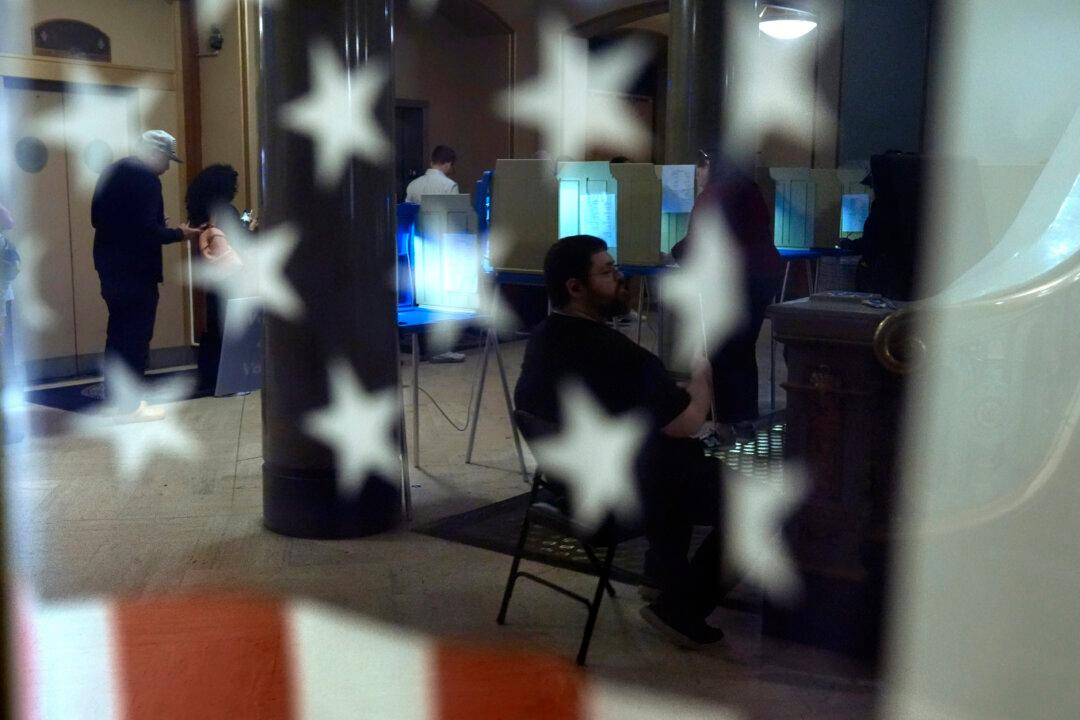

Tuesday’s vote in the United States may be dominating social media feeds, but it is just one of more than 70 national elections that will have taken place this year by the end of December.

Mauritanians went to the polls in June, the same month Mexico elected its first female president and Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared victory in India. Azerbaijanis and Indonesians voted in February. Iceland goes to the polls on Nov. 30, Ghana on Dec. 7.