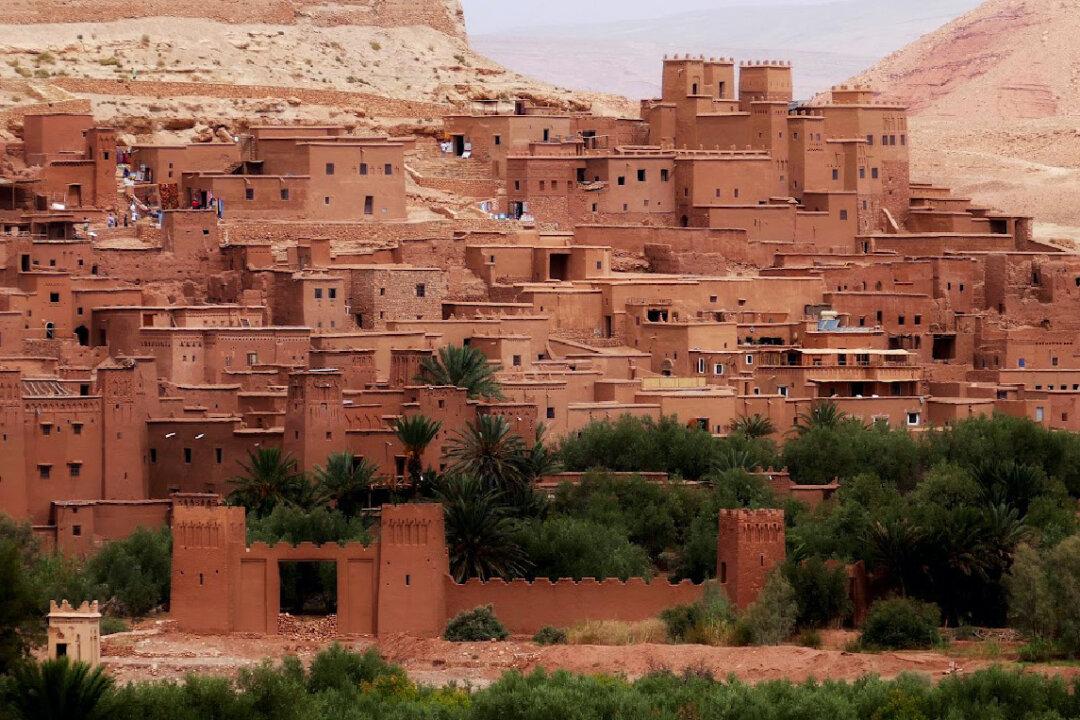

During our recent visit to Morocco, my husband and I learned that every city has a distinctive character. There was no chance we'd confuse any two when we got home and looked back on our memories. In Rabat, we saw the palace of King Mohammed VI and learned how the constitutional monarchy in this country works. In Fez, we immersed ourselves in color and art, and the best word we found to describe Marrakech, Morocco’s fourth-largest city, was “cosmopolitan.”

Our discovery of this phenomenon began the first morning we were in town with a horse-drawn carriage ride to the Majorelle Gardens, a spectacular cactus garden right in the middle of the city that is also home to 15 species of native North African birds. Designed by Jaques Majorelle during the French occupation of Morocco in 1924, the centerpiece is a cobalt-blue structure that now houses a Berber museum and gift shop. Directly adjacent is Villa Oasis, home of the late French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent and a sister museum to the one in Paris that chronicles his work. The feast that this spot provided for our senses was made even better with a stop at the cafe for a homemade lemonade that we sipped outside in the garden.