News Analysis

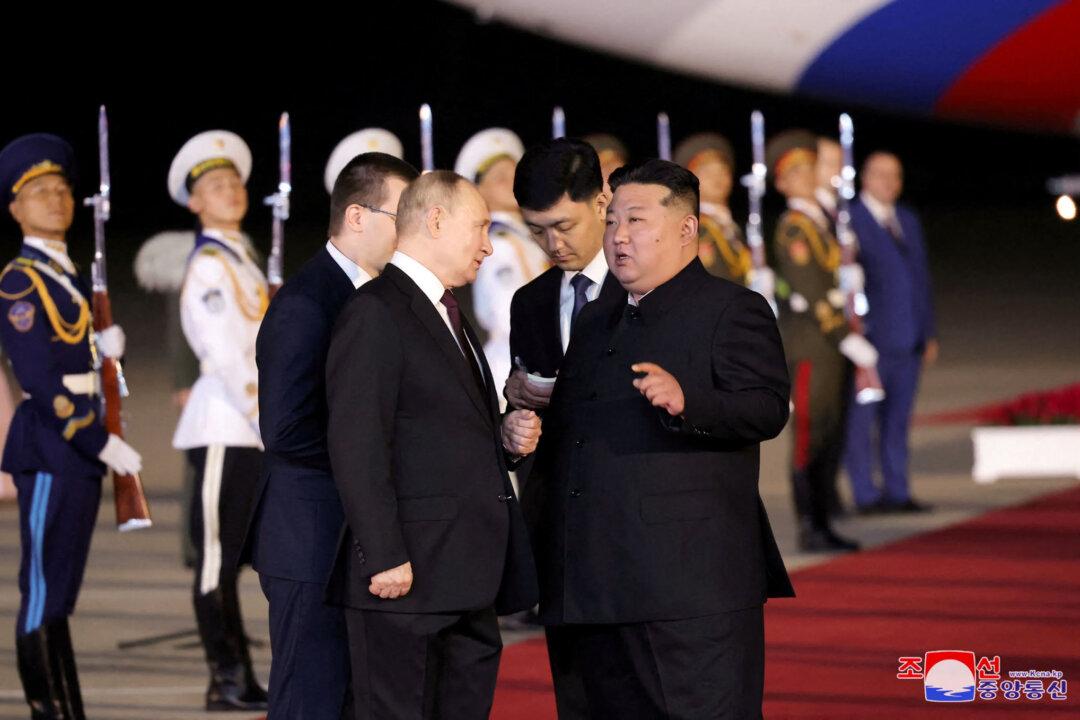

The foreign policy community is watching closely for signs that North Korean forces have joined the fighting in Ukraine, following the U.S. government’s announcement that it has seen signs that Pyongyang has sent troops to Russia.

The foreign policy community is watching closely for signs that North Korean forces have joined the fighting in Ukraine, following the U.S. government’s announcement that it has seen signs that Pyongyang has sent troops to Russia.