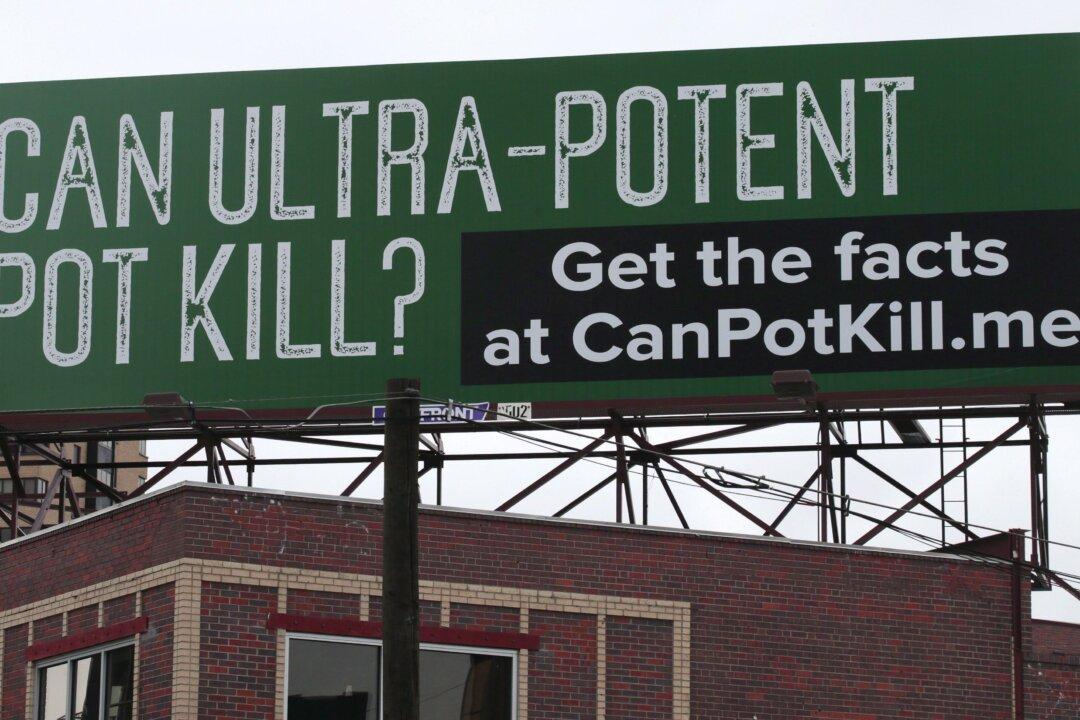

As legalization of recreational marijuana forges ahead in Canada, a U.S. law enforcement officer says making the drug legal is not such a good idea if Colorado is anything to go by.

Marijuana was legalized in Colorado in January 2014, and the consequences across the state have been negative with “no upside,” says Ernie Martinez, a command officer with the Denver Metro Police Department for 35 years and director-at-large for the National Narcotics Officers Associations Coalition.