“A Faust story” describes a certain type of tale: A man sells his soul to the devil in exchange for youthful beauty, the satisfaction of lustful desires, or earthly happiness.

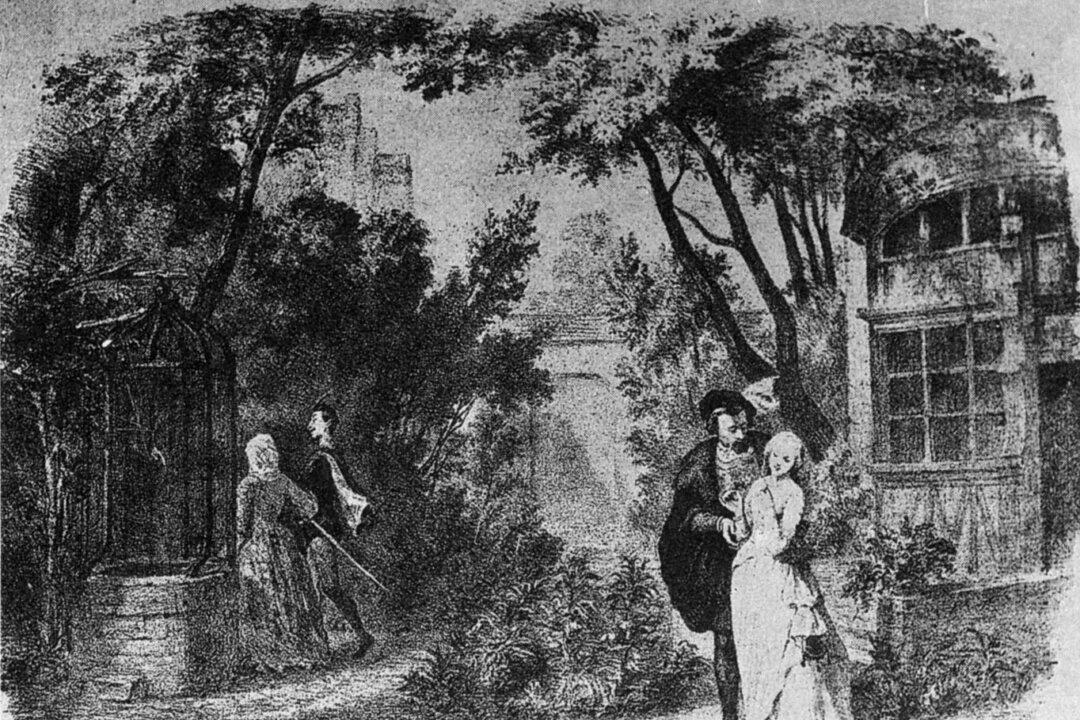

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) was inspired by centuries-old German legends to write his tragic play in two parts. “Faust,” which is occasionally called an epic poem because of its rhyming verses. It has inspired numerous musical adaptations, including several operas. Perhaps the most famous is the 1859 French opera, “Faust,” by Charles Gounod (1818–1893).