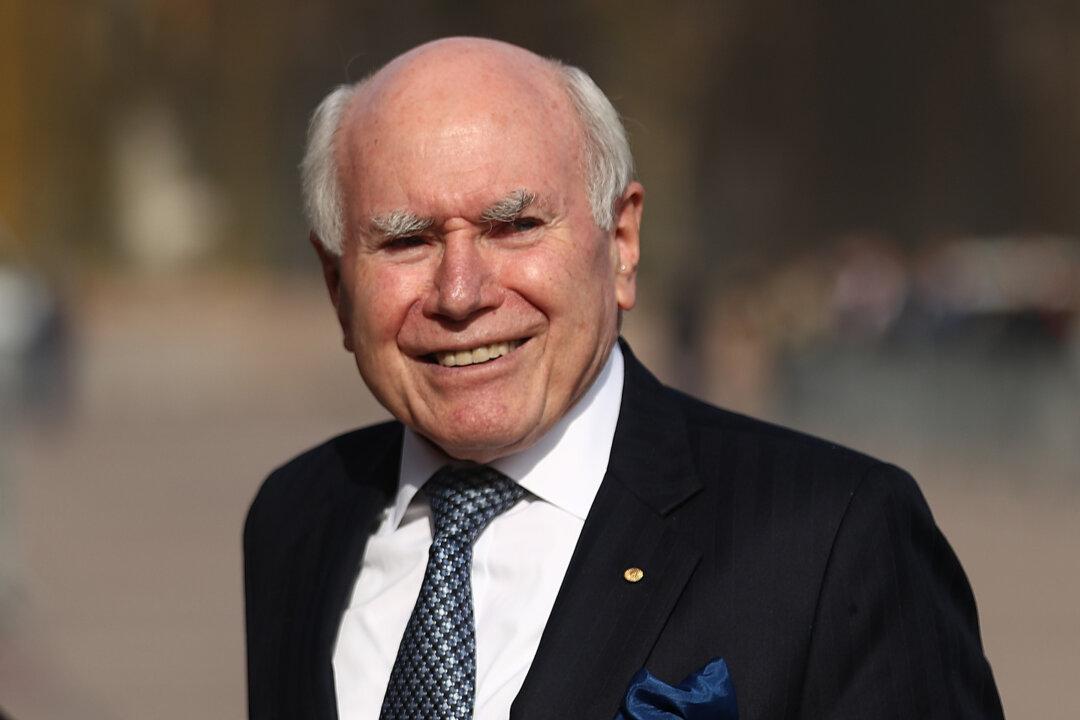

Indigenous advocacy groups should improve current policies rather than try to alter the Australian Constitution, says former Prime Minister John Howard.

“The question that the [Labor] government has to answer is why are they putting the millions of Australians who care about the future of Aboriginal people through the misery of an election campaign where they’re being asked to endorse something that hasn’t been explained?" he told ADH TV on Aug. 1.