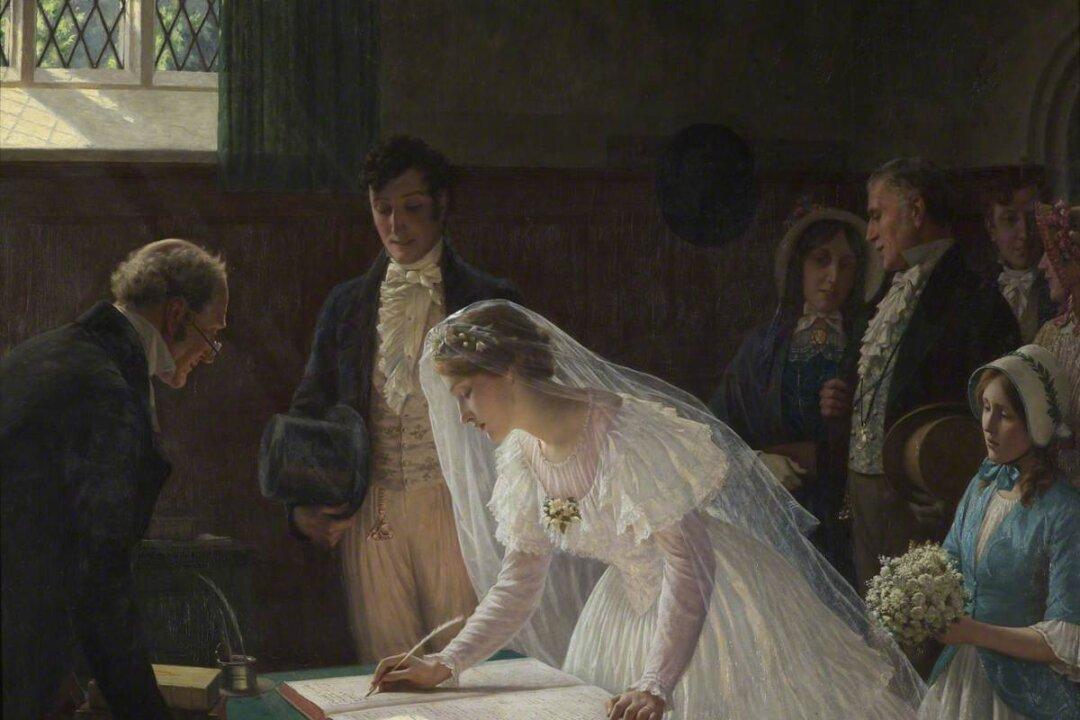

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. Sometimes this is true. A picture comes in handy when police are seeking a suspect in a crime. If all they posted on the “Most Wanted” board at the post office was a thousand words describing the ne’er-do-well, it would be significantly less likely to be noticed. The concepts of geometry would be really difficult to grasp without pictures. There is a reason Ikea assembly instructions are mainly laid out in pictures.

But, while it may be true in these cases that a picture is worth a great many words, it is not merely a matter of bookkeeping (1 picture = 1,000 words). There are times when only words will do. It is, in fact, mildly ironic that the phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words” gets across a point in seven succinct words that would be difficult to make with a picture.