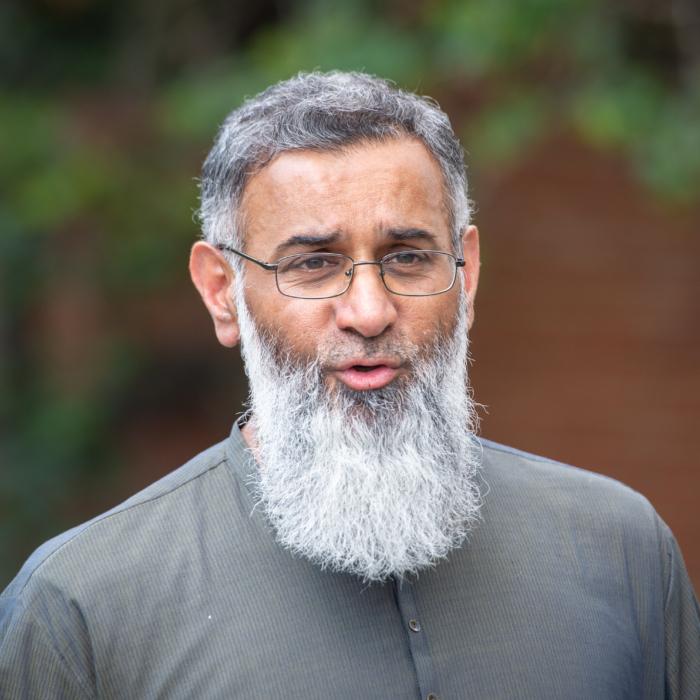

Choudary had been convicted of supporting the ISIS terrorist group but was released from prison on Oct. 19, 2018 and was on licence until July 18, 2021.

The trial heard ITS was “infiltrated” by two U.S. undercover law enforcement operatives known only by the ciphers OP488 and OP377.

One or both of them were present at a number of classes and lectures Choudary gave online and they were able to record many of them.

Prosecutor Tom Little, KC told the jury, “In the United States of America they do not have the same proscription regime; that is because of their approach to freedom of speech as Anjem Choudary was well aware.”

First Amendment Protection for Freedom of Speech

Because freedom of speech, under the First Amendment, is integral to the U.S. Constitution, it would not have been possible to prosecute Choudary in New York for what he said during those online speeches.It was never disclosed if it was the FBI or another agency that was involved, but OP488 and OP377 passed on the recordings via their superiors to the Metropolitan Police’s counter-terrorism command.

They were later played, accompanied by transcripts, to the jury at the trial of Choudary and his Canadian co-defendant Khaled Hussein.

Mr. Little pointed out to the jury how aware Choudary was of the differences in British and U.S. law.

In one conversation with ALM’s founder Omar Bakri Mohammed—who was in exile in Lebanon— on April 30, 2023, Choudary said: “If you look on the Islamic Thinkers Society err... on the net, they have a website, all of our material is there sheikh, from many, many years, you know, and they are old timers you know, from back in the days, everything err... that we published before, and alhamdulillah they’re not banned as well.”

“In America they don’t have this thing because of their freedom of speech, so it’s very beneficial for us you know,” he added.

Exceptions to First Amendment

There are some exceptions to the First Amendment.The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that obscenity and, for example, “repugnant sexual fantasies involving children” are not protected by the First Amendment.

It has also ruled that members of the U.S. military “do not possess the same broad rights of expression that civilians enjoy.”

In fact there is a wider exception to the First Amendment, which is when it is “speech integral to criminal conduct.”

In the United States the First Amendment does not allow for those who make inflammatory remarks or encourage acts of terrorism to be prosecuted.

It said, “Proposals related to government action of this nature raise significant free speech questions, including the reach of the First Amendment’s protections when it comes to foreign nationals posting online content from abroad.”

The report said: “At the outset, it is not clear that a foreign national (i.e., a non-U.S. citizen or resident) could invoke the protections of the First Amendment in a specific U.S. prosecution or litigation involving online speech that the foreign national posted from abroad.”

“The Supreme Court has never directly opined on this question,” it added.

UK ‘Freedom of Expression’ Has Many Caveats

Article 10 of the 1998 Human Rights Act gave everyone the “right to freedom of expression.”But there are many exceptions, for example, “in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals ... for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.”

The 2006 Terrorism Act introduced a new offence of “encouragement of terrorism.”

As a result, statements which are “likely to be understood as a direct or indirect encouragement or other inducement to the commission of terrorist acts” can lead to prosecutions.

In 2019 Altaf Hussain, the exiled leader of one of Pakistan’s political parties, the MQM, was charged with encouraging terrorism over online speeches he had given from London to his supporters in Karachi.

He was acquitted in 2022 and remains in London.

Freedom of speech has traditionally been less protected under English law and it is also, arguably, less protected by culture or tradition.

Between 1988 and 1994 the British government forbade broadcasters from using the words of Sinn Fein spokesmen Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, and several other Irish republican and loyalist paramilitary leaders during The Troubles.

The BBC and other broadcasters found a way round this by using actors to dub speeches by Mr. Adams and others.

Then-Prime Minister John Major lifted the restrictions after the Provisional IRA’s first ceasefire.