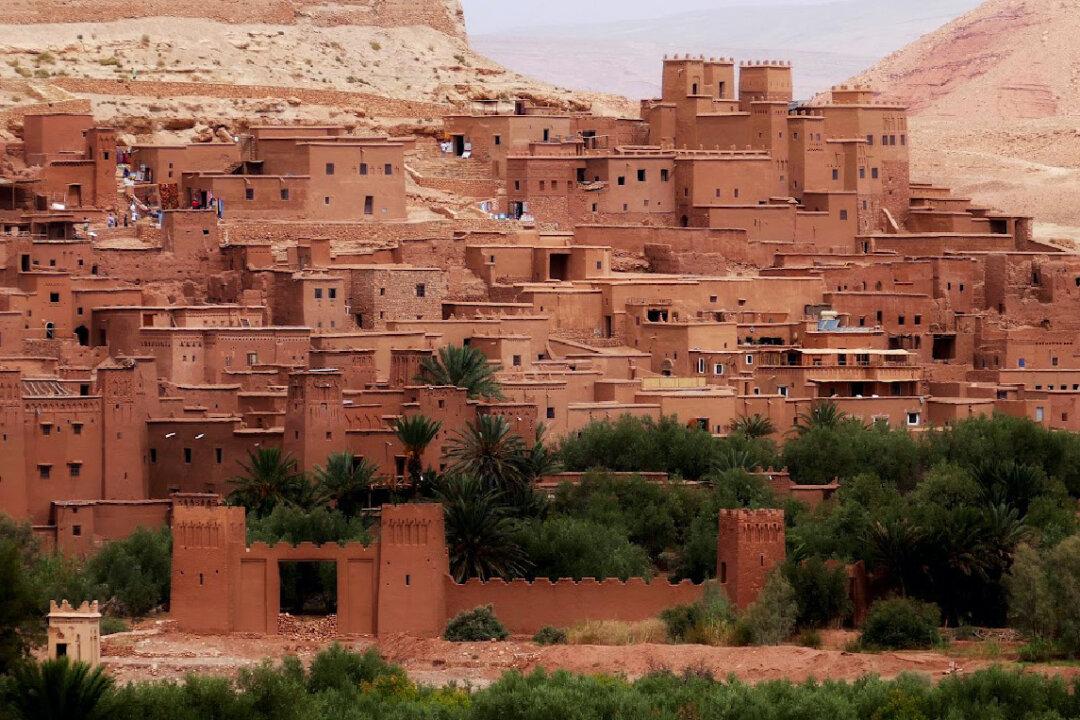

Vast parts of Morocco are covered in the sand of the Sahara and the rocks and foliage of the Atlas Mountains, but its cities are riots of color. This is especially evident in Fes, home of the famous blue pottery and a whole lot more.

And the city’s history is just as rich and vibrant. This area in the north inland part of the country was originally inhabited by indigenous Berber tribes and then founded under Idrisid rule in the eighth and ninth centuries. Waves of immigrants from Tunisia and across the Strait of Gibraltar from Portugal and Spain gave the new city the distinct Arab and Moorish characteristics it maintains to this day.