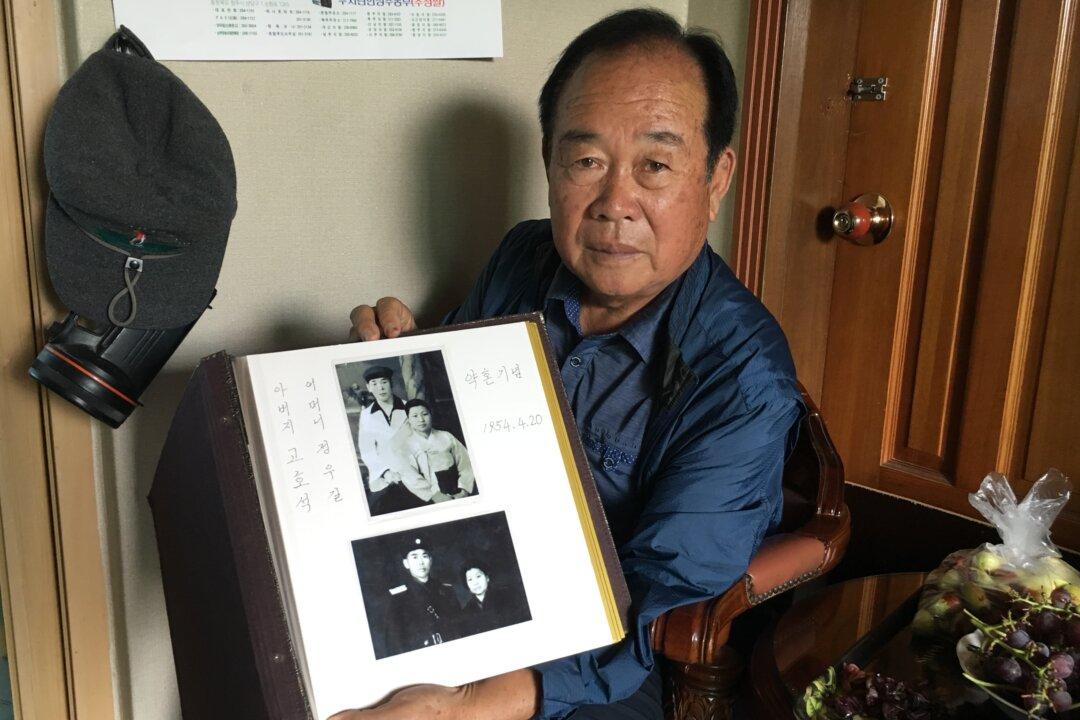

CHEONGJU, South Korea—The last time Koh Ho-jun saw his brother was six decades ago. Then 19 years old, his brother had high hopes for his future, wanting to pursue an education, but their family was poor and couldn’t afford it.

“North Koreans told him that he would be able to study however many years he wanted, and lead a wealthy life. That’s why he followed the North Koreans,” said Koh, 76, from his home in Cheongju in central South Korea.