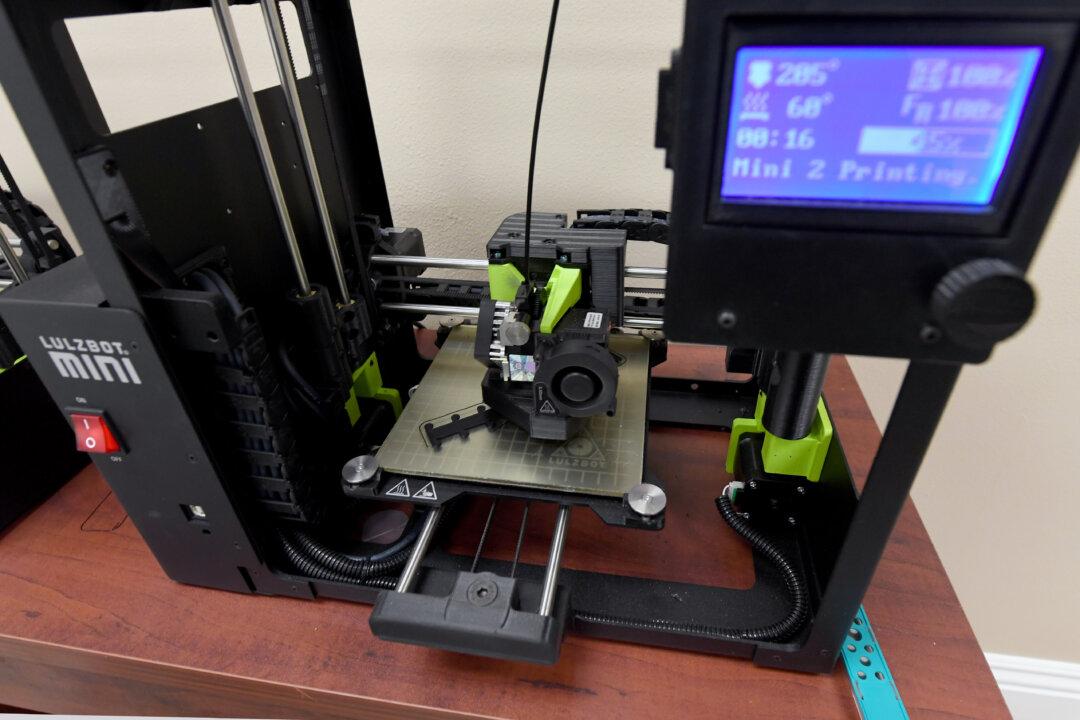

TORONTO—Groups of volunteers across Canada are using 3D printers to produce personal protective equipment (PPE) and other essential supplies at a breakneck speed—an effort some say could have a lasting impact even after the COVID−19 crisis passes.

These “makers” are volunteering their expertise, time, and tools to produce gear used on the front lines of the fight against the pandemic, drawing on open-source designs and creating their own.