Five countries pose the highest risk to Western travellers of being kidnapped by state agencies, a Senate inquiry into the wrongful detention of Australian citizens overseas has been told.

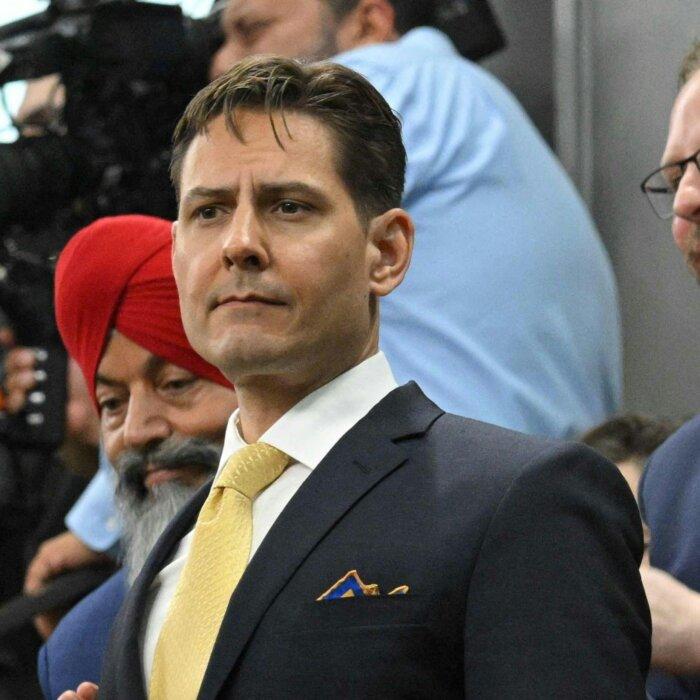

The United States special presidential envoy for hostage affairs (SPEHA) at the Department of State, Roger Carstens, told the Committee that China, Russia, Syria, Venezuela and Iran pose a high threat of committing “hostage diplomacy.”

Hostage diplomacy involves a foreign visitor being illegally detained and used for diplomatic leverage.

An indicator of the extent of the problem for the United States—and the priority placed on it by its government—is the fact that Secretary of State Antony Blinken carries a card featuring the names of every arbitrarily detained American around the world.

But the citizens of any Western ally, including Australia, are at risk, Ambassador Carstens emphasised.

As of July this year, 46 Americans were wrongfully detained or held hostage abroad.

The United States takes a very firm line on the issue.

“Our citizens are not human bargaining chips. They are not political pawns. If any country wrongfully holds any of our people, we will hold them accountable,” Blinken said recently.

But first, it carefully investigates the legitimacy of any arrest, even by a “high-risk” country.

“We’ve never revoked a wrong detention because new information has come to light [such as that] the person was guilty,” Carstens told the Committee.

“That’s why we put a lot of effort upfront because that’s what we fear. We fear if we take something to the secretary of state and he says, ‘This person’s wrongfully detained’ and ... suddenly we get more information, and you find out the person’s actually guilty of a bad crime like drug trafficking, murder, etc.”

“The system would actually not collapse or fall apart, but it would take a hit. And we don’t want the S\secretary to lose trust in the system. We don’t want the taxpayer or Congress to lose trust.”

US Forming Coalition

The United States is now focused on building an international coalition to oppose hostage-taking by foreign governments.“We’re not at the stage where it has a name,” Carstens explained, “But what we are doing right now is we’re working with countries that are suffering through the same problem, like Australia, to explore how we could work together and what tools we could use.” Finalising the alliance would take one to two years.

The tools would include diplomacy, economic and financial sanctions, legal efforts, intelligence and the military, he said.

“[Members of the alliance] can use elements of national power to increase the cost of someone being taken. So, as an example, let’s say that the Iranians take a Belgian citizen, and Belgium makes a case that this person is wrongfully detained.

“If we all agree, then all the countries in this multilateral group will start to come up with a strategy which can increase the price of this person being taken,” Carstens said.