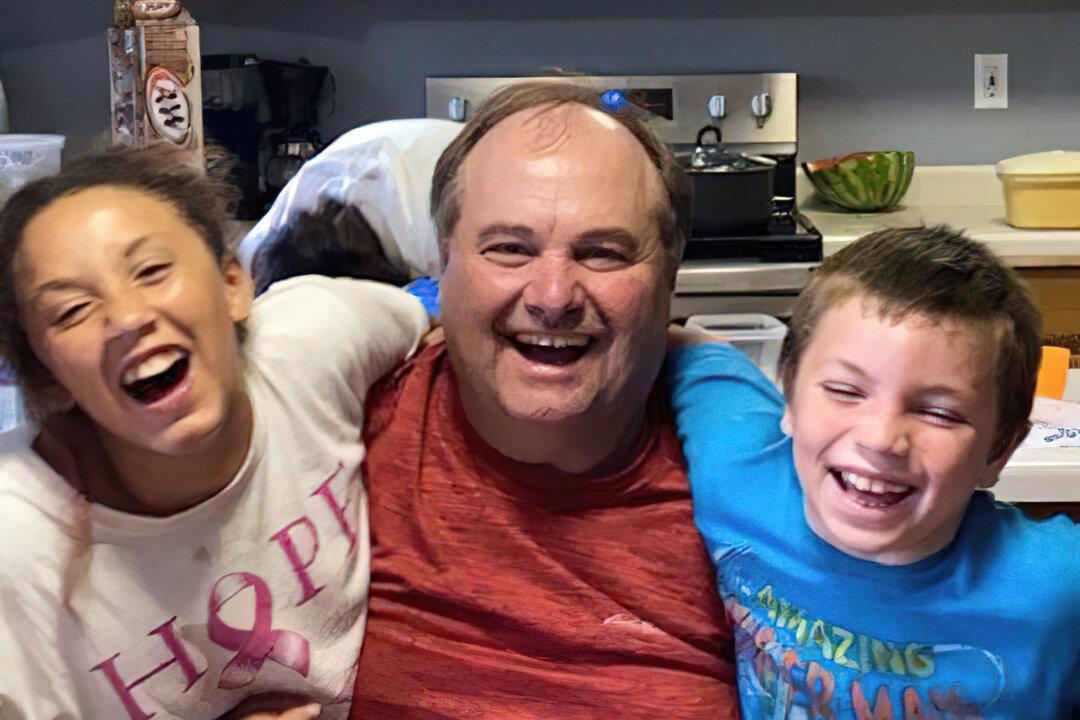

Nearly two months after being intubated, Zingsheim, 60, is hanging on—still waiting for a resolution to allow his doctor to administer treatments of ivermectin, an FDA-approved medication often used to treat parasitic infections, which more recently has been hailed in some quarters as an effective treatment for COVID-19. The two-month legal battle has left Zingsheim’s two children exasperated while their father fights for his life.