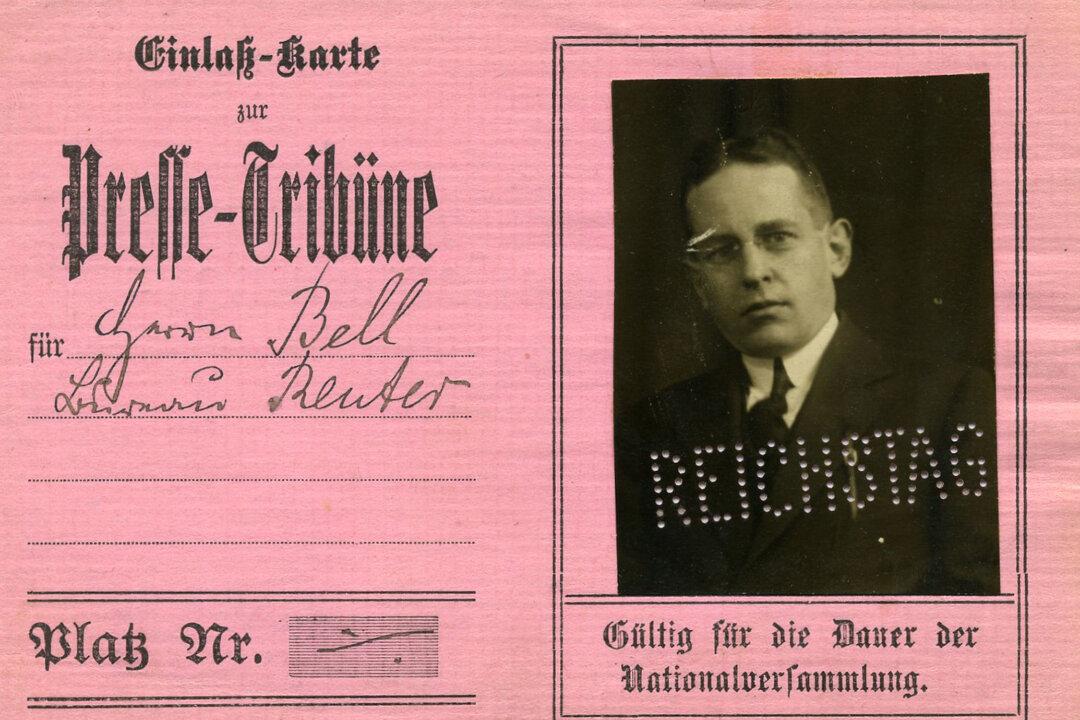

Who is the greatest spy in history? Jason Bell, professor of philosophy at the University of New Brunswick, claims he may have found him.

In his new book, “Cracking the Nazi Code: The Untold Story of Agent A12 and the Solving of the Holocaust Code,” Mr. Bell suggests that a brilliant Nova Scotian philosopher by the name of Winthrop Bell (no relation to the author) is “quite possibly history’s greatest spy.” After having read the book, there most definitely is substance to the claim.