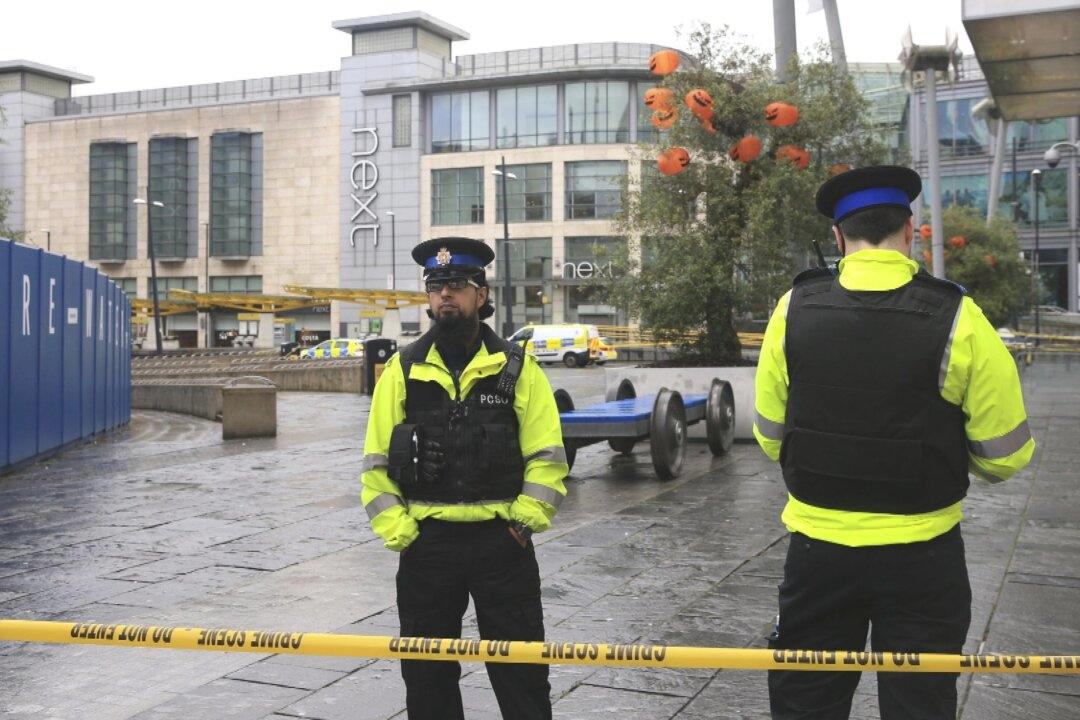

Violent and sexual offenders in England and Wales would serve more time in jail as part of sweeping sentencing changes proposed by the Ministry of Justice on Sept. 16.

Aimed at cutting crime and restoring public faith in sentencing, the “radical” justice plan would allow child-killers in England and Wales to get whole life orders (WLOs), meaning they'd never be released from prison. This would also extend to 18- to 20-year-olds if their crimes are judged serious enough.