The possibility of the volcano under Yellowstone National Park erupting is a hot topic right now, especially with the recent 4.8 magnitude earthquake and videos circulating that allegedly show animals fleeing the park.

The volcano under the park is so large and has the potential to produce such a massive eruption that it’s often referred to as a supervolcano.

Earthquakes are common in the area, with between 1,000 and 2,000 quakes in the area per year due to the volcanic and tectonic nature of the region.

Rising Number of Earthquakes

But the 4.8 quake was the largest recorded since February 1980, and is part of an uplift of earthquake activity recently, caused by the upward movement of molten rock beneath the Earth’s crust, according to the U.S. Geological Service.

The number of earthquakes in the Yellowstone region has been on a trend upward for many years.

Of note is that while recent 4.8 earthquake was more intense than usual but a much more intense quake actually struck in August 1959.

The 7.5 magnitude quake hit in Montana, rattling Yellowstone and killing 28 people.

Seismologists with the University of Utah emphasized that the recent quake doesn’t signal an impending eruption of the Yellowstone supervolcano, also known as the Yellowstone Caldera.

A caldera is a volcanic crater that is caused by explosions of extraordinary violence.

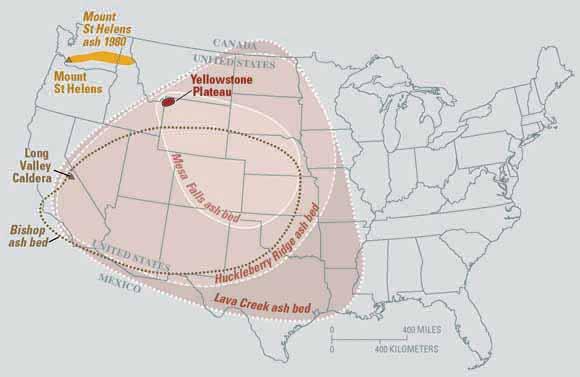

There were three explosions that formed the crater, beginning with the Huckleberry Ridge eruption 2.1 million years ago. The Mesa Falls eruption took place 1.3 million years ago. The Lava Creek eruption took place about 640,000 years ago. Several other calderas were formed during these explosions as well.

(Oregon State University)

This diagram shows how the less dense magma from reservoirs deep within the earth move upward and lift the surface of a caldera causing the faults to shift and produce earthquakes. (USGS)

The Yellowstone area has one of the most seismically active parts in the United States, this graph shows the number of volcanoes in a year and an upward trend in cumulative earthquakes in a span of almost 30 years. (USGS)

Recent earthquakes as of April 2, 2014. (Utah University)

No Eruption in Our Lifetime?

Most researchers agree that the Yellowstone supervolcano will erupt again, including Ilya Bindeman, an associate professor of geological sciences at the University of Oregon.

“Yellowstone is one of the biggest supervolcanos in the world,” he said in an analysis released by the university. “Sometimes it erupts quietly with lava flow, but once or twice every million years, it erupts very violently, forming large calderas,” which are very large craters measuring tens of kilometers in diameter.

If a huge eruption happened again, similar to three big ones over the last two million years, he says that the eruption would obliterate the surroundings within a radius of over 100 miles and cover the rest of the United States and Canada with multiple inches of ash. A volcanic event of such magnitude “hasn’t happened in modern civilization,” he says.

A diagram shows the potential range of destruction if the supervolcano was to explode. (University of Wisconsin Eau Claire)

However, Bindeman says he doesn’t think that this kind of eruption will happen anytime soon. He says it won’t happen for at least another million years.

“Our research of the pattern of such volcanism in two older, ‘complete’ caldera clusters in the wake of Yellowstone allows a prognosis that Yellowstone is on a dying cycle, rather than on a ramping up cycle,” he says.

These calderas form due to the interaction between Yellowstone’s “hot spot” (an upwelling plume of hot mantle beneath the Earth’s surface) and the North American plate, forming new magma after about a two million-year delay.

“Yellowstone is like a conveyer belt of caldera clusters,” he says. “By investigating the patterns of behavior in two previously completed caldera cycles, we can suggest that the current activity of Yellowstone is on the dying cycle.”

“It takes a long time to build magma bodies in the crust. We discovered a consistent pattern: subsequent volcanism is a combination of new magma production and the recycling of already erupted material, which includes lava and tuff,” a rock composed of consolidated volcanic ash, he said.

By comparing Yellowstone to previous completed caldera cycles, “we can detect that the Yellowstone hot spot is re-using the already erupted and buried material, rather than producing just new magma, ” he says. “Either the crust under Yellowstone is turning into hard-to-melt basalt, or because the movement of North American plate has changed the magma pluming system away from Yellowstone, or both of these reasons.”

Ilya Bindeman. (University of Oregon)

On the other hand, there’s no true way of knowing when the volcano will explode next.

The three major explosions that have happened so far--2.06 million years ago, 1.3 million years ago, and 640,000 years ago--have led some researchers to ponder whether the volcano explodes about every 700,000 years, which could include the present day.

Researchers hasten to emphasize that the series doesn’t statistically mean there’s a set pattern, though.

“One cannot present recurrence intervals based on only two values. It would be statistically meaningless ...” says the USGS in a blog post. “But for those who insist ... let’s do the arithmetic.The last eruption was 0.64 million years ago, implying that we are still about 90,000 years away from the time when we might consider calling Yellowstone overdue for another caldera- forming eruption. Nevertheless, we cannot discount the possibility of another such eruption occurring some time in the future, given Yellowstone’s volcanic history and the continued presence of magma beneath the Yellowstone caldera.”

In any case, dozens of scientists monitor the park every day and say that they’re hopeful they'll be able to alert the public if there’s an impending eruption.

“Yellowstone is monitored for signs of volcanic activity by Yellowstone Volcano Observatory scientists who detect earthquakes using seismographs and ground motion using GPS (Global Positioning System),” says the USGS. It noted that earthquakes can’t be predicted yet, but the instruments “help scientists understand the state of stress in the Earth’s crust that could trigger earthquakes as well as magma movement.”

If there is an explosion similar to the three major ones over the last 2.1 million years, author Greg Breining of “Super Volcano: The Ticking Time Bomb Beneath Yellowstone National Park” described it:

“Imagine a block of rock more than eight miles by eight miles at the base, and more than eight miles high -- a mountain far more massive than Everest -- ejected from the earth, rocketed more than twenty miles into the stratosphere, blasted down the mountainsides, pulverized, melted, and reformed as rock.”